Globally, almost 40% of all installed software is unlicensed; in other words it is pirated – or, to be blunt, stolen. According to the Business Software Alliance (BSA), a global trade group of software producers, in its oft-quoted 2018 report on software management, it costs the global software industry an estimated US$359 billion a year to fix malware infections from counterfeit and unlicensed software, and up to US$10 000 to fix a single computer – most likely more than it would have cost to buy the licensed software in the first place.

Not only is it illegal to instal pirated software, it can also be dangerous. The Hustle online magazine shares the cautionary tale of a final-year undergrad student at Lagos University who had saved for months to buy a second-hand laptop but couldn’t afford the extra NGN50 000 to wipe the system clean and instal licensed software. Instead a PC technician sold him pirated versions of Windows 7 and the Microsoft suite for NGN2 000. Needless to say, when he was due to hand in his dissertation, malware scrambled his laptop, making his thesis inaccessible. He wasn’t hacked; his pirated software made him susceptible to a malware attack.

Microsoft recently estimated that only a third of PCs shipped into Africa included genuine software. ‘Because of this, data breaches and malware attacks have risen significantly, resulting in loss of important data and decreased productivity.’ In an attempt to forestall the sale of pirated versions of its software in emerging markets, Microsoft launched its Windows PC Affordability in Africa Initiative in 2019, working with its major PC partners, including Acer, Asus, Dell, HP, Intel and Lenovo, to improve the uptake and affordability of genuine software across the continent.

The overall rate of pirated software across the Middle East and Africa is 56% with a commercial value of more than US$3 billion, according to the BSA.

Libya and Zimbabwe recorded the highest numbers of users of unlicensed software at 90% and 89% respectively. South Africa, according to the BSA, had a recorded rate of unlicensed software of 32%, the only country on the continent to score below 50%.

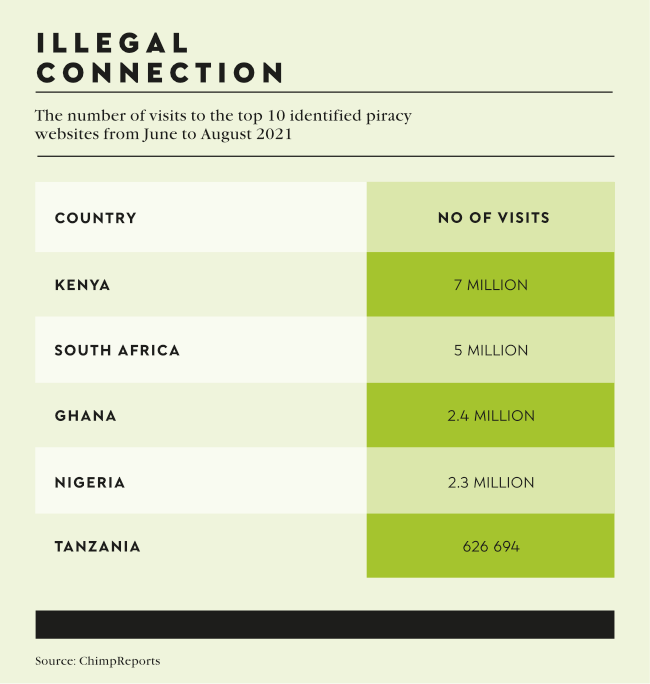

More recently, data collected by software security company Irdeto shows that from June to August 2021, users in South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya and Tanzania made a total of 17.4 million visits to the top 10 identified piracy sites on the internet; about 5% of the global total of 345.4 million visits. The content most pirated ranged from software to literature and video content.

‘Any time someone accesses, shares or sells copyrighted content without authorisation, they are committing content piracy,’ Mark Mulready, VP of cyber services at Irdeto, tells ChimpReports.

Saba and Company Intellectual Property, active in the Middle East and Africa, writes in a recent online post that software piracy, ‘not only poses significant financial losses for developers and businesses but also undermines innovation and creativity in the software industry’.

There’s also significant risk to the user of pirated software, including legal repercussions and, like our student in Lagos, security threats. ‘Pirated software often contains malicious code, including malware and viruses, posing a serious cybersecurity risk. Your company’s sensitive data may be compromised, leading to data breaches and potential financial losses,’ the company says. An additional consequence of using pirated software is not having access to updates or software support.

In South Africa, software – like art, music and literature – is protected under the Copyright Act 98 of 1978, which covers the unauthorised access, distribution or reproduction of copyrighted content.

In short, the work belongs to its creator and you must pay for the right to use it. But with software, it’s not that straightforward.

Andrew Marshall, director of legal firm Dingley Marshall, writes that according to the Act, the author of software is defined as ‘the person who exercised control over the making of the computer programme’, pointing out that South Africa’s courts ‘have not set out a hard-and-fast rule for what “control” means in the context of making a computer programme, but certainly the commissioner of a computer programme does not have to be in direct supervision of the programmer to be considered to control the making of the computer programme. It is enough if the commissioner – the person who orders the programme to be written – sets out detailed instructions to the programmer and the programmer submits the work to the commissioner for approval as it is completed’.

Fatima Ameer-Mia, a director at legal firm Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, says that when ‘the work is created in the course and scope of employment – whether under a contract of service or apprenticeship – the employer will hold the copyright. Where a computer programme has been commissioned, the person commissioning the work would be the author; that is, where a company has commissioned a developer to create an AI algorithm, the author and therefore owner of the copyright would be the company that commissioned the work, and not the developer, unless stated otherwise in an agreement’.

Marshall says that to avoid the pain of trying to find out the specific author of programming code, it is advisable to work out an agreement upfront.

‘Depending on the type and form of technology, there are various other ways to protect one’s intellectual property interests in South Africa, including, but not limited to non-disclosure agreements; copyright; trademarks; and patent protection,’ says Ameer-Mia.

Parliament is currently considering amendments to the Copyright Act intended to give creators a greater slice of the pie. However, there are concerns that the Copyright Amendment Bill of 2017, which is still languishing before Parliament, will do more harm to creators, including software developers.

Writing in Techcabal, Webber Wentzel partner Carla Collett argues that copyright serves two broad functions in society. ‘It reassures business and investors that the works they commission, license and invest in are protected and can be commercialised. It also ensures that the artists, authors, programmers, composers and musicians who create the works are fairly and properly compensated,’ she says.

As governments race to adapt copyright legislation fit for an increasingly digital world, the South African government wants to create copyright laws that balance the interests of businesses and creators alike. ‘It makes good business sense, and good economic sense,’ says Collett.

‘Unfortunately, although they attempt to grant creators more rights – including statutorily mandated royalties – the bills [the Copyright Amendment Bill and the related Performers’ Protection Amendment Bill] will inadvertently limit their rights, including by restricting them from freely contracting with businesses on terms that are commercially favourable and aligned with international norms.’

She warns that if the bills are passed, though it’s not likely this will happen in 2023, the legal risk of working with South African creators will increase.

‘What the bills have not considered is that companies will merely move their business and investment to countries that provide the best competitive advantage for copyright protection,’ says Collett. ‘Accordingly, creators from all industries in South Africa will struggle to find partners willing to commercialise their work. This could have two possible impacts.

‘It will either leave creators without a source of income, or it will leave South Africa without creators. Either way, South Africa will lose investment and economic growth as well as the opportunity to cultivate more abundant creative and digital industries.’