That South Africa is a water-scarce country is a fact. Government’s 2022 National Development Plan acknowledges that demand for water in South Africa will exceed the available supply ‘at the planned level of assurance’ by between 1.6 billion and 2.7 billion m3 by 2030, with seven of the country’s 13 major water systems predicted to be in deficit by 2040.

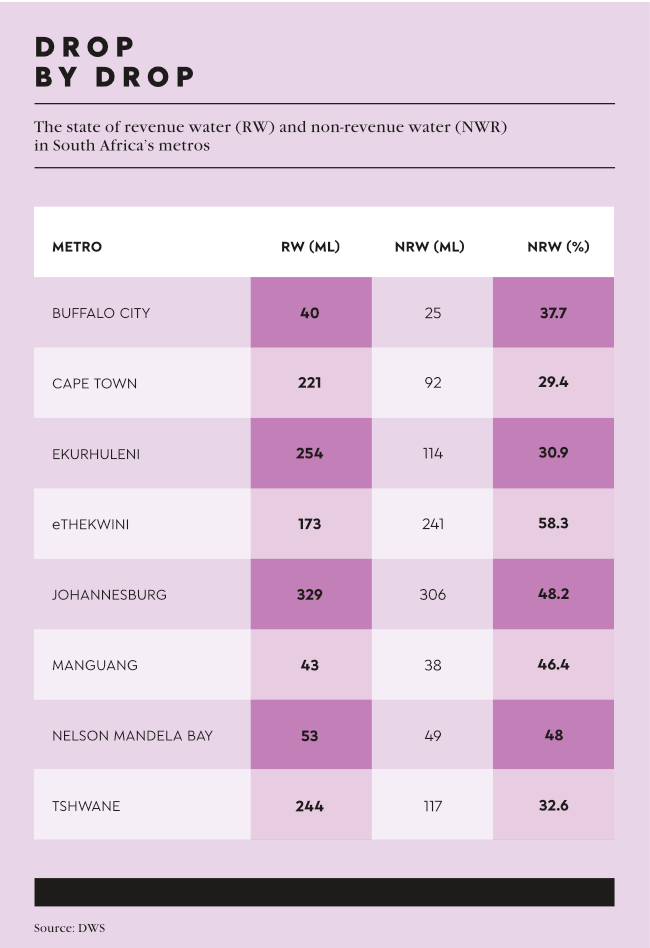

Despite this precarious position, almost half the water that is purified in the country ends up going down the drain without ever being used. The Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation’s (DWS) most recent No Drop report puts national non-revenue water (NRW) at 47.4%, 40.8% of it through pipe leaks.

At a municipal level, the situation becomes more alarming. In Durban, for example, NRW is estimated at 58% and in Johannesburg it’s 48.2%. It’s not surprising that it’s these two municipalities that have made recent headlines – local and international – because of their water shortages.

The country’s NRW losses mean that half the water that is purified cannot be charged for, resulting in dwindling revenue for municipalities – meaning there is less money to reinvest in maintaining ageing infrastructure, which perpetuates the cycle. According to the Daily Maverick newspaper, when taking the municipality’s surcharge on water into account, NRW losses in Durban equate to ZAR7.6 billion a year in revenue – more than 10% of its total budget for 2024/25.

Kate Stubbs, marketing director at waste-management solutions provider Interwaste, points out that for Johannesburg, the country’s commercial capital, the impact of water outages has been far worse than residents lacking bath water.

‘Businesses in water-reliant industries such as restaurants, gyms, car washes and construction, among others, have also been severely impacted. The lack of water supply has led to businesses going for hours and sometimes days without water and operating for fewer hours – generating less income and creating a knock-on effect in terms of letting staff go, compromised hygiene and increased health risk,’ she says.

The solution seems obvious… Fix the water leaks. ‘It’s high time for the Department of Water and Sanitation [DWS] to say to municipalities if you want more water, fix the leaks first,’ Jay Bhagwan, senior manager of the Water Research Commission, told Daily Maverick. ‘The cup is only so big. It is not acceptable if you continue along this trajectory of providing more water to service municipal leaks. It costs much more to build new dams compared with fixing leaks.’

Government messaging seems to support the fix-it approach. DWS director-general Sean Phillips indicated in December that government assigned municipalities more than ZAR20 billion in infrastructure grants for water and sanitation services every year.

He has urged municipalities to use the grants to reduce NRW by ‘buying meters to detect where the losses are’ and to replace ageing pipes.

A month later, DWS Deputy Minister David Mahlobo urged municipalities to re-invest money collected from revenue into water and sanitation services to ensure sustainability of infrastructure that will stand the test of time.

‘Operation and maintenance, and renewal of water and sanitation infrastructure, is of critical importance, and we need to invest in this consistently. Part of the money that people pay for services needs to be used for maintaining the existing infrastructure so that we don’t experience problems in the long run,’ he said.

Parliament is expected to approve the Water Services Amendment Bill this year, which will ringfence municipal revenue from water and sanitation so that it is channelled towards maintaining and upgrading water infrastructure and funding partnerships with the private sector.

