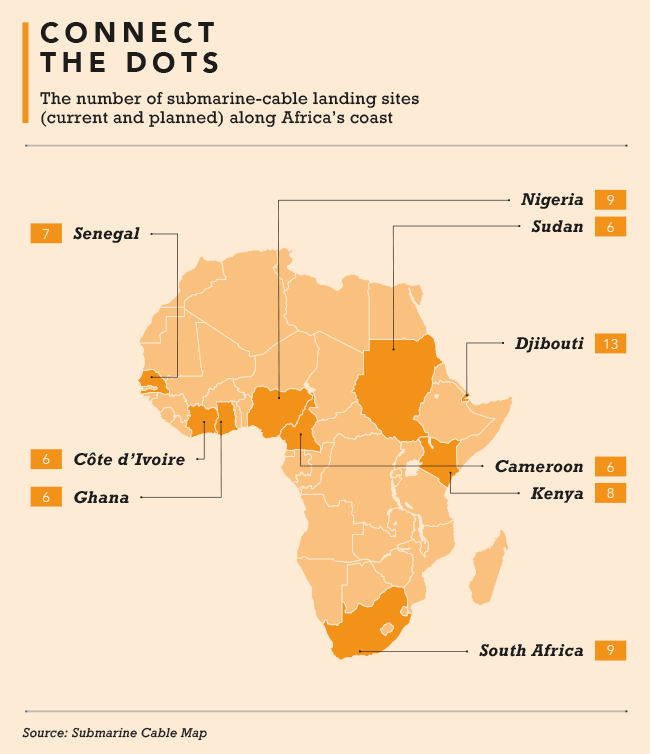

It’s so nice to be beside the seaside… Especially in Africa, where – at locations such as Mombasa, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Accra, Maputo and Cape Town – ultra-fast broadband internet lands on the beaches via high-throughput undersea cables. Lagos, Libreville, Pointe Noir, Durban… Those landing points mean that Africans along the coast have access to submarine broadband, piped in directly from Europe. Move into the continent’s massive interior, though, and the fast connections dry up.

The World Bank estimates that around 45% of Africa’s 1.3 billion people are further than 10 km from fibre-network infrastructure. That’s higher than any other continent, and for sub-Saharan Africa it provides a clear snapshot of the current state of the region’s fibre internet. In 2000, the whole of Africa had less international internet bandwidth than the tiny European duchy of Luxembourg (a country about a quarter of the size of Kinshasa). ‘Two decades later, despite some progress, much of Africa is still unconnected and large populations cannot fully realise the benefits of connectivity,’ according to the World Bank.

‘Most internet adoption in Africa is driven by mobile connections, and the range of 3G/4G technology is location-dependent,’ it adds. ‘But if those cell towers are not served by fibre (and rely instead on microwave or satellite), then the signal speed and capacity is typically lower, likely restricted to 2.5G and not true broadband.’

UNESCO’s Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, meanwhile, found in its Connecting Africa through Broadband report that ‘nearly 1.1 billion new unique users must be connected to achieve universal, affordable, and good-quality broadband internet access by 2030, and an estimated additional US$100 billion would be needed to reach this goal over the next decade’. This ‘significant infrastructure undertaking’ it notes, will require the deployment of nearly 250 000 new 4G base stations and at least 250 000 km of fibre across the region. ‘It also requires rolling out satellites, WiFi-based solutions, and other innovations to reach an estimated population of nearly 100 million that lives in remote rural areas that are currently out of reach of traditional cellular mobile networks.’

Reading those numbers, it’s easy to under-estimate the extent of the undertaking required – 250 000 km, after all, is the distance between Cape Town and Johannesburg … 178 times. Fibre providers across Africa are working to close that gap. Facebook, for example, recently announced the expansion of its 2Africa undersea cable, adding Seychelles, Comoros and Angola (as well as a new connection to Nigeria). Originally designed to serve 1.2 billion people in Africa, Europe and Asia, it will now reach 3 billion.

In South Africa, Investec recently announced a ZAR2.5 billion debt package for fibre-infrastructure provider MetroFibre, which will see the firm expand its fibre network roll-out across the country – primarily into underserviced businesses and homes. ‘There’s a massive demand for fibre connectivity in many outlying regions,’ says MetroFibre financial director Wayne Edwards. ‘Filling that gap makes sense not only from a business perspective but also from a socio-economic upliftment standpoint.’

