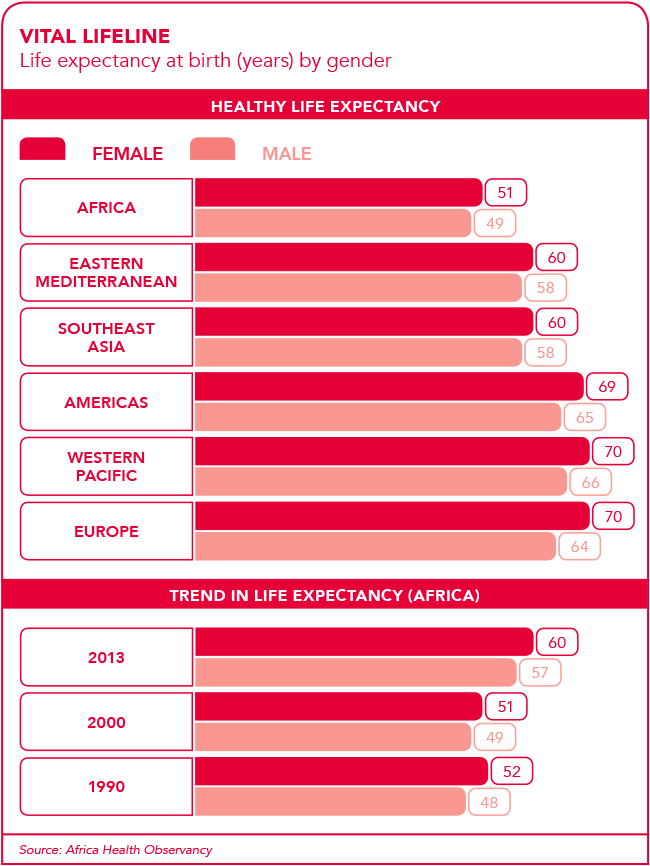

There’s an unhealthy imbalance in the global healthcare sector, and it’s killing millions of Africans. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 11% of the world’s population yet, according to UN research, the region carries 24% of the world’s disease burden, it is home to just 3% of the global healthcare workforce, and it spends less than 1% of the world’s financial resources on health.

It’s a huge gap but a new report published by the Lancet Commission claims that it can be closed within a generation if Africa seizes the opportunities afforded by a rapidly growing workforce, and if health systems are transformed to target the needs of individual countries and communities.

The report was authored by more than 20 African policy-makers, academics, clinicians and entrepreneurs, and was launched at the African Population and Health Research Centre in Nairobi in September. In a press statement ahead of the event, co-author Bright Simons said: ‘By adopting more advanced but appropriate technologies rather than following slow, classic paths to address health workforce constraints and improve people’s access to quality health services, African countries can realise the potential to leapfrog opportunities for health in Africa, sometimes in world-leading ways.’

Simons is a co-founder of mPedigree, a Ghanaian-based mobile app that helps identify counterfeit medicines. Sproxil, launched by another of mPedigree’s founders, Ashifi Gogo, does similar work. Both services are active in several countries across Africa, and both serve an absolutely vital function.

Substandard, spurious, falsely labelled, falsified and counterfeit (SSFFC) medical products pose an enormous public-health risk, with about 10% of the medications available worldwide and 25% of those in less developed countries estimated to be counterfeit. Frighteningly, the WHO warns that ‘falsified medical products may contain no active ingredient, the wrong active ingredient or the wrong amount of the correct active ingredient’, with many containing useless ingredients such as corn starch, potato starch and chalk.

Sproxil offers a simple, tech-driven solution. A scratch-panel sticker is attached to the packaging of legitimate drugs. Customers scratch off the panel to reveal a code, and then text message the code (free of charge) to Sproxil, which checks the code against its database, and then texts back confirmation of authenticity. If the code is fraudulent, the user is then connected to a helpline that collects further information, and facilitates follow-up from local authorities responsible for tracking and eliminating counterfeiting activities. More than 70 pharmaceutical firms (including global heavyweights such as GlaxoSmithKline) have signed up for the programme.

Sproxil and mPedigree are testament that, when it comes to healthcare in Africa, innovation does not have to mean invention. Their solutions use simple technology to solve real-life problems.

Ugandan social enterprise, the Medical Concierge Group (TMCG), gives users free access to healthcare professionals and health information using the existing communication technology platforms that they’re already accessing, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype, text messages and voice calls.

Ugandan social enterprise, the Medical Concierge Group (TMCG), gives users free access to healthcare professionals and health information using the existing communication technology platforms that they’re already accessing, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype, text messages and voice calls.

