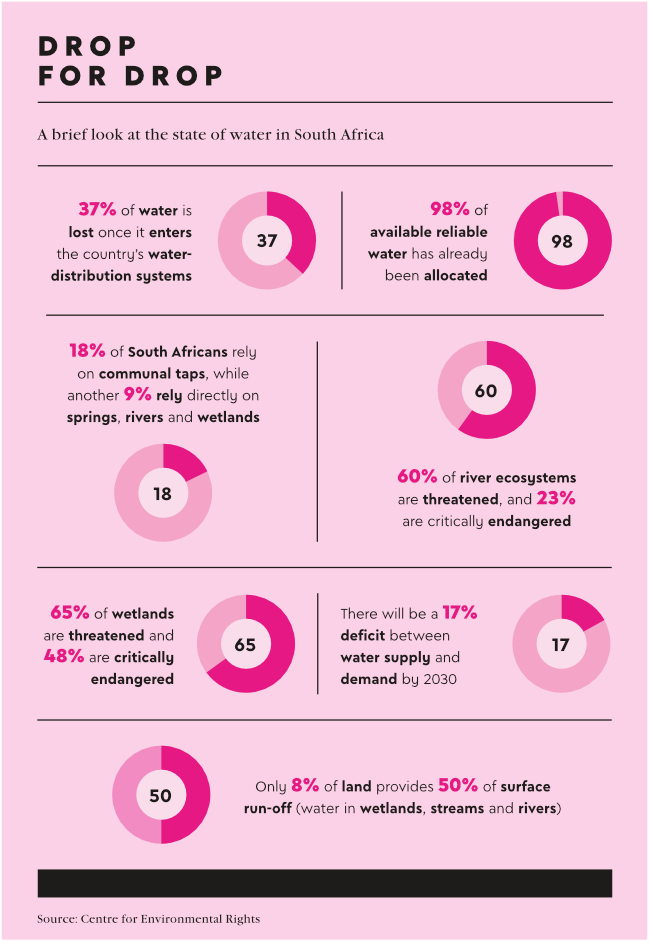

Water is precious and becoming ever more valuable. Ninety-eight percent of all the available water in South Africa has already been allocated, according to the National Water Source Strategy study, and by 2030 the country is expected to have a 17% deficit between supply and demand. Therefore, unambiguous and robust legislation is crucial to ensure that there will be sufficient water of adequate quality available for the various competing users.

Worldwide, business leaders are starting to understand the serious financial impact of water scarcity on their operations. According to estimates by the CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project), some US$301 billion of business value is at risk due to water scarcity, pollution and climate change.

‘[We are] very aware that the use of water is tied closely to people’s livelihoods, and that many existing users are contributing to economic growth and job creation,’ according to South Africa’s Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS). However, in line with its environmental and social mandate, the department has initiated sweeping amendments to the National Water Act of 1998 and the Water Services Act of 1997 that hold serious implications for businesses that rely heavily on water resources or have potential environmental impacts related to water usage, particularly in mining, forestry and agriculture.

Both pieces of legislation – the National Water Amendment (NWA) Bill and the Water Services Amendment (WSA) Bill – were simultaneously released in November 2023 as part of a suite of documents for public comment. In mid-2024, they were still due to be introduced to Parliament. The newly appointed Water and Sanitation Minister, Pemmy Majodina, has confirmed that she will continue with her predecessor’s reforms and improvements of the country’s dysfunctional water sector

‘The DWS is currently reviewing the public comments received,’ wrote Paula-Ann Novotny and Garyn Rapson, partners at Webber Wentzel law firm, in mid-July. ‘The challenges facing the water sector have largely focused on equitable allocation of water resources, sustainability issues, financial challenges, infrastructure degradation and maintenance issues, and service delivery as well as accountability failures,’ they write. ‘A lack of enforcement against non-compliant water-services authorities (municipalities) has been a key gap, as well as the lack of protection of vulnerable or strategic water resource areas and recognising climate change impacts. The proposed amendments to the NWA and WSA seek to address some of these challenges.’

Typically, this requires trade-offs between environmental protection and economic activities. The NWA Bill proposes, for example, to include a new section (Chapter 3A) governing the protection of water source areas.

