You don’t have to spend much time on the internet to find reports of high-profile cyberattacks. In April, South Africa’s state-owned Small Business Development Agency (Seda) fell victim to one, as hackers locked them out of their own computer systems and demanded a ransom payment before they would unlock the data again. That came just days after South African fitness group Virgin Active took its computer systems offline after being targeted by ‘sophisticated cybercriminals’; which in turn came as investment group PPS confirmed that it, too, had been hit by a cyberattack. In May, Nigeria’s National Information Technology Development Agency issued a national alert about IGVM, a new wave of ransomware that targets documents, images, videos and other data.

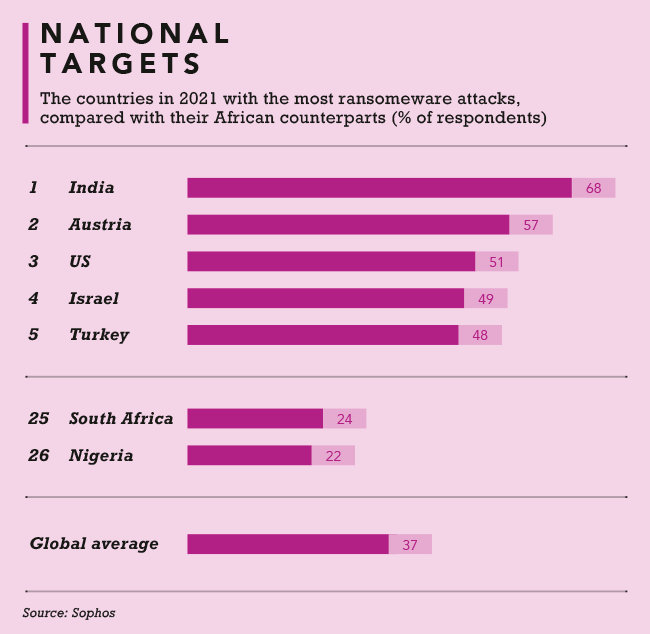

And so the list goes on. Cyberattacks have spiked during the pandemic, and one would assume that ransomware attacks have increased as well – yet, according to the latest State of Ransomware 2021 report by cybersecurity firm Sophos, ransomware attacks actually dropped worldwide from 51% of survey respondents in 2020 to 37% in 2021.

There’s a sobering reality behind those numbers. ‘We’ve seen attackers move from larger-scale, generic, automated attacks to more targeted attacks that include human hands-on-keyboard hacking,’ according to Sophos principal research scientist Chester Wisniewski. ‘While the overall number of attacks is lower as a result, our experience shows that the potential for damage from these more advanced and complex targeted attacks is much higher. Such attacks are also harder to recover from, and we see this reflected in the survey in the doubling of overall remediation costs.’

There’s a sobering reality behind those numbers. ‘We’ve seen attackers move from larger-scale, generic, automated attacks to more targeted attacks that include human hands-on-keyboard hacking,’ according to Sophos principal research scientist Chester Wisniewski. ‘While the overall number of attacks is lower as a result, our experience shows that the potential for damage from these more advanced and complex targeted attacks is much higher. Such attacks are also harder to recover from, and we see this reflected in the survey in the doubling of overall remediation costs.’

Ransomware hackers aren’t interested in locking you out of your laptop. Most users have their data backed up in the cloud, and it’s cheaper to throw a computer away than to engage with hackers who might not even release your data after you’ve paid them. Instead, those hackers are aiming for the bigger fish: large corporates with deep pockets, and large-scale utilities with millions of people counting on them to deliver services.

In March 2021 major US insurance company CNA Financial announced it had suffered a ‘sophisticated cybersecurity attack’. The company called in external experts and law enforcement, but – according to a Bloomberg report – started negotiating with the hackers on the side. The report states that CNA paid the hackers US$40 million which, while not as much as the US$60 million the hackers had originally demanded, nevertheless made it one of the biggest ransomware payments ever. It was also, according to virtually every cybersecurity expert, a US$40 million mistake.

Security firm Kaspersky recently reported that 42% of South African victims of ransomware attacks end up paying the criminals to try recover their data. The report found that 36% of respondents paid less than US$100; 31% paid between US$100 and US$249, and 19% paid between US$250 and US$1 999.

Yet here’s the rub: according to the same report, ‘whether they paid or not, only 24% of victims were able to restore all their encrypted or blocked files following an attack. Sixty-one percent lost at least some files; 32% lost a significant amount, and 29% lost a small number of files. Meanwhile, 11% who did experience such an incident lost almost all their data’.

