‘Has the time not arrived for us to be bold and reach beyond ourselves and do what may seem impossible? Has the time not arrived to build a new smart city founded on the technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution? I would like to invite South Africans to begin imaging this prospect.’

It’s been five years since Cyril Ramaphosa, President of South Africa, first spoke about building a smart city from the ground up in his 2019 State of the Nation Address (SONA).

He mentioned smart cities again (as well as bullet trains) in his 2020 SONA. And in December last year, when questioned about the progress of these plans, said that ‘I invited South Africans to look beyond the challenges of the present and to imagine a country of high-speed trains, smart cities and a high-tech economy. I said that to reinvigorate the implementation of the National Development Plan, we must cast our sights on the broadest of horizons. This bolder vision of a technologically advanced society has received practical attention over the last few years’.

The smart city he was referring to is the Lanseria project outside Johannesburg, which aims to be home to between 350 000 and 500 000 people by 2030 as well as contain commercial and industrial buildings. However, for the past five years progress has been patchy. For instance, in February last year the Mail & Guardian newspaper reported that ‘the land earmarked for the Lanseria urban development remains just veld’.

In February this year, the Sunday World newspaper reported that Vincent Magwenya, Ramaphosa’s spokesperson, had replied to a series of questions sent to the Presidency concerning the Lanseria project. ‘The Greater Lanseria master planning process for the new smart city, which will ultimately be home to over 3.5 million people, was completed in December 2020. This included consultative webinars with property developers or large landowners, waste/water/electricity infrastructure experts. […] Also roads and transport networks, human settlements, social infrastructure leads and ICT experts,’ the paper quoted Magwenya as saying.

‘The city is not to be an assembly of private, gated developments. Instead it will be assembled according to the principles of perimeter-block development. Generally, four-, six- and eight-storey buildings stretch around the street block’s outer perimeter. They are looking both out onto the street and inward onto the internal courtyard. These interior courtyards will be more personal and semi-private to those people inhabiting the block; and are to form inner parking lots, gardens and play lots.’

The newspaper quoted Magwenya as saying that ‘the municipal bulk infrastructure required for the LSC [Lanseria Smart City] was costed at about ZAR15 billion’.

Sunday World said the Gauteng Growth and Development Agency and the Infrastructure Fund ‘are working closely to explore alternative financing options’ to fund the required municipal bulk infrastructure.

At its core, a smart city leverages digital technology and data-driven insights to enhance the efficiency of urban services, improve the quality of life for residents and foster sustainable development. These cities integrate various facets of technology, such as IoT, AI and data analytics to optimise resource utilisation, streamline governance and enhance citizen engagement.

The advent of smart cities heralds a plethora of benefits. Firstly, improved infrastructure and utilities fostered by smart city initiatives promise to enhance the quality of life. From efficient transportation systems to reliable energy grids and advanced healthcare facilities, citizens stand to benefit from enhanced accessibility and reliability of essential services.

Moreover, smart cities prioritise sustainability, thereby mitigating environmental degradation and promoting healthier living environments. Through initiatives such as renewable energy integration, waste-management optimisation and green space development, smart cities contribute to reducing pollution levels and enhancing public health outcomes.

Smart city technologies also empower citizens by fostering greater connectivity and access to information. With initiatives such as digital inclusion programmes and smart governance platforms, citizens can actively participate in decision-making processes, hold authorities accountable and contribute to the overall development agenda.

In addition, smart cities prioritise safety and security through the deployment of advanced surveillance systems, emergency response mechanisms and predictive analytics. Beyond the benefits to individual citizens, smart cities attract investment and spur innovation by creating conducive ecosystems for technology start-ups and entrepreneurs. Moreover, the efficiency gains facilitated by smart city initiatives translate into tangible economic benefits. By optimising resource utilisation, streamlining logistics and reducing operational costs, businesses operating within smart cities can enhance their competitiveness and productivity.

The data-driven nature of smart cities facilitates evidence-based decision-making and policy formulation, thereby enhancing governance effectiveness and fostering economic stability. By leveraging real-time data insights, policymakers can identify areas for intervention, allocate resources efficiently and monitor the impact of policies in real-time.