Dark Fibre Africa (DFA) is also looking to bring connectivity to outlying areas, recently launching a year-long feasibility study in collaboration with the US’ Trade and Development Agency to look into the possibilities in rural South Africa. ‘The study will contribute significantly to shaping our approach in extending the reach and access to digital infrastructure to the less connected,’ Vino Govender, DFA’s chief strategy, mergers and acquisitions, and innovation officer, said at the launch. Since it started rolling out its fibre network in 2007, DFA has deployed more than 14 000 km of ducting infrastructure in South Africa’s major metros, secondary cities and smaller towns. In recent years the company has been cementing its role as a wholesale, open-access fibre-infrastructure and -connectivity provider, leasing its secure transmission and backbone fibre infrastructure to telecoms operators, ISPs, businesses, municipalities and so on.

Yet, as Govender points out, widespread digital connectivity cannot be driven from only the supply side. ‘Demand and volume of consumption of services play a significant role in determining the return profile of investments made by network operators in the infrastructure, platforms, product development and services that are required to deliver quality connectivity and digital services,’ he writes in an online piece. ‘While a lot of efforts have been made on the supply side – including policy, the licensing of new entrants and the release of spectrum – it requires equal or even more efforts on the demand side to enable the adoption and use of services that in turn feeds a cycle of reinvestment.’

MTN, Vodacom, Vumatel, Vox, Dark Fibre Africa. The country’s major players have all continued – and accelerated – their fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) and fibre-to-the-business (FTTB) roll-outs.

The 2020 State of the ICT Sector report by the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) notes that FTTH and FTTB subscriptions both surged 168.2% nationwide between 2015 and 2019, prompting Jessica Spira, business development director at Rand Merchant Bank, to remark that ‘in these times of great economic uncertainty, the fibre industry is a great South African success story and proof of how the private sector can drive economic development’.

Meanwhile in the DRC, Liquid Intelligent Technologies (LIT) recently opened a 2 500 km fibre network that stretches from Muanda at the coast, to cities such as Kikwit, Kananga, Mwene-Ditu, Kolwezi and Lubumbashi, deep in the interior. A second line will go even further, 4 000 km into the eastern DRC.

Those two lines will make DRC the 14th member state of the One Africa Network, which has more than 73 000 km of fibre-optic cables linking Cape Town to both Lubumbashi and Dar es Salaam. And while communications infrastructure is officially (and legally) the responsibility of the state-owned Société Congolaise des Postes et Télécommunications, the Congolese government granted a waiver to LIT allowing it to build the backbone infrastructure. ‘The DRC has only 4 000 km of network, whereas the need is for 50 000 km,’ according to Augustin Kibassa, Congolese Minister of Posts, Telecommunications and New Information and Communication Technologies. ‘We have made the choice to move the country forward.’

LIT, meanwhile, opened its fifth hyperscale data centre in South Africa and announced its intention to build 10 more in other countries on the continent. ‘We have now secured over US$500 million in equity and loans to build what we call “Project Decima” – the largest data centre campuses in 10 African countries, each representing an investment of US$50 million,’ says Liquid founder Strive Masiyiwa. ‘Each of these facilities is interconnected with our 100 000 km fibre network that spans the entire continent.’

Add to that Orange’s commercial launch of Djoliba – a terrestrial fibre-optic backbone covering Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria and Senegal, natively interconnected with those countries’ domestic networks – and you have picture of a rapidly maturing, continental fibre industry.

In an interview with ITWeb, Digital Council Africa CEO Juanita Clark describes a fibre market that is now coming of age. Citing the ICASA report, Clark notes the number of FTTH or FTTB internet subscriptions in South Africa rose from 31 843 to more than 1.6 million between 2015 and 2019. During that time, a slew of fibre industry players have come, deployed fibre, connected homes, and gone – many of them being bought up by larger players through a spate of M&A activity. Those business economics played out in October 2020, when Actis bought a controlling interest in FTTH operator Octotel for ZAR2.3 billion; and again in April, when MetroFibre acquired Link Africa’s fibre networks in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal; and then in September 2021, when open-access fibre provider Frogfoot Networks bought the FTTH assets of Link Africa Western Cape.

As those M&As play out and the industry matures into the usual order of minor players and major players, fibre providers across the continent are already looking to the next frontier. Most of Africa’s metros have fibre cables in place already. Now it’s time to start looking into the harder-to-reach places.

That’s no easy undertaking. ‘For all stakeholders, rural areas – with their sparse landscapes – add another layer of complexity,’ says Keoikantse Marungwana, senior research and consulting manager at market intelligence firm IDC. ‘ROI and payback periods in rural markets are much more difficult compared to high-density urban and peri-urban areas,’ he says. ‘That said, there is still an opportunity for businesses to fully realise the potential of FTTX despite the challenges. Organisations that adopt this technology can fully realise their digitalisation needs through a stable, high-speed and low-latency connection. They can develop their cloud strategies and accelerate cloud adoption, and leverage the potential of the hybrid or work-from-home models.’

In Africa, an entire continent of people is waiting for exactly that.