The dream of a single power grid stretching from Cape Town to Cairo is coming together faster than many might have expected. Africa’s power deficit is well known and characteristic of the continent’s underdevelopment: it generates and uses less electricity per capita than any other.

In its 2015 report Brighter Africa, international consultant McKinsey points out that while the region has 13% of the world’s population, it contains 48% of all the people globally who do not have access to electricity. The total volume of electricity consumption in sub-Saharan Africa is even lower than that of Brazil.

McKinsey is, however, optimistic about Africa’s future prospects. The company’s 2010 Lions on the Move report was hugely influential in alerting global investors to the potential of the continent. McKinsey believes the emerging industrial economies of Africa have a pent-up demand for electricity consumption well beyond that presently supplied. ‘Africa is starved for electricity,’ it argues.

Focus has tended to be on new productive capacity across the continent. However, the creation of electricity grids requires an entire package of projects, with transmission and distribution of equal importance. The late Lawrence Musaba, then co-ordination centre manager of the Southern African Power Pool, pointed out in 2014 that new generation capacity would require new transmission networks ‘to evacuate power from generation stations to load centres’. If the continent is to realise its potential, it’s important that this capacity extend across national boundaries. The areas with demand for electrical power are not necessarily the same places that power is best generated.

McKinsey estimates that for every US$10 spent on generation capacity, sub-Saharan Africa needs to spend US$7 on transmission and distribution infrastructure (a total of US$490 billion on generation capacity and US$354 billion on transmission and distribution). The consultancy bases its electricity demand projections on anticipated economic growth and expects a total electricity consumption of some 1 600 terawatt hours (TWh) by 2040, led by industrial and residential demand. This represents a massive increase from the 423 TWh consumed in 2010.

The cross-country dynamic injects considerable complexity into the issue. In all African countries, transmission of electrical power is primarily a responsibility of national state-owned companies. Co-operation between the professional staffs of these companies is generally good but they do ultimately take their direction from politicians and this is where complications can arise.

There are several institutional models used in different countries. In Kenya, for example, one company – Kenya Power – is responsible for electricity transmission, as well as the supply to customers and billing. Another company, KenGen, produces most of the country’s power. In between the generation and distribution, another state-licenced company, Kenya Electricity Transmission Company (Ketraco), is entrusted with the transmission infrastructure.

In Ethiopia, all parts of the process are managed by a single parastatal, the Ethiopian Electrical Power Corporation. In South Africa, the division of responsibilities follows yet another path, with state-owned company Eskom handling generation and transmission, while most (but not all) distribution is in the hands of the municipal sphere of government.

There are a number of good reasons for keeping transmission firmly in the grasp of national companies.

Energy security is one of these. The transmission system is critical to dealing with the problem of cascading failures. These are occasions when one part of the system fails (often as a result of excessive demand), which forces nearby nodes to take up the slack. But these elements also become overloaded and fail in turn, leading to a vicious circle that can lead to entire regions blacking out.

A cascading failure led to a blackout in India in July 2012, affecting an estimated 620 million people, reportedly the biggest episode in history.

Cascading failures can be headed off by judicious disconnection, but doing this effectively requires central control. Another reason for keeping transmission in the jurisdiction of national companies is that adequate privatisation models do not exist, at least not for developing countries. On the electricity-generation side, the resources of the private sector can easily be mobilised through independent power producer (IPP) contracts.

Many contracts can be issued. In South Africa, for instance, the IPP programme spans 92 individual projects now and the system will never depend on the performance of just one of these producers. In transmission, however, the only way to introduce the private sector is by contracting out the management of entire regions, with all the risks of systemic failure.

It is not far-fetched to suggest that electricity supply is the single most important benchmark of Africa’s development

State entities are seldom efficient, however, and it was for this reason that in March the World Bank issued a request for ‘expression of interest’ in an effort to understand how independent power transmission projects could be designed to work in Africa.

Power transmission becomes less efficient as distance increases because friction reduces the electrical charge. In real economic terms, it is cheapest to supply power to customers located closer to generation plants. But one of the roles of national transmission companies is to (artificially) even out the cost, effectively through cross-subsidisation, so that businesses face the same electricity charges across an entire national market.

The accepted way to deal with fluctuations in both demand and generation capacity across African countries is through regional power pools, from which countries are able to buy and sell electricity to each other. These require agreements between national governments to regulate the integration of power systems across national borders, which can be a difficult process. In 2016, Egypt appears to have withdrawn from the East African regional power pool over its long-term concerns about the impact of Ethiopia’s hydroelectric schemes on its own water security.

Ethiopia has been building the Grand Renaissance dam on the Blue Nile, which will significantly cut the flow for Egypt’s rapidly increasing population. The contractor, Salini Impregilo S.p.A., is a Milan-based engineering firm responsible for both Lake Kariba in the late 1950s and, currently, the widening of the Panama Canal.

