Remember when your watch showed you the time only? Today, your smart watch can record your steps, calorie intake, heart rate and sleep cycles. It can even remind you to drink water or to get up from your desk and walk around at specific intervals. Fitness trackers and other wearable-tech devices were once largely worn to monitor levels of physical activity and track running and cycling routes via GPS. These nifty gadgets are now able to gauge your oxygen levels, monitor changes to your body fat percentages, measure your muscle activity and estimate the number of calories burned during exercise.

A wearable device isn’t just a cool piece of tech to show you are serious about your athletic prowess – it’s constantly collecting valuable data about your behaviour, your vital signs and other health predictors – data that can be put to predictive and preventative use when it comes to your health.

For example, using data (relating to hyper-tension, sleep apnoea and atrial fibrillation) gathered from 14 011 smart-watch users, one mobile-tech company was able to predict with 85% accuracy that 462 users had diabetes. In another study, published in 2019 in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers micro-analysed body-movement data in participants with a wearable gait-measuring device and were able to detect changes in symptoms of Parkinson’s disease successfully.

As wearable tech increasingly plays a vital role in predicting certain diseases by combining vital signs with clinical symptomatology, it is also becoming a key player in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. Because some carriers are asymptomatic, there is always a risk of unknown transmission – and as millions of South Africans return to work after weeks of lockdown, business operations require smart devices to help monitor and manage employee processes and ensure infections are contained.

Behold just one of the many technological weapons – the KC N901 smart helmet. There are a number of temperature-scanning devices available, but this one performs rapid, mass temperature screenings of up to 200 people per minute.

‘The helmet can be used for indoor and outdoor screening, which is important in our country in informal settlements, public transportation hubs, corporates, industrial plants and medical providers,’ says Jeremy Capouya, founder and CEO of local company Granule Holdings, which imports the device.

‘It works on temperature recording and keeps a history of the individuals scanned. It also incorporates AI that makes use of facial recognition and licence-plate recognition. This makes it an efficient and easy device to use for screening at large public areas, busy economic hubs and border controls.’

The technological war against COVID-19 doesn’t end there. According to a May 2020 briefing by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, wearables can help alert people to the possibility of infection by monitoring variations in heart rate or body temperature. As a result, people will know whether to self-isolate or seek medical advice and treatment. Data from wearables can also enhance remote patient monitoring, which takes pressure off healthcare systems and prevents unnecessary exposure of medical professionals to the virus. Data can be used to detect general patterns within a population and identify geographical COVID-19 hotspots.

In early April, South African Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams said government had set up a national tracing database to determine the exposure of persons infected with COVID-19. She also confirmed the industry collectively agreed to provide data-analytic services to facilitate the containment of the virus. The Department of Health is reportedly working with a group of researchers from the University of Cape Town to develop a smart-phone app to help track people who may be unaware they have contracted COVID-19, as well as those who have come into contact with them.

Already named CoviID, this app will collect your location and infection status, and store the data on your phone – not on a centralised government or private-sector database. This will provide you with full authority and control over who gets access to the data, for what purposes and for how long.

On the global stage, archrivals Apple and Alphabet have already launched contact-tracing technology. The Bluetooth-enabled application stores data on people’s phones and when a user tests positive for COVID-19, the system is able to send a notification to anyone who was recently in contact with them.

Even before the pandemic, large insurers and medical aid schemes in South Africa were offering incentives to members who shared health data gleaned from their wearable tech. Experts predict that in future, an insurer or medical aid scheme will be able to calculate the risk profile of a policy holder and provide competitive premiums based on their unique health profile. For the consumer, this can mean anything from customised premiums to health-related savings and promotions, plus early warnings of possible health risks.

Powered by ultra-modern technologies such as AI, big data, cloud computing and machine learning, experts predict that wearable technology could lead to a global healthcare cost saving of about US$200 billion in the next 25 years. However, according to a 2018 Ipsos survey, fewer than 13% of South African households currently own some form of wearable technology. Prohibitive costs, legal regulations and risk of data theft are restraining market growth in South Africa at the moment – but this will change as the technology becomes more affordable, legislation is reviewed and data security improves.

