In December 2023 Stanford University, the Hoover Institution and the Rock Centre for Corporate Governance published the results of a survey of 933 US investors. It found that among millennials and Gen Zers – the supposedly socially conscious cohort aged 18 to 41 – preference for ESG investing has plummeted.

Young investors who said they were ‘very concerned about environmental issues’ dropped from 70% in 2022 to 49% in 2023. ‘More investors are unwilling to personally bear the risk of advancing environmental and social change,’ wrote study co-author David Larcker. ‘They might want conditions around them to change, but they don’t want it to come out of their pocket.’

Meanwhile, on the far side of the world, the 28th session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was concluding in Dubai. The summit – better known as COP28 – ended on much the same note, at least from an African perspective. Delegates wanted to fix the world but weren’t so keen on paying the repair bill.

Dubai at first seemed a controversial venue for the world’s biggest climate conference. Indeed, leaked documents that surfaced just before the event alleged that the Emirati delegation planned to use the summit as an opportunity to strike oil and gas deals.

Yet somehow, success happened. COP28 concluded with government ministers from nearly 200 countries agreeing to ‘transition away’ from the biggest cause of climate change – the burning of fossil fuels.

‘We delivered world first after world first,’ the UAE summit presidency announced on social media. ‘A global goal to triple renewables and double energy efficiency. Declarations on agriculture, food and health. More oil and gas companies stepping up for the first time on methane and emissions. And we have language on fossil fuels in our final agreement.’

The statement glossed over the fact that the first draft of the agreement had completely omitted any mention of the phasing out of fossil fuels. But after 28 COPs, African delegates have come to expect dramatic reversals, last-minute deals and a lingering sense of these events combining big disappointments with even bigger promises.

Sydney Chisi, executive director at Reyna Trust in Zimbabwe, summed up the former in an interview with Sputnik Africa. ‘If you look at COP28, this time around [there were] actually way more oil lobbyists present,’ he said, adding that – judging by the behaviour of the OPEC countries that were refusing to phase out fossil fuels and almost winning that debate – it shows that poor African countries will never have strong negotiation power against those that have money.

A more balanced way of looking at it would be to accept that climate action requires investment; and, for now, the global appetite for climate action simply isn’t matched by a desire to fund it. And that puts climate finance at the centre of Africa’s post-COP28 conversation.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Africa accounts for one-fifth of the global population, yet it attracts just 3% of global energy investment. ‘By 2030, energy investment needs to double to over US$200 billion per year in order for African countries to achieve all their energy-related development goals, including universal access to modern energy while meeting in time and in full their nationally determined contributions,’ it notes in a recent report.

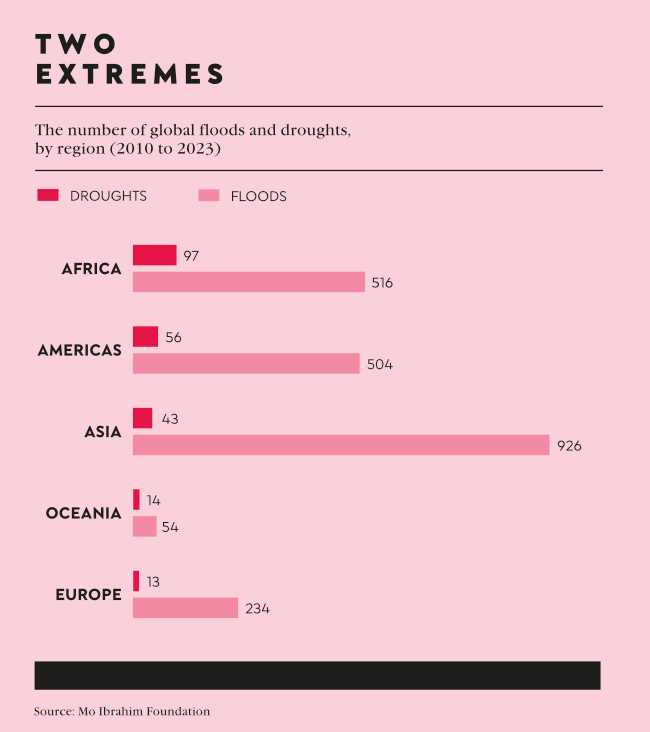

The sense of injustice is deepened by the fact – as reported by CDP Worldwide, among many others – that Africa accounts for the smallest share of global greenhouse gas emissions. The continent’s share is just 3.8%, compared to 23% in China, 19% in the US, and 13% in the EU. Yet while Africa is one of the smallest contributors to climate change, its people are among the most affected – as the continent’s catalogue of climate-related disasters confirms.

