When hand-washing became a central part of the COVID-19 hygiene protocols, a Pretoria-based intelligent-metering firm came up with a smart device to remotely monitor the levels in water tanks. In July last year, Lesira-Teq presented its Jojo tank level monitor to two of the busiest areas in Polokwane, Limpopo – the Sechogo and City Centre taxi ranks – to ensure commuters had sufficient water to wash their hands to prevent the spread of the virus.

‘Water tanks are crucial in delivering water to areas that need it, especially during the pandemic,’ according to the company. ‘The tanks need to constantly have water so that communities do not struggle. That is why we have created a device that notifies the authorities via SMS or the Lesira app whenever the tank has reached maximum water capacity, is running low, or completely empty.’ The small device, which has a 10-year battery life and is installed inside the tank, also sends an alert if someone tries to steal or vandalise the tank, or opens the lid without authorisation. The alerts and status updates are transmitted by internet of things (IoT) technology via low-power wide-area networks (LPWAN), which are less prone to interruption in the event of a power failure than the GSM (mobile phone) network.

In Africa, LPWANs such as Sigfox, LoRa and Narrowband IoT (NB-IOT) are increasingly being used by utilities (and as the preferred networks for building smart cities) because of their low cost, high reliability and far-reaching coverage. Solutions for remote water-status level monitoring, including the Jojo tank level meter, could improve the precarious water supply in communities that don’t have access to the municipal water grid – provided the municipality responds to the alerts by promptly refilling the tanks.

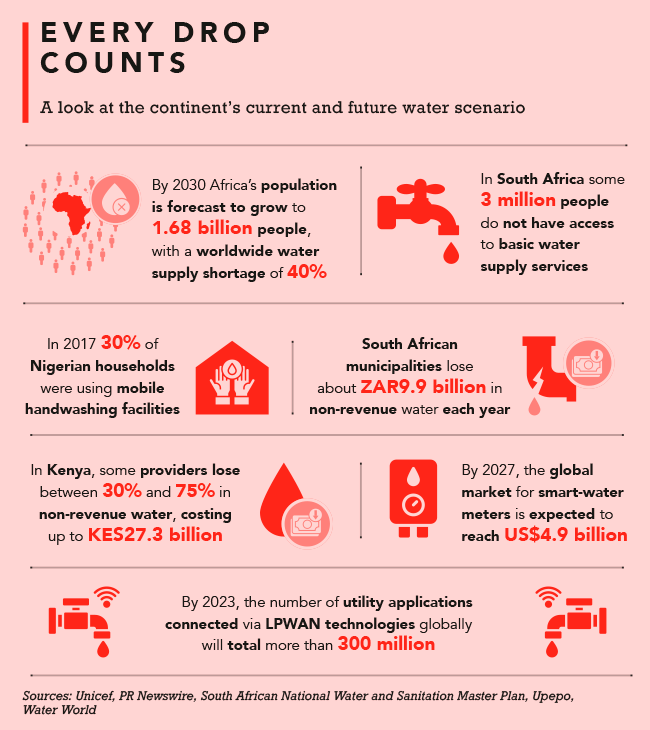

Africa is already experiencing a water crisis. A combination of inefficient water management, lack of investment and extreme weather events such as droughts and floods, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, are slowing the continent’s progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goal 6 – ‘clean water and sanitation for all’. Just 59% of Kenya’s population has access to basic drinking water services, according to Unicef, compared to 64% of South Africans and 70% of Nigerians. However, a recent report by Unicef and Nigeria’s Ministry of Water Resources puts this figure into perspective by stating that Nigerians receive only nine litres of clean water per day on average (well below the minimum acceptable range of between 12 to 16 litres per day). COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of decent water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services as a fundamental human right.

In addition to these challenges and those relating to limited and ageing water infrastructure, Africa’s municipalities lose significant income through non-revenue water. This is water that has been treated and pumped through the mains, but doesn’t reach the customer and is not paid for – due to real losses (such as leaks and burst pipes) and apparent losses (including billing errors, faulty meters, theft or illegal connections).

‘Non-revenue water is a problem globally but more prevalent in developing countries where aged infrastructure and socio-economic issues compound the problem,’ says Chetan Mistry, strategy and marketing manager at Xylem Water Solutions South Africa, a company firmly rooted in smart tech. He adds that the loss of revenue is ‘a massive issue because it shrinks the investment available to upgrade water systems towards optimised and efficient systems’. In Kenya, water utilities collectively lose 52% of their water this way, according to the Water Services Regulatory Board. In South Africa, 41% of municipal water doesn’t generate any revenue, with leaks accounting for 35% of losses. This adds up to 1 600 million litres per year in non-revenue water, according to the South African Water and Sanitation Master Plan.

