COVID-19 spread through Africa this year as it has the rest of the world, with no country on the continent left unscathed. The prognosis was initially dire, given the lack of resources, already strained health systems, and difficulties regarding hand-washing with limited access to water, social distancing in crowded townships, and communicating with remote rural populations. And that’s aside from the prevalence of malaria and TB, and the growing incidence of diabetes and other comorbidities known to raise susceptibility to COVID-19.

Yet the death rate has not matched early fears. South Africa, for instance, has the highest number of COVID-19 cases on the continent – close to 704 000 in late October, the 12th highest globally – yet the death rate that the modelling consortium advising the government estimated would reach 48 000 by November had not emerged, with a little more than 18 470 deaths recorded.

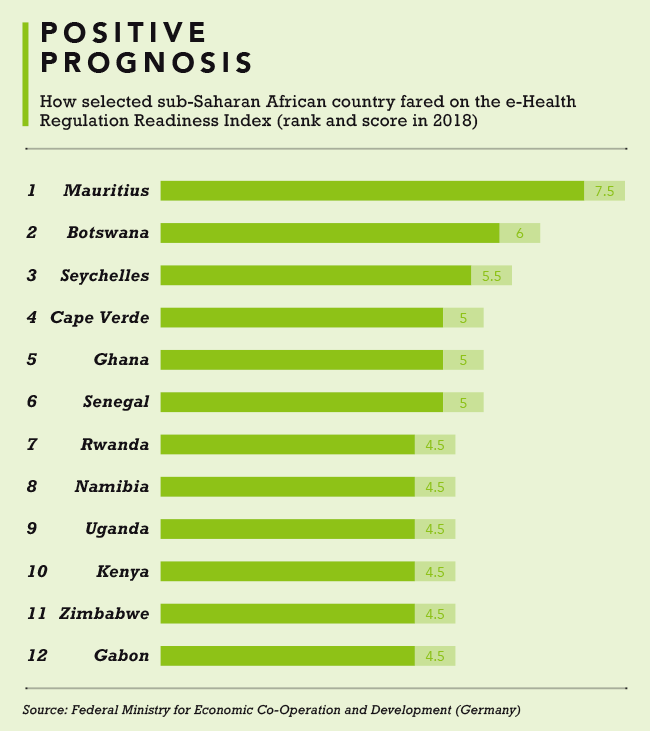

While the reasons for Africa’s apparent ‘great escape’ are the subject of great conjecture, ranging from its youthful population to early-childhood vaccines, one factor being credited is the speed and efficiency with which e-health solutions have been rolled out to fill the massive gap in conventional healthcare. The WHO has been urging countries to maximise the use of e-health since 2018, when director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus addressed the Second International Conference of Ministers of Health and Ministers for Digital Technical Technology on Health Security in Africa. He stressed that electronic health records and the use of smartphones and smart watches, electronic medical prescriptions, AI, e-learning and other digital tech could play a vital role in raising awareness of health issues, enabling patients, and training and empowering healthcare professionals. Ghebreyesus said he was ‘happy to see that the African continent is making remarkable progress in these areas’.

Before the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Africa was announced (in Egypt in February), the tech-innovation landscape on the continent was limited, and centred mainly on the financial sector. The health sector was seen as unappealing to investors out to make money, notes the Lancet. In 2019, however, a Disrupt Africa report on tech start-up funding already showed an uptick in funding, with Nigeria and Kenya, the top investment destinations, drawing US$149 million and US$122 million respectively. ‘The number of investors in African tech start-ups jumped by 61% to reach 261%,’ a press release for the report notes.

In those countries and across Africa, the pandemic gave e-health a colossal kickstart. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country with the biggest economy, but estimated by the WHO to have just four doctors per 10 000 patients, the country’s Centre for Disease Control was soon overwhelmed by calls from panicked citizens seeking reliable information. It quickly moved to expand its call-centre service capacity with iQube Labs’ locally developed My Service Agent – an AI-interactive voice-response system originally designed for bank call centres – capable of communicating with thousands of callers at once and dispensing accurate information.

Then, as cases ramped up and testing became critical, Disrupt Africa reported that Nigerian e-health start-up 54gene had partnered with the Ogun State government and First City Monument Bank to create the country’s first COVID mobile testing lab, with plug-and-play features that obviated the need to ship samples elsewhere for processing, and reduce the waiting time for test results.

A slew of other e-health interventions followed, such as the Wellvis COVID-19 triage app, which enables people to assess their risk of infection by answering questions linked to known symptoms; and GloEpid, a smart bot that allows them to do self-assessment and advises them on their COVID-19 exposure risk, sparing them the visit to a crowded local health facility. GloEpid now also does contact tracing, using Bluetooth and GPS location tech.