To that end, one of the most significant outcomes of COP28 was the official launch of a Loss and Damage Fund, which will help vulnerable countries deal with the impacts of extreme weather events brought about by climate change. The fund, which has been more than 30 years in the making, will rely on donor government contributions and will be run by the World Bank. At COP28 it was seeded with US$700 million in donations, mostly from developed countries. It’s a start, but it represents just 0.2% of the estimated losses developing countries face from global heating every year. Cyclones Kenneth and Idai alone caused about US$2 billion in loss and damage when they battered Mozambique in 2019.

And fixing the damage is only one side of the challenge. Climate financing is the other side of it, and that’s where much of the work will need to be done as we head into COP29 in November 2024. Take the much-lauded agreement to transition away from fossil fuels, for example. ‘The text calls for a transition away from fossil fuels in this critical decade, but the transition is not funded or fair,’ Mohamed Adow of the NGO Power Shift Africa told Radio France Internationale. ‘We’re still missing enough finance to help developing countries decarbonise, and there needs to be greater expectation on rich fossil fuel producers to phase out first. Finance is where the whole energy transition plan will stand or fall.’

COP28 saw more than US$85 billion in commitments, in one form or another. And as Romy Chevalier and Alex Benkenstein, both of the South African Institute of International Affairs, told the Council on Foreign Relations, ‘more of this financing will go toward adaptation, which Africa and other developing regions have advocated for several years. Indeed, a key priority on Africa’s climate agenda was agreement on the adaptation targets for the Global Goal on Adaptation [GGA]. The COP28 agreement calls for concrete planning and implementation of adaptation efforts by 2030, as well as significantly increased adaptation financing, yet the agreement does not include specific goals on adaptation finance’.

The GGA was another landmark outcome of COP28. First proposed by the African Group of Negotiators in 2013, it was established (without being defined) as part of the Paris Agreement in 2015 and launched at COP26 in 2021. At COP28, it finally got the go-ahead.

But in its execution, the GGA puts Africa on the sidelines of a climate change agenda that is central to the continent’s development – as Brian Mantlana, a commissioner on South Africa’s Presidential Climate Change Commission, writes on the African Arguments online news platform. ‘The heart of the GGA is supposed to be about ensuring effective participation by all countries to achieve agreed objectives on adaptation,’ he says. ‘As such, the African Group of Negotiators [AGN] has consistently called for direct linkages between targets and provision of support – financial, capacity building and technology transfer – for implementation.’

Mantlana does not interpret this as a call for a new dedicated fund. Between the Loss and Damage Fund, Adaptation Fund, Least Developed Countries Fund, Special Climate Change Fund and the Green Climate Fund, there are already at least five funds that aim to address adaptation-related issues. ‘Rather, I understand African negotiations’ position as asking to be more than mere participants in shaping global adaptation policy and having more than just “a seat at the table”; recognising that the GGA process requires empirical data and not just anecdotal information, and acknowledging that African countries lack the financial and institutional capacity to collate such empirical data; and seeking assurances that industrialised countries will ensure African contexts inform this critical global adaptation discourse,’ he writes.

The AGN, adds Mantlana, did not receive these assurances at COP28.

Yet not everybody shared his disappointment. The South African government welcomed what it called the ‘landmark decision’ to adopt the GGA, with Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment Barbara Creecy calling it ‘a big step forward’.

That’s the lingering sense for Africa after COP28 – there were a few big steps forward, but questions remain over how Africa will transition to a new climate secure future… And who’ll pay for it.