Yes, your internet is slow. But there is a good reason for that. Across Africa, internet connections are – or, at least, have been – slower than in Europe or the US, simply because most of the content being requested is hosted on servers on the other side of the world. Every time you open a web page or stream online video content, your computer or mobile device sends a request to that server, and the data is sent back to you from its host server thousands of kilometres away. Now if that data happened to be stored on a server more nearby, it would reach you a lot quicker (and, come to mention it, a lot cheaper). And your internet would be a lot faster.

That’s precisely why, in October 2016, Netflix deployed a server in Nigeria – and why its Naspers-owned video-on-demand rival ShowMax boosted its own capacity by hosting caching servers in Kenya. The net effect, says Mike Raath, ShowMax head of distribution, ‘is that customers can pull video content from much closer to home, which means faster response time and less buffering’.

At the African Peering and Interconnection Forum, held in Abidjan in August 2017, Funke Opeke, CEO of data centre operator MainOne, challenged Africa’s internet operators to route 80% of the continent’s internet traffic through locally built infrastructure by 2020 – thereby decreasing the continent’s dependence on the ‘tortuous route’ of accessing data from Europe, the US or Asia.

‘Africa needs to retain more local traffic within the continent to drive more value from the internet,’ said Opeke. ‘This can be achieved by leveraging robust internet exchange points and access via local interconnection points and local data centres that provide a platform for different networks to directly interconnect with other operators and exchange traffic, guaranteeing lower bandwidth costs, quicker access to more content providers and carriers, and lower latency for local markets.’

Opeke added that Africa’s growing fibre network density and rising number of world-class data centres are ‘making it much easier for content providers and OTT operators to host and serve data locally’.

Her point about data centres was well timed. These facilities – which store large volumes of data while providing uninterrupted power, cooling and connectivity – are in huge demand across the continent. A study published in late-2015 by research firm Xalam Analytics found that the need for colocation (in other words, the outsourcing of data centre capacity) across Africa was, incredibly, increasing two to three times faster than supply.

Telecoms services providers are racing to meet this demand. In November, Internet Solutions announced a ZAR500 million investment to extend its Parklands data centre in Johannesburg, in what the company is calling the first of its kind at this scale in sub-Saharan Africa. The expanded data centre will provide a total capacity of 572 racks and 2.2 MW of IT power. However, its most significant selling point is its location in Rosebank, within 10 km of both Sandton and Johannesburg CBDs.

‘On completion of the Parklands expansion project, Internet Solutions will boast the most ideally located, carrier-neutral data centre in South Africa,’ Internet Solutions executive of data centres Matthew Ashe said in a recent statement.

‘It hosts the Johannesburg Internet Exchange, and is in close proximity to some of the continent’s most important business centres, which makes this data centre the obvious choice for local and multinational enterprises alike. Thanks to its location, the existing Parklands facility already delivers minimal latency, with capacity set to double on expansion.’

It’s not just Johannesburg, though. In Lagos, the Nigerian government has opened a NGN500 million data centre with enough IT power to enable the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE) to compete with what it calls some of the ‘best exchanges’ in the world. At the launch, Oscar Onyema, CEO of the Nigerian Stock Exchange, said that the facility would be used to reduce latency times and improve redundancy overall.

*Great Fit | Digital marketing for your business

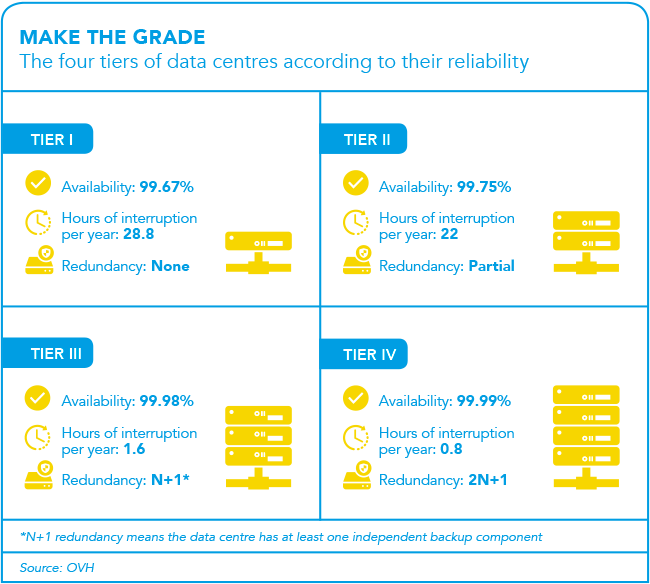

Elsewhere, the East Africa Data Centre in Nairobi recently became the first in Central and East Africa to be granted Tier III Design certification by the Uptime Institute, while ChinaNetCenter announced a partnership with the Djibouti Data Centre network to improve end-user experience across the East Africa region. In Cameroon, French multinational telecoms company Orange opened a new carrier-neutral data centre in Douala this past June, promising to bring greater connectivity to Cameroon and Central Africa.

In March, IBM opened its first data centre in South Africa, promising to deliver low-latency public, private and cloud services to the entire continent. That same month, Teraco revealed its plans to build the continent’s biggest data centre after raising ZAR1.2 billion in debt from Absa to expand its existing site to several times its current size.

‘We will use the funding to further invest in the Teraco Campus in Isando,’ Jan Hnizdo, Teraco’s chief financial officer, said at the time.

‘The site presently has 20 MW of capacity, which needs to all be brought online. We have also purchased land adjacent to the existing site allowing for further expansion. In addition, a component of the funding has also been earmarked for the construction of Teraco’s new data centre in Bredell.’

The Bredell site has 24 MW of power and more than 6 000 m2 of technical deployment space, making it the largest commercial data centre in Africa.

More news came out of the Teraco offices eight months later, when the company was announced as a Microsoft Azure ExpressRoute connectivity partner. This came as Microsoft unveiled its plans to start delivering cloud services, including Microsoft Azure, Office 365 and Dynamics 365, directly from data centres located in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

The company confirmed in a statement that the new cloud regions would ‘offer enterprise-grade reliability and performance, combined with data residency to help enable the tremendous opportunity for economic growth, and increase access to cloud and internet services for organisations and people across the African continent’.

Robert Marston, global head of product at Seacom, said that Microsoft’s decision to locally host cloud services would not only enable it to offer better performance and lower latencies, but it would also critically lower the cost barrier for adoption of these services for enterprise customers.

‘This represents a significant step forward for South Africa’s IT industry because it means organisations can access Microsoft’s rich selection of cloud services from a local data centre,’ he said. ‘This will not only give them more reliability, faster speeds and lower latencies than they can get when accessing cloud services from data centres in Europe or the US, but it will also cut out international connectivity costs, which have typically been a barrier to entry for the move to the cloud.’

It also gives Microsoft an almighty head start in its regional battle with global rival Amazon Web Services (AWS). Speaking to Business Times on the sidelines of the company’s summit in Cape Town in July, Amazon’s chief technology officer Werner Vogels confirmed that it was only a matter of time before AWS opened one of its own data centres in South Africa. AWS was originally built to host Amazon.com, but with the group having subsequently licensed the system to other companies (including Kellogg’s, Unilever, Netflix and, on a more local level, Pick n Pay, Absa and Zapper), it has since grown to become one of Amazon’s most profitable segments, making up about 9% of the company’s US$135 billion annual revenue.

While insisting that the South African and African markets are still in their infancy, Vogels doesn’t believe ‘the winner is going to take the whole market. There will be a handful of global players. I also think there will be niche players that are going to be local’. Either way, the race to supply Africa with much-needed data centres is now well and truly on.