As of early 2020, natural gas had never been cheaper. The situation looks set to continue as major gas producers fight for market share. The low prices have created a new wave of interest in gas-to-power generation, with some European analysts suggesting that they herald the ‘final closure’ of coal-fired generation on the continent.

Of the 22 African countries with proven gas reserves, 13 are currently consuming gas for power generation. But the outstanding part of the puzzle is liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is not yet imported by any country in the region. Current low prices are likely to play a part in shifting this pattern.

The centre of interest is Mozambique, where three LNG megaprojects have massive implications, not merely for the region but the global market. NJ Ayuk, a lawyer, author and executive chairperson of the African Energy Chamber, argues that the ‘self-actualisation’ of Mozambique’s gas potential has tremendous implications. ‘Just in foreign direct investment, Total’s US$25 billion amounts to more than two times Mozambique’s current GDP,’ he says. Ayuk, the author of Billions at Play: the Future of African Energy and Doing Deals, says the three megaprojects ‘alone could place the country among the five biggest LNG exporters in the world, up there with Qatar, Australia, Malaysia and the United States’. The three projects are set to deliver 30 million tons per year (mtpa) in the first phase of implementation. Compare that to the world’s biggest producer, Qatar, at 77 mtpa.

Plans are for Mozambique’s LNG to be exported mostly to the Far East. But the availability of LNG from a nearby source is expected to get other African countries – most notably South Africa and Kenya – interested in it.

The LNG import game in Africa is currently led by Ghana, which is building an import terminal with a floating and storage unit positioned alongside. Reports suggest the facility will become operational this year. Forty percent of Ghana’s energy requirements are already accounted for by gas.

Mozambique’s megaprojects are a response to the issue of how to develop gas finds in an underdeveloped part of the world. It is generally considered that it is not viable to pipe natural gas more than about 2 000 km to market. A project that breaks this rule of thumb, the proposed 4 400 km Nigeria-to-Spain Trans-Sahara pipeline, has struggled to get off the ground since being first mooted in 2009 and continues to be described by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation as ‘under consideration’.

Only South Africa offers a potential gas-using industrial agglomeration within anything like accessible distance, but it is a tiny market in the context of the scale of Mozambique’s resource. The solution is to super-chill the gas to liquid temperatures, transforming it into LNG, and to then transport it to market by ship. By this means, the global market has become accessible to Mozambique. The country’s megaprojects are looking largely positive. ‘ENI’s 3.4 mtpa floating Coral South facility is on schedule to come on-line in 2022,’ says Ayuk. This remains in line with the company’s own projections. The other two bigger, land-based projects, (ExxonMobil’s 15.2 mtpa Rovuma project and Total’s 12.9 mtpa Mozambique project) have longer time horizons, with Total anticipating production in 2024, and ExxonMobil in 2025.

A blip appeared in Mozambique’s steady development in October last year when ExxonMobil announced that the US$30 billion final investment decision (FID) for its 12.9 mtpa LNG train had been pushed out. A final decision had been expected, but only US$520 million in preliminary engineering contracts was announced.

No one has suggested that Mozambique’s gas-development programme is in any real danger, but ExxonMobil’s failure to clarify the delay has led to speculation that an Islamic insurgency in the gas-rich north of the country may be the problem.

Ayuk says ‘reports indicate that some of these insurgents come from extremely poor backgrounds and have been radicalised based on the idea that oil and gas companies are here to steal their resources, and that no one will benefit’.

He argues that it is imperative the government of Mozambique deals with the potential problem ‘not just by local content policies and employment opportunities but by educating [the population] about what is being developed, what to expect, and how this will affect and benefit them’. For Ayuk, the critical issue is ‘to combine strict transparency with resource-management policies’.

The other very large project is being developed by Total, which bought out early project developer Andarko for US$3.9 billion last year. It involves two initial land-based LNG trains with a capacity of 12.9 mtpa. A Total executive told a conference in Cape Town in November last year that the company had initiated a feasibility study for two further trains. An FID was announced by Andarko in June last year, which Total appeared to accept when it announced its acquisition of Andarko’s shareholding in September 2019. Total said the project had effectively been ‘de-risked’ because ‘90% of production is already sold through long-term contracts with key LNG buyers in Asia and Europe’.