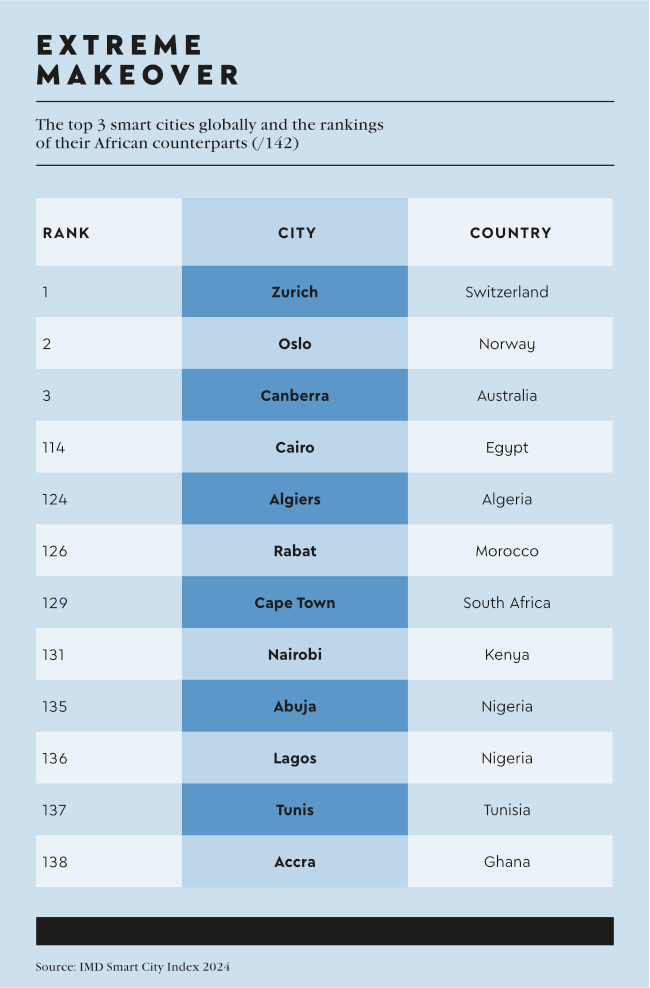

Those are the good points… Alas, many African city authorities are struggling to even provide basic services such as refuse removal and potable water. Urgent funding is needed for infrastructure such as roads and sanitation, not to mention housing to cope with increased urbanisation. Only a handful of major African cities – Algiers, Cairo, Cape Town, Tunis, Accra, Nairobi, Lagos, Abuja and Rabat – are included in the 2024 IMD Smart City Index, which ranks 142 global cities according to economic, technological and other criteria, including quality of life and the physical environment. Although that’s an increase over the 2023 index when there were only five African cities, none ranks higher than 114 (Cairo).

The big hurdles to further advancement are, firstly, the digital divide. This poses a significant barrier to inclusive smart city development, as disparities in access to technology in Africa and digital illiteracy persist across the continent. Bridging this gap requires concerted efforts to ensure equitable access to digital infrastructure and technology education, particularly in underserved communities.

Then there’s the issue pertaining to data privacy, which will necessitate robust regulatory frameworks and investments in cybersecurity infrastructure. Safeguarding citizen data and critical infrastructure from cyberthreats is paramount to maintaining trust in smart city initiatives and fostering their long-term sustainability.

However, it’s the financing of smart city projects that remains the biggest challenge. Addressing this requires innovative financing mechanisms, such as public-private partnerships, development assistance and impact investment to mobilise the necessary capital for smart city development. All will need massive political vision and will to progress further than the drawing board.

‘The smart city vision, which is presented as the solution to South African challenges, is one of high-speed rail, glossy new buildings and cities, and fast technology. This tech-obsessed approach has led many South Africans to question the value of the smart city in comparison to the country’s pressing challenges, such as the housing crisis, water shortages and the widening poverty gap,’ was how the South African Cities Network, a think tank, encapsulated the issue in a 2020 paper examining the smart city concept.

‘Compounding the scepticism about smart cities is the fact that South African cities have different approaches to engaging with the smart city concept. Therefore, before examining smart city issues and projects, it is essential to understand the role of smart cities in a South African context, given that cities, literature, legislation and policy have not defined this understanding.’

In October last year Nancy Odendaal delivered a lecture at the University of Cape Town titled Reframing African Smart Urbanism. ‘We must differentiate African cities from the broader smart city narrative, as the context and challenges are unique,’ she said.

Odendaal added that ‘true transformation through technology lies in empowering individuals in their daily lives’. She highlighted the role of technology in everyday decision-making for disadvantaged communities, and highlighted several specific themes, ‘including the power of disruptive platforms such as ride-hailing and food delivery apps to boost informal economies in Africa’.

Perhaps the best way for Africa to learn is to tap into the experience of other countries that have learnt the smart city lessons the hard way. Singapore, for example. In 2019, the inaugural IMD Smart City Index ranked it no 1 in the world (it was no 5 in the 2024 list).

In August last year ITWeb interviewed Rahul Ghosh, director of Enterprise Singapore for Middle East and Africa, when he was part of a government visit to South Africa. Enterprise Singapore is a component of Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry.

In 2014 Singapore launched its Smart Nation initiative to create a country driven by technology and digital innovation. Ghosh told the website that Singapore ‘has learnt that starting small’ is important. ‘South Africa has on its plans some smart city developments and we’ve been in discussions with the different parties related to that. It doesn’t need to start at the city level; it can start at a small municipality level, at an estate level, or even just start with smart building.’

He said a country could begin its smart city journey by deploying sustainable and resource-efficient technologies and solutions. ‘For example, this can start at a municipal level with solutions that are able to detect water leakages. There can also be deployment of smart street lamps, which won’t only provide light but also be used to capture data for traffic. There also needs to be provision of WiFi solutions, especially where there’s no WiFi or internet connectivity through fibre.’

According to Ghosh, it’s very important to establish policy regulation frameworks. ‘Some of these smart city solutions are getting into the personal space of citizens, so there must be discussions in terms of getting the necessary regulations and specific frameworks in place as the smart city projects are being rolled out.

‘When everything starts to fall in place, then it’s like a symphony orchestra… Every part needs to work.’