If everything goes well, South Africa will finally have a modern, transparent online mining cadastre, just like its neighbours Botswana, Namibia and Mozambique.

In fact, nearly all African countries with mining interests are by now using such an electronic system – from Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, the DRC, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya, Libya, Malawi, Mauritania and Nigeria to Zambia. However, the inadequate South African Mineral Resources Administration System (SAMRAD) still relies on paper-based documents and doesn’t operate outside office hours.

After years of delays and missed deadlines, the country’s Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) has now begun the process of procuring an off-the-shelf v that can be customised to South Africa’s needs. In March 2023, the DMRE and the State Information Technology Agency issued a request for bids for the long-overdue online cadastre.

‘This could be a massive game-changer for the mining industry,’ says Allan Seccombe, head of communications at the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA). ‘We are hopeful it will meet our long-standing request to replace the dysfunctional and opaque SAMRAD system with a transparent, off-the-shelf, proven cadastral system that will speed up the processing of prospecting and mining right applications, to make South Africa globally competitive and attract investment in the exploration, development and mining of the country’s minerals.’

A mining cadastre is an online portal for processing applications for mining rights, exploration permits and mineral processing licences in real-time.

It maps the country’s mineral resources in a way that the public can see who has applied for which mining rights, when they expire, and where they are located, among others.

In addition to streamlining and speeding up the management of mining applications, and safeguarding it against queue jumping and tampering, the online cadastre also serves as an entry point for junior miners and renewable-energy providers. By making geological data publicly available in real-time and at no cost, the system shows which pockets of land are still available – thereby attracting investment and helping juniors with limited exploration budget.

Just before the DMRE published its request for bids, consultancy AmaranthCX released what it believes to be the first effort in South Africa to publish an electronic all-commodity map. The comprehensive map contains geospatial information collated from mainly public sources, such as disclosure requirements from JSE-listed mining companies, publicly available environmental impact assessment documents, court proceeding, and from records published by the South African Heritage Resources Agency.

AmaranthCX’s paid-for map has the potential to bridge the geospatial gap until the proposed government cadastre becomes operational. This will take a while, because even an off-the-shelf system will take months to procure, followed by the installation of the necessary software and computer infrastructure, as well as the training and staffing, before the backlog within the system can be sorted out.

‘It beggars belief it’s taken this long for South Africa to start the procurement process,’ says Peter Leon, partner and Africa chair at law firm Herbert Smith Freehills. ‘These cadastral systems have been rolled out all over Africa for the past 10 years, often with funding from the World Bank.

‘Having a virtual system that is open and automated reduces potential opportunities for malfeasance and corruption, because everybody can see the applicants in the queue, which rights have been granted to whom and which are still available.’ Not having such a system has already led to major litigation in South Africa, says Leon.

He worked on a prominent mining case just more than a decade ago that centred around prospecting rights for the Sishen iron ore mine and involved fraudulent applications and collusion with local DMRE officials. ‘This kind of thing will continue to happen when you have a paper-based system that is not automated and transparent,’ he says.

The council had even offered to pay towards a new cadastre, because the application backlog is so costly. In December 2020, a survey revealed that member companies had exploration and mining projects worth about ZAR20 billion that were prevented from being developed as a result of delays in the approval of permits and mining rights transfers.

However, the MCSA is encouraged by the success of cadastre systems in other African countries.

‘Botswana is the most highly regarded destination in terms of mining regulations for the African continent,’ says Seccombe. ‘It’s very efficient, taking just 20 days to award a prospecting right. Internationally, the benchmark is about six months for the issuance of a mining right. In South Africa, this runs to about a year or more.’

He adds that ‘the last information we have on the backlog of mining and prospecting rights in South Africa came from a presentation to the portfolio committee in Parliament’. According to this, the backlog measured 2 625 applications for mining permits, mining right and permit rights in November 2022, which is 43.5% less than the previous backlog period (4 647 unprocessed applications in March 2021).

Athi Jara, a director at Werksmans Attorneys, explains why it’s so important from a legal perspective to get to grips with this backlog and have an effective mining titles registration system to manage South Africa’s mineral wealth. ‘As the custodian of the country’s mineral resources, the state is tasked with granting, issuing, refusing, administering and managing mining titles,’ she says.

‘Section 5(1) of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act makes it clear that a prospecting right or mining right registered in terms of the Mining Titles Registration Act is a “limited real right” in respect of the mineral and land to which such right relates. What this means is that on registration of a right, no third party may have a claim to the mineral in question and that a holder has a secure right that is enforceable against the world.’

This provides for security of tenure for the holder for the duration of the mining title – and, according to Jara, it’s this security that is paramount to mining companies and local and international investors.

Leon agrees that an online cadastre system will boost security of tenure by rooting out overlapping applications and rights – cases where the DMRE has mistakenly granted the rights over the same property to different companies.

‘Security of tenure is absolutely critical for mining companies,’ he says. ‘Mining is a long-term, capital-intensive business with lead times of 10 to 20 years from discovery to production. For that reason, mining rights are granted to up to 30 years. The future of our mining sector, and the 450 000 jobs it supports, is at stake, as the government has failed to address the fundamental issues affecting the industry’s growth.’

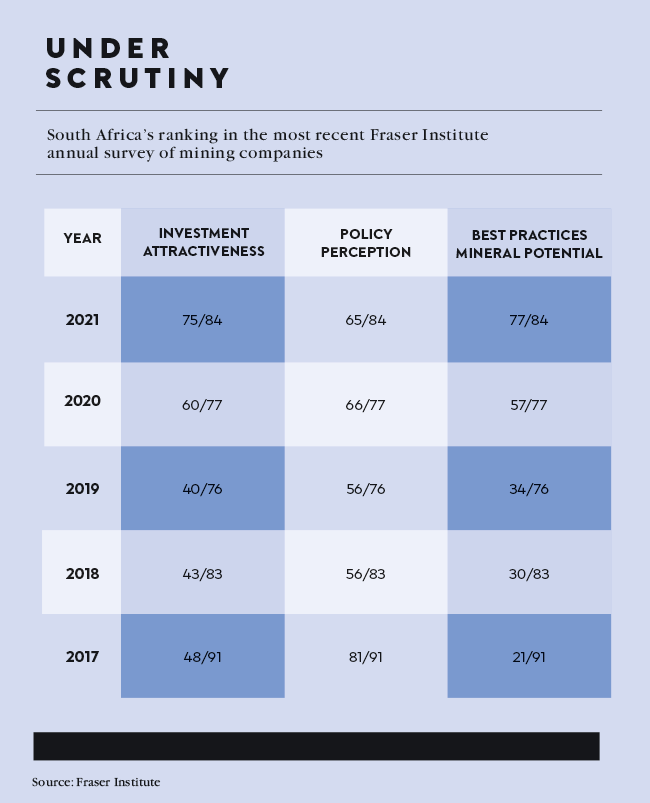

A functioning online cadastre will also go a long way towards reaffirming the investor confidence that has been lost in the past years. Notably, the Fraser Institute Investment Attractiveness Index, which saw South Africa falling to 75th place out of 84 countries (down from 40 in 2019) and ranking 12th out of 15 countries in Africa. Having vast mineral wealth is clearly not enough when a jurisdiction is lacking regulatory certainty and a transparent, efficient mineral licensing system. Therefore, the new electronic cadastre promises to improve the situation dramatically. ‘Like everyone else, we’re waiting,’ says Seccombe. ‘Fingers crossed.’