TMCG’s more than 50 000 monthly users mainly fall into the 18- to 35-year-old tech-savvy demographic. ‘They are very comfortable speaking to the doctor in this way,’ co-founder Dr Davis Musinguzi told AllAfrica.com.

‘Seventy percent of the calls are for primary healthcare consultations and picking stuff up from the pharmacy; 20% to 25% need to see a specialist like a cardiologist or an obstetrician; 1% to 5% need to go directly to a health facility.’

Increasingly, Africa’s healthcare innovators have focused on the last-mile access that connects people to the healthcare products and services they need.

In Lesotho, an enterprise called Riders for Health has been providing that access for more than a decade through its national motorcycle fleet. Before Riders launched this service, it would often take people living in remote, rural areas as long as three months to receive HIV-test results. Today the waiting period is down to less than a week.

However, motorcycles are old-school compared to the high-tech medical courier service offered by Zipline in Rwanda. Like Lesotho, Rwanda is a mountainous country, but barely a quarter of its 4 700 km of roads are paved – forcing Zipline to employ a fleet of aerial drones to deliver blood-transfusion packages.

The company launched in 2016, and has already expanded its services into neighbouring Tanzania, where just 8% of the roads are paved. It doesn’t solve the underlying infrastructure problem but it does deliver a life-saving service to hard-to-reach parts of the country.

‘Patients in non-urban areas sometimes have to travel hundreds of kilometres to access medical facilities – often resulting in progression of the illness or the demise of the patient,’ Vino Govender, executive for product innovation and marketing at Dark Fibre Africa (DFA) wrote in a recent statement.

‘This is where technologies based on resilient and high-speed data connectivity can assist significantly in reducing and even eliminating the “distance barrier” to specialised health and medical care services.

‘For example, the deployment of video solutions can easily connect patients at family-health clinics to specialists in larger medical centres – meaning that children could potentially consult a doctor whose practice is hours away without travelling the distance.’

DFA, with its open-access fibre infrastructure deployment, is helping connectivity service providers deliver a range of high-speed fixed and wireless connectivity services through which specialised healthcare and medical services can be delivered to remote communities. This telemedicine approach is gaining traction across Africa as broadband connectivity becomes more and more of an on-the-ground reality.

‘Botswana boasts one of the most secure economies in Africa but deadly diseases undermine that stability,’ Amr Kamel, GM of Microsoft (West, East, Central Africa and Indian Ocean Islands), wrote in a recent opinion piece. ‘These diseases are easily preventable with the right skills and resources, but a large part of the country’s population is rural, and the doctors who can diagnose them and provide specialised healthcare are difficult to access.’ To get around this, Kamel wrote, Microsoft and the Botswana Innovation Hub launched Africa’s first telemedicine service, harnessing the power of TV white spaces – the unused frequencies in the TV spectrum – for broadband connectivity. ‘Now health personnel can conduct consultations to patients in the most remote areas via Skype for Business,’ he wrote. ‘Doctors can also access high-resolution pictures on the cloud, meaning they can “examine” the patient in real time, regardless of where the patient is, and make a diagnosis and prescribe treatment straight away.’

That idea of using tech to bring healthcare to the patient – and not making the patient travel for miles or wait for hours to receive treatment – was the driving idea behind ‘pharmacy of the future’, which is based on the bank ATM system. After registering for the service, the patient is given a card that they insert into a self-service ATM-like machine (called a pharmacy dispensing unit, or PDU). They then enter a PIN and select the medication they require from the prescription list. The PDU immediately and automatically dispenses the medication. It’s quick, it’s convenient and it comes with qualified medical support – the PDU allows patients to communicate directly with a trained pharmacist via the machine’s built-in video-conferencing function.

The innovation recently won the German Global Health Award at the B20 Global Health Conference in Berlin, and is now being piloted at various community clinics and shopping centres by the Gauteng Department of Health.

The South African Ministry of Health announced the pilot programme at the 21st International Aids Conference, which took place in Durban in mid-2016. There, Minister of Health Aaron Motsoaledi told delegates that the number of South African patients covered by the national HIV-treatment programme had increased over the past three decades from 400 000 to more than 3.4 million. He added, however, that ‘the number of healthcare workers has not kept up with this increase, often leading to frustrated patients and lack of treatment adherence. The biggest challenge with not adhering to treatment is that it poses a real risk of the emergence of drug-resistant HIV, in the same way drug-resistant TB came about. It is thus imperative that we embrace all available measures to make it easy for people to continue with their treatment’.

The PDU is certainly a major step towards achieving that goal, but it’s merely one solution. Other innovations – from delivery drones to couriers on motorbikes; counterfeit-checking tech to advanced telemedicine – will also be increasingly called upon as Africa continues to close its healthcare gaps.