Kaspersky CEO Eugene Kaspersky was so flabbergasted by this finding that he took to the company blog. ‘Sometimes, reading an article about what to do in case of a ransomware attack, I come across words like “think about paying up”. It’s then when I sigh, exhale with puffed-out cheeks… And close the browser tab,’ he writes. ‘Why? Because you should never pay extortionists. And not only because if you did, you’d be supporting criminal activity.’

There’s more to it than that, though – as Kaspersky points out, using the example of the ExPetr/NotPetya malware that did the rounds in 2016.

‘Since a unique user ID was generated completely randomly, it was simply impossible to decrypt the files. Even the attackers themselves couldn’t do it,’ he writes.

‘So all the money in the world wouldn’t have helped at all.’ Indeed, most cybercrime experts don’t classify ExPetr/NotPetya as ransomware; instead, they call it wipeware. Once your system is infected, it’s as good as wiped.

However, as Kaspersky adds, ExPetr/NotPetya is not an isolated case. ‘It’s not uncommon for cybercriminals to make coding errors. And while sometimes such errors allow us to create a decoder, other times, on the contrary, they prevent even the coders themselves from developing one.

‘There was a recent case when a cybersecurity expert publicly asked a cybercriminal group to fix a bug in its ransomware Trojan to stop affected files from being corrupted irrevocably. It’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry. So, to sum up: if you decide to pay up, just remember there’s no guarantee you’ll get your files back – ever.’

That plea – posted to Twitter in February 2021 by self-described ransomware hunter Michael Gillespie (@demonslay335) – is revealing in its overriding tone of frustration. If you’re going to do it, he seems to be telling the hackers, at least do it right. But what if taking the ransom without releasing the data was their idea all along?

That’s the realisation that’s now dawning on major corporates and utilities across the world. In May 2021 North America’s key Colonial Pipeline, which supplies 45% of the East Coast’s diesel, petrol and jet fuel, was taken offline in a brazen ransomware attack by a group identifying itself as DarkSide.

DarkSide, which has since shut down, apologised for the attack, issuing a statement insisting that ‘our goal is to make money and not creating problems for society’. But that only came after Colonial Pipeline CEO Joseph Blount admitted that he had paid a ransom of

78 bitcoin (around US$4.4 million). ‘I know that’s a highly controversial decision,’ he told the Wall Street Journal. ‘I didn’t make it lightly. I will admit that I wasn’t comfortable seeing money go out the door to people like this. But it was the right thing to do for the country.’

Was it, though? According to a Bloomberg report, DarkSide provided a decrypting tool, but it worked so slowly that Colonial still had to rely on restoring its own backup files.

That’s typical: the Sophos survey found that around just 65% of encrypted data is restored after a company pays the ransom. Yet ransomware victims continue to pay up.

A study by blockchain researcher Elliptic found that DarkSide had received more than US$90 million in bitcoin ransom payments, originating from 47 distinct wallets, before it shut up shop. Further analysis revealed that 99 organisations had been infected with DarkSide’s malware, suggesting that 47% of victims had paid a ransom, with an average payment of US$1.9 million.

‘Our goal is to make money.’ They said so themselves.

And that’s a chilling thought for infrastructure providers across the world, which – like Colonial Pipeline – are prime targets for these attacks. Just ask Eletrobras and Copel, two Brazilian state-owned utility companies that suffered separate ransomware attacks in February 2021; or Johannesburg’s City Power, which was hit by a ransomware attack in July 2019; or Ukrenergo, the Ukrainian national energy company, which was hit by a suspected international cyberattack in the winter of 2015. It’s hard to negotiate (or to refuse to pay) when hundreds of thousands of people are sitting without gas or electricity.

As Josephine Wolff, assistant professor of cybersecurity policy at the US’ Tufts University, muses in a recent interview with Scientific American, ‘what happens if somebody is able to prevent the provision of electricity across some part of the country? The Colonial Pipeline shutdown, though it’s not exactly that, fits into that nightmare scenario of “what do we do if we lose control over our power infrastructure?” What happens if a large part of the banking infrastructure is shut down or impossible to access? What happens if the subway system in a major city is compromised, and it’s impossible to schedule trains or operate transportation?’.

Wolff adds that until now, scenarios like that have mostly been hypothetical. But as the ransomware industry evolves, those scenarios are becoming a frightening reality.

By Mark van Dijk

Images: Gallo/Getty Images