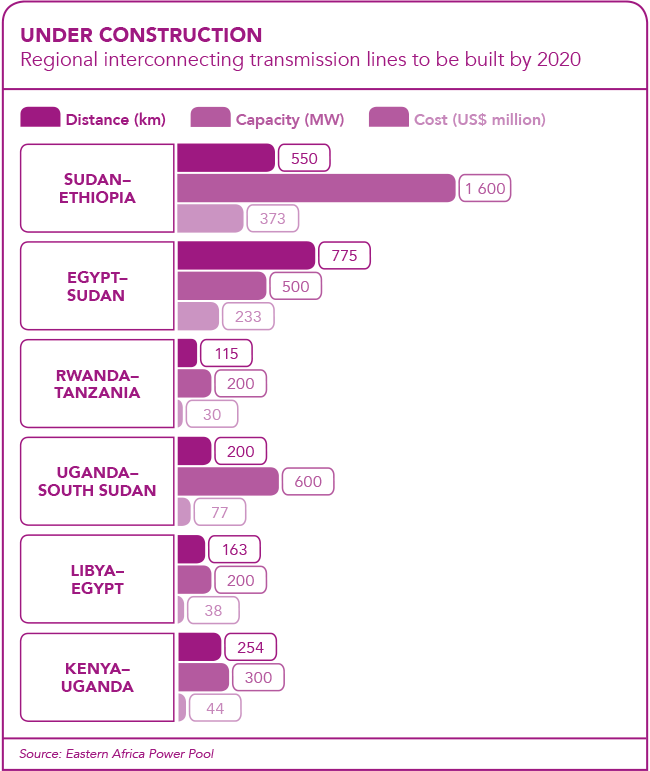

In early 2016, the installation of the first two 375 MW turbines was under way at the dam and the government of Ethiopia expected production to start ‘within months’. In May, Salini Impregilo signed a new contract to build another hydroelectric scheme in Ethiopia, the 2 200 MW Koysha dam on the Omo river. Egypt has refused to sign the master plan for electricity interconnections between 10 African countries – Burundi, DRC, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Libya and Uganda – scheduled to start construction later this year.

The interconnection between Kenya and Ethiopia is, however, already going ahead. A contract was signed between the Kenyan parastatal Ketraco and a consortium, consisting of Siemens and Spanish company Isolux Corsan, for the construction of the critical substation at Suswa, about 80 km north-west of Nairobi. The project will facilitate the connection of 2 000 MW of capacity in either direction, at a cost of US$230 million. The line will stretch for 1 045 km and its main Kenyan node, Suswa, is intended to be the hub of the entire East African grid.

Announcing the contract late last year, Ketraco MD and CEO Fernandes Barasa said the objective was to ‘ensure affordable access to electricity [for Kenya] … due to the cheap hydropower from Ethiopia’. It will also enable Ethiopia to buy Kenyan electrical power in the dry season, should hydrogeneration be affected. Construction is expected to be completed by the end of 2017.

There are other interconnection projects going ahead in many parts of the continent. Tanzania is interconnected with the Kenyan grid through the Iringa-Shinyanga project, culminating in 2018, and with Zambia through the Iringa-Mbeya project, scheduled for completion in 2019.

A second 142 km interconnector line has been completed between the DRC and Zambian copper fields, increasing available capacity to 500 MW. (It supplements the old existing line, built in 1956.)

One of the biggest planned projects is ZiZaBoNa, which hinges on a substation to be constructed at Livingstone in Zambia. Named for the four countries it intends connecting – Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and Namibia – together with South Africa’s Eskom, the project will add a 400 kV western corridor to the Southern African power pool.

This will ease congestion on the established North-South corridor and enable the countries involved to trade electricity with each other as well as South Africa. As matters stand, when Namibia wants extra power that is available in Zimbabwe, it has to be ‘wheeled’ through South Africa.

ZiZaBoNa illustrates the interconnectedness of electricity infrastructure in another way. A number of generation projects are waiting for confirmation of the interconnection before going ahead. Zimbabwe and Zambia are contemplating a joint 2 400 MW project at Batoka gorge. Botswana’s Morupule coal-fired power station will be integral to the project but also requires expanded transmission infrastructure, linking to Maun in the north of the country.

It is not far-fetched to suggest that electricity supply is the single most important benchmark of Africa’s development. A critical part of it – currently proceeding at high speed – is the development of more sophisticated systems needed to trade electricity between countries.

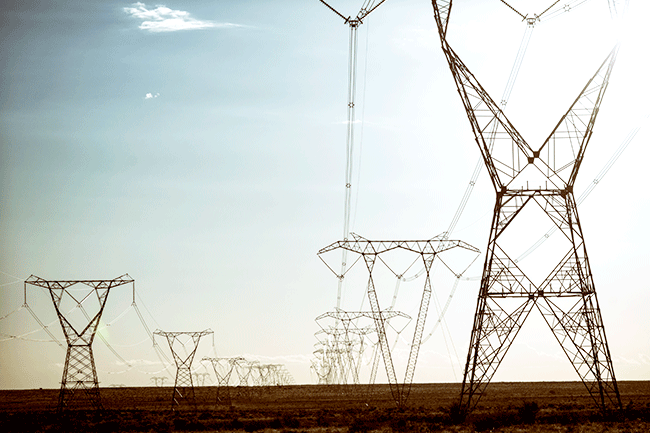

The concrete realisation of this is the highly visible erecting of the power lines and substations that are currently interconnecting the continent.