The COVID-19 pandemic has catalysed exceptional innovation in the health sector, with global collaboration occurring on an unprecedented scale between leaders in academia, government, business and healthcare. Vaccine approvals and roll-out have been the fastest in human history. There has been a rapid uptake of technology that connects patients with health practitioners, and the surge of insights generated in pursuit of a cure may well hold the key for treating formerly intractable disease such as HIV, cancer, malaria and multiple sclerosis – not to mention, preparing for future pandemics.

Central to all of this is data. Big data to be exact. In fact, so critical is this ‘new oil’ – so dubbed due to its value in the digital economy – to the world’s preparedness for future pandemics, that the WHO is reportedly considering an emergency data-sharing contract that would allow researchers to move information across borders more easily in global health crises, and science academies of the G7 nations have called to increase ‘data readiness’ for future health emergencies.

But what does ‘data readiness’ look like, and how can Africa leverage this increasingly valuable resource in the service of future pandemic preparedness?

‘Big data’ is useless unless it can be strategically processed. Although the pandemic radically accelerated the use of technology and digital tools in the health sector – and, concomitantly, the collection of data – it’s the processing, analysis and application of this data that really counts, which is anything but straightforward. ‘The production of data continues to grow rapidly, but the ability to analyse and draw insights from it has been hampered by the slow adoption of digital technologies, by inconsistencies in data types and definitions, by restrictions on access to the data held by public agencies and private businesses, and by political differences between nations,’ according to the G7 ‘data readiness’ statement.

The key? Artificial Intelligence. For instance, with the right data, AI can help researchers to discover how quickly a virus is spreading, in which areas, and the specific vulnerabilities of these areas. AI can assist with the collection and management of individual health data, help to pinpoint disease patterns, and can play a significant role in formulating vaccines and treatments.

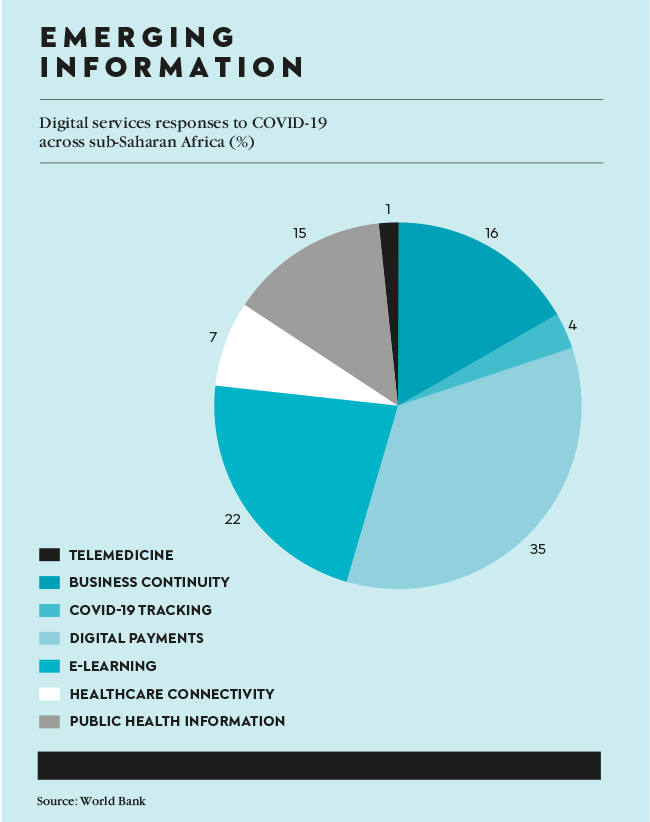

While Africa’s health systems, in relative terms, are not as robust as developed regions, it was not hit as hard by the pandemic as other territories. In addition, the continent is undeniably experiencing a digital revolution (it’s been said that it’s easier to get access to a mobile phone than clean drinking water), with an estimated 900 million mobile-phone subscriptions. For this reason, most African nations are well positioned to collect, analyse and share data with their neighbours, to leverage AI technologies, and to devise effective policies and response strategies.

And it is particularly urgent that Africa strengthens its capacity to respond to possible outbreaks. According to Kariuki Njenga, a Kenyan virologist at the Kenya Medical Research Centre working to prepare the continent for the next pandemic, the likelihood that Africa will be the source of the next pandemic is high. ‘Diseases that come from wildlife account for more than 65% of all emerging infectious diseases,’ he tells science journal Nature. ‘Although the COVID-19 pandemic did not originate in Africa, our region is a hotspot for emerging infectious diseases because of the range of wildlife and the number of human-wildlife interactions.’