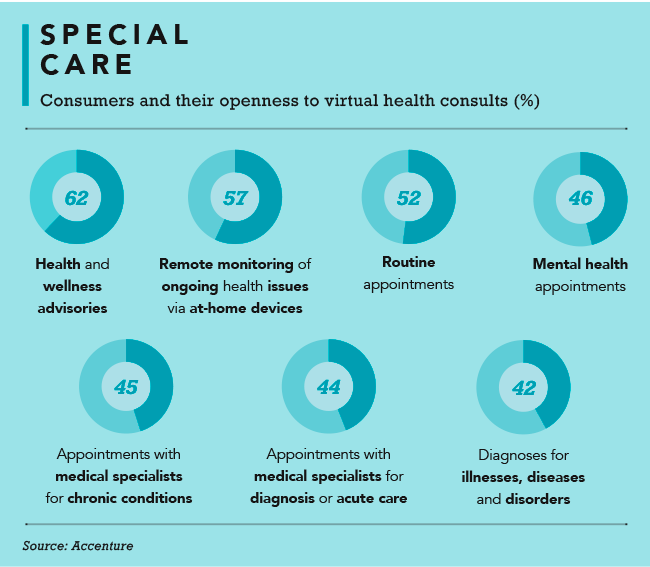

There’s little doubt that personalised data generated from wearables will empower South African doctors and healthcare practitioners to make more informed healthcare decisions in the future but, at present, telemedicine seems to be taking the lead. According to the WHO, 43% of South Africa’s population lives in rural regions, with just one physician responsible for 7 700 people. Limited human resources means telemedicine has the potential to make healthcare far more accessible.

In April this year, the Health Professions Council of South Africa made amendments to allow telemedicine for the COVID-19 lockdown. ‘Telehealth should preferably be practised in circumstances where there is an already established practitioner-patient relationship,’ the guidelines state.

‘Where such a relationship does not exist, practitioners may still consult using telehealth provided that such consultations are done in the best clinical interest of patients.’ Psychologists are now also allowed to use video or telephone calls to counsel new patients.

As South Africa battles to contain the spread of new COVID-19 infections, doctors are increasingly turning to telehealth to help limit the number of patients queueing outside consultation rooms. Experts say that as social distancing is likely to be necessary for the forseeable future, telemedicine will prove invaluable in keeping people away from crowded doctors’ rooms and public transport that might expose them to cross-contamination. Telemedicine saves costs and time for patients, hospitals, medical aids and health insurers because instead of moving staff and equipment, the doctor has access to the patient with minimal costs incurred.

According to the South African Medical Research Council in May, the physical distancing demands of COVID-19 will require capacity to provide healthcare in new ways, delivered remotely, and with the support of mobile phones. Take, for example, a patient with HIV or diabetes, who could receive information on their mobile phone about alternative ways to access their medication. Or a rural health nurse, using her phone to consult with colleagues remotely, on how to deal with a suspected COVID-19 patient. Mobile-phone technology is also key in South Africa’s COVID-19 surveillance response, and 1 500 handsets were distributed to health workers at the start of the outbreak to support tracking efforts.

While technological advances in South African healthcare might not yet have dished up the robot surgeon and the hologram nurse, AI and machine learning are predicted to play a huge role in healthcare segments that rely on the interpretation and processing of images such as X-rays, MRIs or CT scans.

At the University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Intelligent Systems, Qing-Guo Wang is building a database that uses AI. Once the software platform is complete, it will be able produce accurate, immediate breast-cancer diagnoses from an analysis of 20 000 cases from the archives of the Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital.

According to Murray Izzett, business intelligence manager at South African-based company Icon (formerly Medical Specialist Holdings), AI is changing the face of healthcare when it comes to prescriptions. ‘If a doctor is prescribing medication for a patient already on chronic medication from someone else, they run the risk of contraindications or inter-actions,’ he says. ‘With AI, the data is already on file so the doctor can check if the drugs interact and be alerted to any potential issues. The system can also provide them with alternatives so they can assist their patients with the right medications.’

Southern Africa will have to embrace tech to deal effectively not only with COVID-19 but future health issues too. Science and technology are making significant global strides in solving problems. South Africa can use technology to overcome, prosper and thrive; it should be viewed as a positive development – not something to fear.

By Biddi Rorke

Images: Gallo/Getty Images