According to DWS Minister Senzo Mchunu, the legislative changes will see municipalities having to appoint water service providers whose operating licences will depend on their ongoing performance. In addition, Mchunu said he expected Parliament to approve the National Water Resources Infrastructure Agency to oversee major water projects.

Writing in the Conversation, Craig Sheridan, director of the Centre in Water Research and Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, attributes Johannesburg’s water woes in part to the eight-year delay in the latest phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water project, which is now coming online only in 2028.

‘In 2023 the province [Gauteng] had the same amount of water storage for a population that had grown by over 3 million people (or 25%), because the dam was not built,’ he writes. Furthermore, Johannesburg’s ‘maintenance needs are spiralling out of control. The city bills residents for rates, water, electricity, sewage and other services. However, the funds received are not ringfenced. Other projects are competing for the same pot of money’.

Sheridan acknowledges that municipalities do need ‘to focus on non-revenue water, by allocating the correct and appropriate maintenance spend to fix and even renew the water network’.

Yet getting municipalities to reinvest in water infrastructure is only one part of the solution. ‘At the same time, citizens need to seriously consider their own water usage and how to reduce it,’ he says.

He points out that average water consumption in Gauteng is too high. At 279 litres per person per day it has the highest water use of the nine provinces – 27% higher than the country average.

Like Sheridan, Stubbs emphasises that ‘while fixing the leaks and creating sustainable infrastructure is critical’ in ensuring sustainable access to safe water, it’s going to take much more than that. It’s more about examining a circular economy approach and examining much more diverse water mix, including groundwater and water reuse. ‘Not many know that all effluent water can actually be recycled and, when done properly, can create a strong solution for water sustainability and access – water that was previously not deemed safe for consumption. This means a large bank of water could become available for redistribution into the environment for irrigation and dust suppression, as well as to replenish rivers and catchments in our water infrastructure networks.’

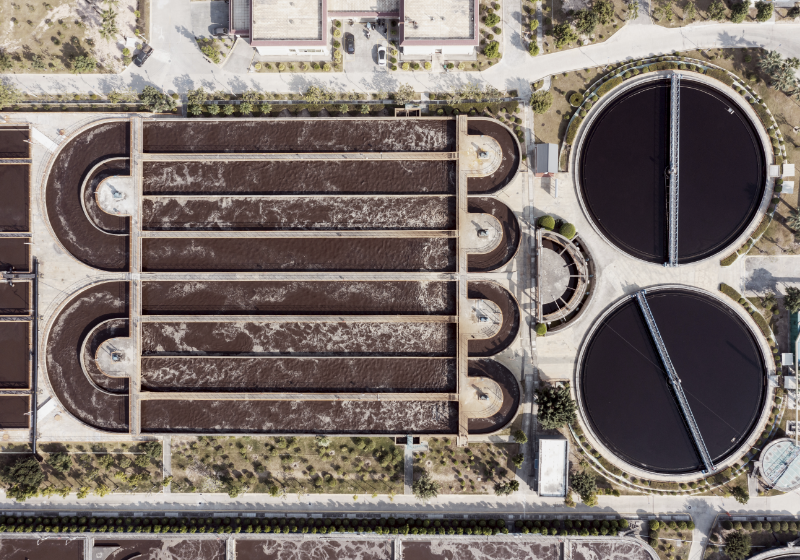

She points out that some waste companies are already using various technologies to treat and process effluent streams to a level where they can be recycled and reused for various purposes. In April 2024, Interwaste launched its leachate and effluent treatment plant in Delmas, Mpumalanga. The plant, which Stubbs describes as the ‘first environmentally responsible waste treatment facility in South Africa’, can treat about 43 million litres of water per year – recovering 80% to 90% of it into clean water.

For those put off by the ‘yuck’ factor in reusing water, it bears reminding that Namibia has been successfully retreating effluent water into potable water for more than half a century. In 1960, its Goreangab water reclamation plant became the first in the world to produce purified drinking water directly from sewage water.

Today, the plant – replaced by a newer version in 2002 – produces up to 25 000 kilolitres of drinking water every day, about 35% of water needs in the capital, Windhoek. Standing as an example to the rest of the world, the plant has never been linked to any water-borne diseases.

Other simpler technologies exist to help municipalities better manage water supply. For example, Craig Barbeito, group control valve specialist at AVK Southern Africa, says the company has started to supply its day/night pressure-reducing 869 control valve, launched last July, in Malawi.

The valve enables water networks to set the pressure higher during peak hours while reducing it off-peak, he explains. ‘These various functions help to protect equipment and pipelines by managing water levels, controlling pressures and controlling flow rates. These are all critical aspects of water supply and demand.’

Improving access to safe water supply in South Africa is obviously not a simple task. The country will have to find ways for the public and private sectors to unilaterally work together to ensure plans are viable and cost effective while understanding that this requires cross-functional collaboration, long-term planning and implementation to create a sustainable solution.