As statements go, this one was pretty bold. In a full-page, paid-for, open letter published in the Sunday Times in early June, Telkom CEO Sipho Maseko called on the political leaders of South Africa to have a ‘national conversation’ about the importance of ICT infrastructure in growing the country’s economy – which, he emphasised, had ‘shrunk by more than 2% in the first quarter of 2018, the worst decline in almost a decade’. That downward trend, Maseko told South Africa’s political alphabet soup – the ANC, DA, UDM, EFF, IFP and COPE – ‘should jolt us into action’.

It was not a long letter – barely 260 words in total – but twice Maseko pointed to spectrum as a potential solution. ‘One way of doing this is to release spectrum to unlock value and set the country on a trajectory to participate in the Fourth Industrial Revolution,’ he wrote, adding that spectrum, ‘which is a high-impact, finite and scarce national resource, is at the heart of unlocking value across all sectors in the digital economy. ‘We need to use it and other resources at our disposal, to ensure that we enable long-term economic growth’.

The frustration in Maseko’s letter was tangible. While the rest of the telecoms world buzzes about the possibilities of next-gene-ration 5G technology, South Africa has not yet allocated spectrum suitable for building 4G networks. Instead, operators have been forced to reallocate their 2G and 3G spectrum to offer 4G. And as demand for connections increases (especially in urban areas), those operators are running out of options.

Compounding the issue, South Africa has still not completed the switch from analogue to digital terrestrial TV, even though the original deadline – set by the International Telecommunication Union – passed in June 2015. This means that in the past three years, the spectrum in the prized 700 MHz and 800 MHz band has been used to deliver analogue TV signals instead of being reallocated for mobile broadband.

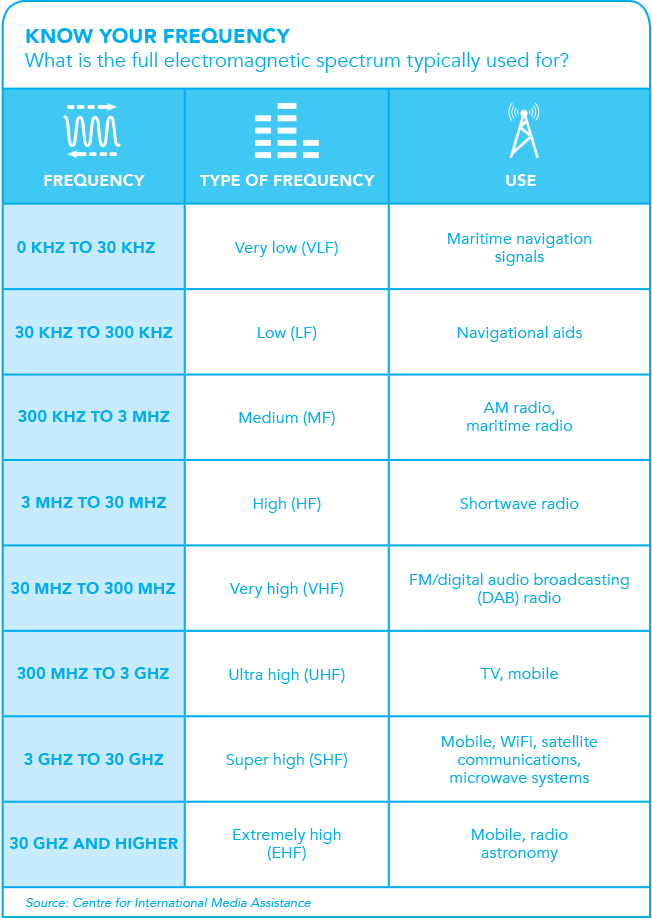

This is where the debate (which, for reasons that will soon become clear is a fierce and complicated one) turns technical. The ‘spectrum’ that Maseko was referring to is the electromagnetic one, which carries the signal required for – among others – TV broadcasts and mobile phone communication.

The 700 MHz band penetrates walls fairly easily, making it perfectly suited for cellular and/or long-range wireless broadband. The 800 MHz band, on the other hand, is well suited for delivering strong indoor LTE coverage, and for providing LTE in rural areas. Digital TV uses less spectrum than analogue, so when broadcasters make the switch, it frees up part of that spectrum. Mobile operators are desperate to use that band, as it allows them to deploy the capacity and coverage of data networks at a lower cost. No wonder, then, that in 2014 the Department of Communications valued that 700 MHz band (known as the ‘digital dividend’) at about ZAR3.5 billion over the period 2015 to 2026.

