In the awards universe there’s a prize for nearly everything. It is, however, unusual to get an award for something that you have not made happen. The Averted Disaster Award (ADA) is such an outlier, because it recognises those who prevent or mitigate disasters. In this scenario success means ‘nothing happened’, and therefore the efforts behind the scenes generally go unnoticed precisely because of their success.

In 2024, the ADA winner was announced at the Understanding Risk Global Forum in Japan and, like the runner-up, turned out to be from Africa. The Emergency Operation Centre (EOC) in Lamu County, Kenya, came first for averting at least five major disasters since 2016. Notably, in 2023, it dealt with a compounded humanitarian crisis as a result of severe flooding and a cholera outbreak, followed by the worst drought in four decades. Against the odds, nobody lost their lives in the floods, thanks to the EOC’s early evacuation, resource mobilisation and other effective measures.

Further south on the continent, the ADA’s runner-up prize recognised the Southern Africa Regional Anticipatory Action Working Group (RAAWG) for its concerted effort in not making something happen. In this SADC collaboration – which is supported by the World Food Programme, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation – the emphasis lies on ‘anticipatory’ action. Instead of reacting after a disaster or extreme weather event occurs, anticipatory action is based on risk forecasting and taking proactive measures in advance, before the event can inflict damage to lives and livelihood.

In RAAWG’s case this means that when a forecast threshold for drought is reached, it triggers anticipatory actions such as early warning messages, pre-approved cash transfers, the provision of drought-resistant seeds, agricultural training and improvement of water sources. During the 2023 El Niño, RAAWG reached more than 2 million people in Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, collectively unlocking nearly US$31 million in anticipatory finance.

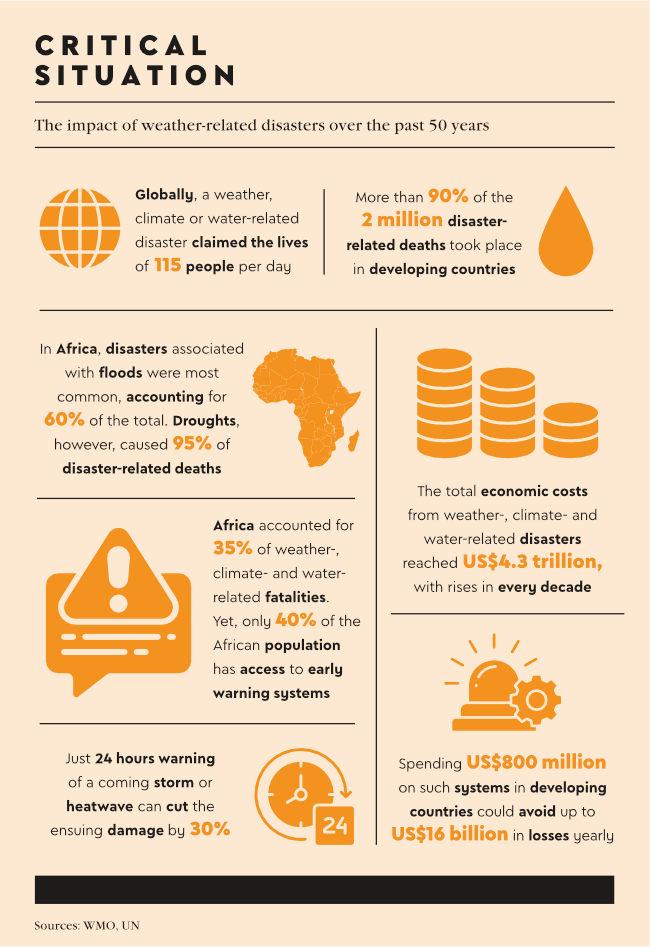

What RAAWG, the Lamu County EOC and other disaster risk-related interventions have in common is their reliance on accurate, timely meteorological data and forecasts. This kind of information will become ever more relevant, as roughly 90% of all natural disasters are related to weather, climate and water, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). Disasters involving hurricanes, floods, droughts, heatwaves or severe storms are increasing in frequency and intensity due to climate change.

‘For most African countries, their national meteorological service is the only agency with a mandate to issue weather warnings,’ says Nico Kroese, research and development manager at the South African Weather Service (SAWS). ‘This puts into perspective the importance of weather services when it comes to issuing early warnings.’