In South Africa, e-health measures were put in place early, using lessons learnt in the prevention of TB, HIV and listeriosis, and concerns over the possible spread of Ebola. The Department of Health set up an emergency operations centre at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) six years ago to co-ordinate and direct outbreak responses, equipping it with banks of computers, screens and real-time tracking and mapping ability. ‘We’re using mobile networks to track and trace people and define hot spots to model and contain outbreaks,’ Lynn Morris, interim executive director of the NICD, told the Lancet as COVID-19 bit this year. By April the Health Professions Council of South Africa had amended its guidelines to permit doctors and therapists to use video or phone calls to treat patients via telemedicine.

Independent e-health players have joined the party, led by the likes of Vula Mobile, whose app won the Sentech Best Health Solution Award at the 2019 MTN Business App of the Year event. It was developed by ophthalmologist William Mapham, after he worked at the only cataract-removal eye clinic in eSwatini and witnessed the great distances people had to travel for help at overburdened facilities. ‘I saw how a mobile phone could be used to improve eye care in a rural public health setting,’ he says.

As of late September, Vula Mobile had provided access to more than 4 000 doctors and 19 000 patients a month, covering specialties from ophthalmology to orthopaedics, cardiology, burns, family medicine, HIV/Aids and, this year, COVID-19. It’s been instrumental in the national Doctors-on-Call hotline, where some 450 medical doctors have made themselves available for South Africans to phone in and speak about the virus. Calls are documented and reports generated using the app, which simultaneously captures referrals to the NICD for testing and results.

A doctor in a rural area confronting a difficult case would often call someone or send them a picture on WhatsApp asking advice, says Mapham. With the Vula Mobile app, the doctor follows the referral workflow developed for each specialty. They complete a questionnaire about the patient and, where applicable, a test, and take photographs, which the system sends to the on-call specialist for evaluation. It’s directed not to a random doctor but one assigned to those specific types of questions. From the specialists’ side, instead of getting a call requesting advice, they receive a digital pack of information, including images, a test result and the patient’s history, presented in a way that lets them respond fast. ‘The average response time from a specialist is about 15 minutes,’ says Mapham.

The pandemic is also showing, in an unprecedented way, the advantages major established health-tech companies provide by digitalising and integrating systems within and between health facilities.

‘With fast and easy data sharing, our eHealth Solutions fosters collaboration among healthcare providers,’ reports Siemens Healthineers, which connects isolated data from different healthcare providers. Additional applications enable care teams to deliver ‘co-operative care’ via mobile, web-based and complete infrastructure workflow solutions, including an e-health physician portal, patient portal, patient referral, teleconsultations and second opinions, and e-health conferences.

Meditech is a global corporate with headquarters in the US. ‘We’re an integrated health-care systems platform automating everything within the healthcare ecosystem,’ says Sushanth Pillai, MD of Meditech South Africa. ‘Some 90% of private labs in SA now run on our system, including Lancet, Ampath and PathCare. That means during the COVID crisis, if one lab is inundated with tests, as happened early, it can push the excess to another lab through interoperability. We were also able to help the Botswana Ministry of Health set up border health sites, using Meditech to request incoming foreigners to do tests and send them to hospitals if further evaluation was required. And from very early we looked at building a contact-tracing app for hospitals and community outreach groups.’

Their systems are now in a number of public hospitals across South Africa, says Pillai. ‘Data in South Africa is still largely paper based, and the transfer to digital format makes it instantly and widely accessible and easily updated. This applies to patient records and sharing of information and experiences – invaluable with COVID, which has evolved constantly with different strains and treatment protocols. In hospitals where Meditech was being used, we saw a greater degree of agility from healthcare providers to help patients and institute proactive measures to combat the pandemic.’

With 38 years in South Africa, Meditech is now in 15 African countries, with Botswana its showpiece of how e-health systems can work: ‘The entire country of 2 million people […] is on a single Integrated Patient Management System powered by Meditech, all hospitals and labs are connected. Wherever a patient checks in, with COVID or anything else, their records from womb to tomb are presented – whoever sees you knows your history and can make a much more informed assessment of your condition.’

Like many in e-health, Pillai believes the sector will leverage its COVID-19 boost post-pandemic. ‘In South Africa, where National Health Insurance is set to be introduced, it will be vital to have interconnectivity between hospitals so they can talk to one another – they don’t at present, and patients who go to several different hospitals have to redo tests. a lot will rest on having a converged digital-health system.’

E-health start-ups across Africa also appear upbeat about the future. Henry Mascot, co-founder and CEO of Nigeria’s Curacel, which began by helping clinics convert paper files to digital and manage their data, appointments and billing, is now assisting insurance firms to achieve rapid claims management and accurate payouts. The way he sees it, ‘many people in Africa who previously didn’t take healthcare seriously will start taking their health a lot more seriously, and this will drive up healthcare consumption. Government will increase budgets for healthcare, and this should trickle down into the space. Hopefully investors will give this space a lot more attention as well’.

Challenges remain, including finding business models that provide remote consultations cheaply enough to be rolled out over big parts of Africa, and models for low-cost delivery of critical medication. But COVID-19 has provided a watershed moment for them to be addressed, and for e-health to take off.