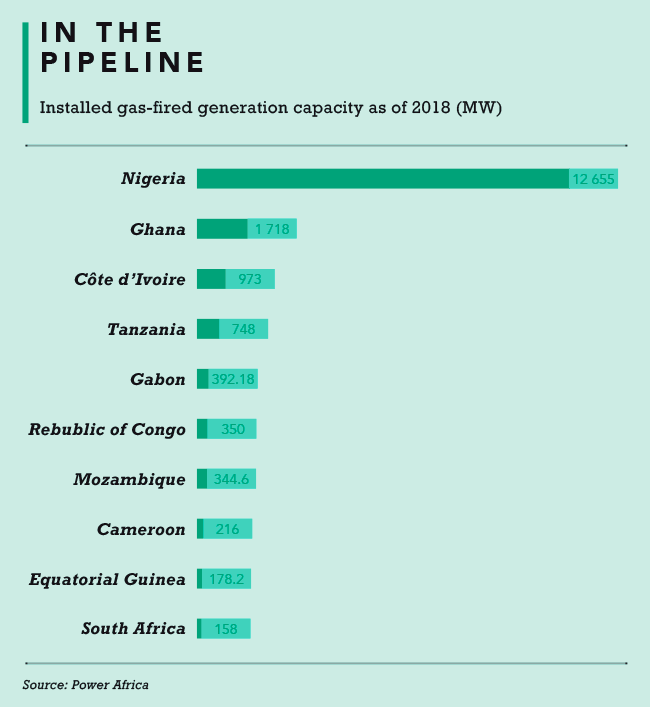

Gas-fired power stations are widely mooted as a critical element in Africa’s drive to reduce its energy backlog. Power Africa argues that existing gas-to-power plans can deliver an additional 16 000 MW of generation capacity to the continent by 2030.

However, as Prashaen Reddy, a principal at global management consulting firm Kearney, points out, ‘natural gas is regarded as a transition energy source to renewables’. He says that ‘carbon emissions from gas are 82% lower than coal’. Reddy argues that South Africa needs to consider shifting from coal to natural gas. ‘This makes environmental and business sense considering the financial repercussions for big emitters,’ he says. ‘The carbon tax introduced in South Africa last year uses the polluter-pays principle to force corporations to factor environmental considerations into their business decisions.’

Yet South Africa is behind the curve when it comes to introducing a gas economy. Adrian Strydom, acting CEO of the South African Oil and Gas Alliance, argues that the country has been dragging its feet when it comes to gas development. Despite plans to establish LNG import hubs at Richards Bay and Coega, near Port Elizabeth, gas is officially envisaged as playing a relatively small role in South Africa’s energy mix, mostly for peaking power plants that are currently powered by diesel.

According to the final draft of the country’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP2019), which was approved by Cabinet last year, just a further 3 000 MW of gas capacity is planned and that is to be added to the system only by 2024. This is a disappointment to gas advocates as it is a smaller allocation than the 8 100 MW in the draft IRP.

Reddy points out that any more extensive ambitions are constrained by government debt levels. ‘It’s up to independent power producers and investors to take the lead in kick-starting our gas sector,’ he says. Reddy argues that ‘to move away from a reliance on coal, we need public-private co-operation and a collective shift in mindset about the role of gas in this transition’.

Strydom says it’s a ‘no-brainer that South African firms should get involved in the Mozambique gas industry’. He suggests that ‘it would be unwise for South Africa not to use LNG, given the potential of Mozambique’s industry to supply this’. He adds that ‘gas is new to us in South Africa, but experience in Mozambique will stand us in good stead when it comes to developing the industry locally’.

This may happen sooner than expected. Earlier this year, prompted by unanticipated national electricity outages, South Africa’s Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, Gwede Mantashe, published a request for information from companies able to implement significant electricity-generation projects in the next 18 to 36 months. Among the proposals received was one from Mhlathuze Energy for a 300 MW combined-cycle gas-generating plant (with potential modular additions expanding it to 1 200 MW) located at Richards Bay and based on imported LNG.

There are several established firms behind the proposal, including a Japanese multinational and local BEE company Phinda Power. A positive response from the minister would substantially shift the prospects for gas in South Africa.