The public often assumes that the weather service’s only job is to provide the daily minimum and maximum temperatures, and information on whether it’s sunscreen or umbrella weather. But as a public entity, SAWS also plays a key role in informing public and private decision-making in matters of health, food security, aviation, marine transport, water resources, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation.

Beyond this, the WMO has named SAWS the regional specialised meteorological centre for Southern Africa, which means extending its meteorological services and expertise to the SADC region.

As part of its public service, SAWS provides a free WeatherSMART app, which stands for ‘Safe, More informed, Alert, Resilient and having Timely access to relevant information and services’. The app provides real-time local weather updates, forecasts and severe weather alerts to help users in South Africa prepare and manage the impacts of weather. Users can set preferences for receiving specific types of weather alerts based on their location and needs.

‘We utilise a variety of communication platforms to reach the masses, including mobile phones, where we distinguish between basic feature phones and smartphones, to ensure we produce an app that allows everybody to access our weather warnings,’ says Kroese. ‘It doesn’t help if we sit with the information in the weather office and can’t disseminate it to the communities that actually require it to act upon.

‘To extend our reach, we also collaborate with intermediary organisations, such as the disaster management structures on national, provincial and local government levels, the Red Cross and others that assist people in emergency situations.’

Given that three out of four people worldwide have mobile phones, it is outrageous that only half of the world has systems to warn them of disaster, says the WMO. In Africa, 60% of the population is not covered by any early warning systems, despite living in one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to climate extremes. That’s why the UN launched its Early Warnings for All initiative that aims to have everybody across the globe covered by an effective early warning system by 2027.

Early warnings are the low-hanging fruit to save lives and livelihoods before a disaster unfolds. A widely quoted report by the Global Commission on Adaptation says that early warning systems provide more than a tenfold return on investment. Just 24 hours’ notice of an impending hazardous event can cut the ensuing damage by 30%, states the report. And spending just US$800 million on such systems in developing countries would avoid losses of US$3 billion to US$16 billion per year.

In fact, more accurate early warnings and better co-ordinated disaster management have decreased the number of lives lost almost three-fold in the past 50 years, according to the commission. Yet the economic losses have gone up seven-fold during this period, from an average of US$49 million to US$383 million per day globally. Storms caused the largest economic losses around the globe.

In Southern Africa, two of the most destructive weather events were Cyclone Idai (2019), responsible for more than 1 300 deaths in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi, and Cyclone Freddy (2023), which killed more than 858 people in Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi.

While early warnings were able to save many people, those who perished possibly didn’t receive a warning, or underestimated the scale and intensity of the storms, or simply couldn’t protect themselves.

Kroese is involved in the Early Warnings for Southern Africa (EWSA) project to transform access to early weather warning systems for urban communities in South Africa, Zambia and Mozambique. As part of the Weather and Climate Information Services (WISER) Africa programme led by the National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the UK’s University of Leeds, EWSA uses ‘nowcasting’ – a process whereby real-time satellite images over Africa are used to predict weather conditions over the next six hours. In contrast, short-term forecasting uses numerical models to predict the weather for the next one to three days, while medium-term forecasts look at the next 10 days.

‘Typically, nowcasting focuses on the first zero to two hours, but in the WISER-EWSA context, we’re trying to stretch this to six hours ahead,’ says Kroese. ‘Therefore, the tools for these warnings are quite different from developing the forecast for tomorrow. In nowcasting, we utilise weather radar to get an immediate perspective of what’s going on at the moment. We then extrapolate those observations to the next one or two hours, and do the same with satellite information. Satellites are an excellent tool within the nowcasting timescale. Real-time reporting weather stations are also of big importance to monitor the weather and verify whether our forecast, nowcast or warning is actually happening.’

Over time, the wider SADC region may benefit if EWSA’s nowcasting techniques are to be scaled. ‘This project has a strong focus on engaging with communities and stakeholders to ensure we develop products and services that are actually relevant to them,’ says Kroese. ‘As academics and forecasters, we talk in a certain language that the end user might not fully comprehend. Hence, it’s a capacity-building exercise for the communities as well, to understand the alert and learn what actions to take once a warning has been issued.’

Especially in nowcasting, Kroese says AI is assisting the forecasters in providing improved forecasts to save lives and property.

Ironically, the better Africa’s weather forecasts and early warnings become, the better prepared we’ll be to manage the impacts of storms, floods and drought – but the less we’ll hear about the work behind the scenes, because an averted disaster means ‘nothing happened’.