Water authorities in Africa are increasingly resorting to technology to address these challenges and improve sustainability – their own as well as that of the scarce natural resource at the core of their operations. While a simple water-meter strategy can assess systems at checkpoints to improve detection and repairs, and reduce water losses, leak-detection systems based on smart tech can have a more far-reaching impact. ‘Xylem’s Sahara and SmartBall technologies use acoustic, gyroscopic, video and a multitude of sensing systems to adopt reactive and proactive preventative strategies,’ says Mistry. ‘These systems can pinpoint leaks and assess kilometres of pipes, ensuring the system is kept in prime condition for optimal performance.’

South African firm Conlog is another company with a key focus on water-loss reduction. It provides smart electricity-metering solutions worldwide, with 70% of its business in sub-Saharan Africa and manufacturing plants in Dube TradePort, South Africa and Ikeja, Nigeria. Preparations are under way to expand the business to include water-demand management and manufacture the first smart-water product in Q1/2022.

‘The vending technology is the same for both electricity and water meters,‘ says Desigan Govender, product manager at Conlog, who adds that the company’s smart water-demand management product could be used for anything from prepaid water, remote meter reading and consumption monitoring to leak detection and flow limitation. ‘The technology lends itself to different scenarios as it will be an adaptable platform that can address many issues faced by municipalities,’ he says. ‘We like the concept of using the same device across the board and only changing the way it’s set up, because it hands the power to the municipality.’

As most municipalities and water utilities already have existing infrastructure and billing platforms that they generally can’t afford to replace from scratch, any new technology needs to be able to integrate as seamlessly as possible. Inzalo Utility Systems, a smart-metering company that has been involved in projects in 26 countries worldwide – with a focus on the SADC region, where it has a foothold in Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe – says its solutions employ an open-architecture system and can be used with a variety of meters and housings to suit market-specific requirements.

‘Our smart technology is a non-proprietary and very flexible end-to-end solution, which can integrate with any water meter across the globe, as long as it has a pulse output,’ according to Sbonelo Mazibuko, CEO of Inzalo Utility Systems. The company has already supplied more than 1.3 million water-management devices to 50 municipalities in South Africa, including Johannesburg, eThekwini, Mangaung and Cape Town, where the devices were installed during the ‘Day Zero’ drought to throttle the water supply in high-use households that were exceeding their daily water allocation.

‘Pre-drought, these devices were exclusively being rolled out to low-income households that had very high arrears and water debt, usually as a result of a leak on the property,’ says Gina Ziervogel, associate professor of geography at the University of Cape Town and research chair for the African Climate and Development Initiative. ‘But during the drought, water-management devices were put into all households with high water use, regardless whether they had the money to pay their water bill. I think this was useful in getting wealthy residents to understand that they couldn’t buy their way out of the water crisis. The only course of action was for everybody to cut down on water use.’

Tech, therefore, can play a vital role in saving water – not only at utility level but also by encouraging behavioural change among consumers. The latest generation of IoT-enabled water-management products enables consumers to access information about their consumption via a mobile app on their smartphone.

‘It’s both a monitoring and management device, placing the power of consumption in the hands of the end user,’ says Edwin Sibiya, CEO of Lesira-Teq about his company’s smart-water meter. ‘They can track their water consumption daily or monthly on our customer smartphone application and make better decisions about how water is used in their household.’ This means that consumers have control over their water spend, as well as being able to react in real-time if the app indicates a leak or burst pipe on their property.

Inzalo Utility Systems’ latest solution combines the basics of prepaid-water metering with flow-limitation controls and water-loss prevention tools. Called AquaFlow, it’s an IoT-enabled water-management device that can transmit data wirelessly to municipalities or water-service provider databases and receive commands remotely. ‘Being able to instruct the AquaFlow to open, close or restrict flow of water remotely is a highly innovative leap forward for municipalities,’ says Mazibuko.

He explains that this is useful for flow limitation to ensure that indigent consumers receive their daily free allocation of water. If they require additional water, the device allows this to be purchased on a prepaid basis. Water tokens – like the 20-digit ones for pre-paid electricity – can be bought through the app, website or participating retailers. For post-paid customers, AquaFlow accurately automates the readings and invoice generation. Technology has significantly improved the transparency, accuracy and efficiency of water utilities and municipalities in Africa.

The availability of data on water-consumption patterns is enabling better customer service, billing and revenue collection, while also making it easier to reduce water being wasted through leaks, theft or careless behaviour. ‘It’s not only about throwing IoT technology into the mix but also about combining all available technology into a well-designed system, with key goals at the heart of its intention,’ says Xylem’s Mistry. ‘Having the right strategy in modernisation is key to ensuring the adopted technologies have a meaningful impact and bring about specific objectives.’