As long as the lower band spectrums are taken up, and while the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) does not license access to those bands, South African mobile operators will have to continue deploying data networks on a higher band spectrum (1.8 GHz or 2.1 GHz) to build 4G and LTE networks. These are, however, pricier and require more towers, antennae, power and infrastructure.

ICASA had planned to auction spectrum in the 700 MHz, 800 MHz and 2.6 GHz bands, but in September 2016, Telecommunications and Postal Services Minister Siyabonga Cwele succeeded in halting that auction. In early 2017, ICASA postponed the auction indefinitely. Meanwhile, the demand for spectrum has only increased, creating a ‘spectrum crunch’ and – so the argument goes – leaving South African consumers paying more than they should for mobile data.

In early 2018, Ahmore Burger-Smidt, director at Werksmans Advisory Services, spoke to MyBroadband about a number of key pieces of new legislation relating to the ICT sector. While looking at the Electronic Communications Amendment Bill, Burger-Smidt noted that it does not address that spectrum crunch, which she highlighted as being ‘the single-biggest issue’ facing the local telecoms industry.

‘The withholding of spectrum will result in mobile operators needing to scale back plans for continued growth into rural areas,’ she wrote. ‘Operators will have no option but to refarm the spectrum and to further densify the network at increased cost, to cope with the ever-growing urban demand for data. As a consequence of this, data costs will not be driven down, with the impact being worst felt by South Africa’s most economically marginalised communities.’

The amendment bill does, however, provide a possible solution to the problem of how that high-demand spectrum should be allocated. The idea, introduced in the National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper, is that the remaining spectrum will be assigned to a wireless open-access net-work (WOAN) provider.

South Africa’s big telecoms operators have criticised the bill, saying it will undermine investment and damage the industry. The same operators are similarly critical of plans to reserve most (possibly all) radio frequency spectrum that can be used for wireless broad-band for the WOAN, and of threats that their existing spectrum licences – which they have used to deploy their 2G, 3G and 4G mobile networks – would be taken away. Ultimately, the operators promised to buy capacity on the WOAN, while the government pledged not to revoke the existing spectrum licences until they come up for renewal in 2028.

The debate – fierce and complicated as it is – continues. In March, at a media briefing to announce the MTN Group’s full-year results for 2017, MTN SA CEO Godfrey Motsa was clear on what he thought about the WOAN. ‘The creation of a monopoly in the WOAN is basically a terrible idea and flies in the face of what the national development plan says and what the government is actually trying to achieve,’ Motsa told reporters. ‘Our position is that we should stick to the hybrid model.’ This would be to create a WOAN, then the spectrum that remains afterwards would be ‘put it into auction’.

He added: ‘We believe there are no physics that says that one operator needs so much spectrum; there would be a lot of inefficiency in that. So we are saying adopt the hybrid model.’ An industry consultation workshop on the Electronic Communications Amendment Bill was held for 43 industry stakeholders, and while Vodacom shared MTN’s support for the hybrid model, other players thought differently. ‘You have Telkom saying spectrum should only be allocated to the WOAN, and then also a lot of private lobbyists who are [in agreement],’ according to Motsa, in remarks later reported by ITWeb. ‘Then, in our position, there is us, the red guys.’ (Yes, that’s what MTN call their rivals Vodacom.) ‘Face-book and lobbyists on that side too. I would say the majority of people actually support our position.’

Motsa insisted that ‘there is more agreement than disagreement between opera-tors’. He said that the idea of the WOAN is universally supported, and the urgency of allocating the spectrum is recognised. ‘The only area of difference is the monopolisation, or that it’s shared among the players.’

At the end of May, Cwele told the 5G Huddle 2018 conference in Durban that a decision on the future of spectrum allocation in South Africa would soon be made by Cabinet. ‘Last year, we consulted widely on the implementation of spectrum policy and we have found a consensus where we have said in view of the large investment made by the industry over the years, we must assess what would be the requirement of the wireless open access network in terms of spectrum,’ he said.

Cwele added that the outcome of a government-commissioned Council for Scientific and Industrial Research study into the spectrum needs of a sustainable WOAN, was in the Cabinet process for consideration and approval. Cwele cited President Cyril Ramaphosa’s comments during May’s budget vote speech. ‘He is very serious about attracting investment,’ said Cwele. ‘If there is additional spectrum that can be licensed, we should do that without any delays.’

Or, as Telkom’s CEO might put it, the decision-makers should be jolted into action. As long as the debate rages on, South Africa’s ICT sector growth will be limited, its mobile data costs will be unnecessarily high, and its spectrum crunch will only get tighter.