‘These proposed protections have been welcomed by many, but they also propose to impose express restrictions on sectoral development activities within water source areas, including prohibitions against issuing water-use licences, on underground and opencast mining; forestry plantations; and agricultural activities,’ says Webber Wentzel’s environmental team. ‘The proposed prohibitions on transfers of water use authorisation and trading in water, as well as the proposed overhaul of the Existing Lawful Water Use [ELU] regime, are also primarily directed against the agricultural industry.’

Water trading allows water-rights holders to sell their excess water to others who need more water. Webber Wentzel points out that the proposed prohibition on water trading is a result of a Constitutional Court case (Minister of Water and Sanitation and Others v Lötter N O and Others), which found that the current sections allow for the trading of water.

Why does this matter? By seeking to shut these transfers and trading down and prohibiting ‘surrender’ of a water allocation in favour of a third party, the NWA Bill could curtail agriculture investment and exports, and make South Africa less attractive to foreign investors, says Wandisile Mandlana, a Bowmans’ partner specialising in environmental and regulatory law.

‘The private trading in water allocations between neighbouring farms, surrender of an allocation in favour of a neighbouring property, and distribution of water allocations between properties to increase crop yields are frequently mechanisms for unlocking additional planting, crops and investment in agricultural areas,’ he explains.

For privately owned family farms, it’s not only the ban on water trading, transfer and surrender of their allocations that are contentious, but also the fact that the equitable access provisions of the amendments could curtain their applications for water allocations. The bill proposes to place greater emphasis on past racial and gender discrimination as a deciding factor in Water Use Licence Application consideration. The DWS has noted that only 2% of the water is allocated to historically disadvantaged individuals, as a large portion of water is allocated by means of the ELU regime in the hands of previously advantaged individuals, according to Webber Wentzel. The department proposes to discontinue the ELUs, as it finds that these historic water use entitlements mainly benefit white commercial farmers.

Once the amendments come into effect, only the DWS may make any ‘new’ allocation, says Mandlana. He cautions that the department can apply its own decision-making criteria, including equitable access, in deciding whether or not to grant to transfer. ‘The amendments also allow for “reallocation of water”. The bill is not clear regarding whether this could allow the minister to interfere with an existing water use licence allocation.’

Another issue under debate is the proposed strict liability of company directors and municipal managers for non-compliance with the water legislation. This could have serious consequences on some industries, particularly mining.

Carlyn Frittelli Davies, a consultant in ENSafrica’s natural resources and environ-ment practice, explains that Section 156A of the NWA Bill would mean ‘that the fault on the director’s part is irrelevant and they will be held personally liable’. Instead of this provision, a better recommendation would be to take a ‘vicarious liability’ approach in line with the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), says Frittelli. ‘This would mean that a director would only be held liable if they failed to take all reasonable steps to prevent the commission of the offence from occurring.’

Both amendment bills prioritise stricter environmental regulations and penalties for non-compliance. However, the ENSafrica team says some experts are sceptical about this approach, because it fails to address a fundamental issue – many households do not have access and security of water.

‘While the bill may improve the safeguarding of water sources and redressing water inequality, the basic human right of having drinking water of a certain quality is on the decline,’ says Frittelli. ‘As it currently stands, the DWS is incapable of directly intervening where a municipality has failed to provide clean drinking water and must instead request that the relevant province intervenes.’ However, the new bill gives the DWS the power to issue directives, and it provides recourse where a municipality has failed to comply with a directive to meet minimum standards within the prescribed time frame, she says.

‘Unfortunately, these directives are not seen as a promising manner in which to hold errant municipalities accountable based on the fact the similar directive under NEMA have over the years been ignored or taken extremely long before being effective.’

Earlier this year, then-Minister of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu called for a National Register of Polluters, saying ‘we want those in positions of authority, mayors, CEOs of companies to have their names in the register so that they account for the neglect that leaves our rivers polluted’. Such a ‘name and shame’ register would assist with public pressure to hold transgressors accountable, but only when coupled with administrative, civil and criminal action.

While enforcement actions are important, Mandlana highlights that some of the municipalities’ breaches are a result of backlogs in licensing and infrastructure decay. Therefore, he says, South Africa needs a holistic solution to solve its water crisis – one that includes co-ordinated enforcement actions, investing in public infrastructure and resolving challenges relating to capacity and resources.