There is much work to be done, not only in terms of strengthening countries’ capacity for diagnostics and vaccines, and establishing emerging-infectious-diseases centres, but also harnessing AI in the service of processing essential data. A paper published by African WHO researchers in November 2021 identified several priorities for the deployment of AI in Africa. ‘Data protection, privacy and sharing protocols; training and creating platforms for researchers; funding and business models; developing frameworks for assessing and implementing AI; organising forums and conferences on AI; and instituting regulations, governance and ethical guidelines for AI.’

Several countries are making strides in this regard. Nigeria experienced a ‘mild’ pandemic outcome compared to the global trend – however, it’s been suggested this may be because of insufficient data collection. Epidemiologist Chikwe Ihekweazu, former director-general of the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) until October 2020, now head of the WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence, says that ‘the COVID-19 pandemic response was really the first time in recent years that the Nigerian government introduced a whole-of-government approach in response to a disease outbreak. While we responded to the 2014 Ebola outbreak with a similar approach, the pandemic was on a much larger scale and a presidential task force was set up’.

Prior to the pandemic, he says, the NCDC worked at a sub-national level to gradually introduce the Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS). This is a digital platform based on the WHO-recommended Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response to collect data from health facilities. ‘During the pandemic, we had to rapidly roll out its use to cover all 36 states, plus one federal capital territory, in Nigeria. The data collected through SORMAS helped us advise the presidential task force in making important decisions, such as introducing or lifting lockdown measures. However, this was limited as we could not make some countrywide decisions based on data from the health sector alone.’

In preparing for future pandemics, Ihekweazu stresses the need to look beyond data from the health sector, to introduce approaches that collect and use data from other sectors that also affect public health, for example the environmental sector, to understand the impact of climate change on the risks for future pandemics. ‘We must remember that zoonotic diseases are often causes of local outbreaks and pandemics, and so we need collaborative approaches that enable the collection, integration, joint review and use of data from animal and human health sectors.’

In Rwanda, a visiting professor at Carnegie Mellon University Africa, Patrick McSharry, is collaborating with the Rwandan government on a project that aggregates data into a visual representation in the form of a dashboard that graphically displays positive cases, deaths, vaccinations, COVID-19 tests and much more. The dashboard has a predictive element that uses statistical evaluation to select the most appropriate of a variety of epidemiological forecast models. The tool is still in the testing phase but hopes are high that it will soon be available to help the Rwandan government make informed policy decisions, and eventually be scaled to aggregate pandemic data throughout Africa.

South Africa, the most technologically advanced country on the continent, ‘has a long history of excellent research and surveillance for infectious disease,’ says Waasila Jassat, professor and public health specialist at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) of South Africa.

‘When the pandemic began, many researchers and institutions pivoted to support the COVID response. We established excellent surveillance systems for testing and case data, hospitalisation, genomic surveillance, excess mortality, wastewater; we continued and supplemented that with a few key research projects that tried to addressed remaining important questions to better understand SARS-CoV-2, including studies on viral transmission dynamics, serosurveillance [the testing of blood samples for the presence of antibodies against a particular disease], prevalence and risk factors for long COVID, and the many neutralisation studies that better characterised vaccine effectiveness against new variants.

‘Key to these efforts were their collaborative nature, with many institutions working together to share data and combine efforts at modelling, analysis and interpretation of the rich data that was being produced. Another important aspect was the data linkage between different surveillance systems that allowed us to quickly respond with useful insights. South Africa is in a good position to institutionalise many of these surveillance systems to support routine monitoring as well as pandemic preparedness.’

Recently, the first medical-data sharing hub was launched in South Africa. CareConnect, founded by six of the country’s largest private healthcare organisations, (Discovery Health, Life Healthcare, Mediclinic, Medscheme, Momentum Health and Netcare), is a Health Information Exchange (HIE) that will enable the integration of healthcare data from various sources to provide a single online entry point for healthcare providers and funders to access relevant patient information.

‘There is no question that much of the innovation in the health sector, globally, is being driven by digitisation, data and tech,’ says CareConnect founding CEO Burnett Biddulph . ‘From advances in accessing patient information through electronic medical records, to wearables that monitor and connect patients to their healthcare data, to telehealth consultations, which have the potential to revolutionise access to care. The CareConnect HIE promises to usher in a new paradigm to South Africa’s health system, one that paves the way towards global trends of co-ordination of care, value-based care models and the move to greater access, quality and efficiencies in healthcare,’ he says.

‘With more than 3 million lives already secured on the HIE under Phase 1A, and UAT [user acceptance testing] in progress for Phase 1B, we are now hard at work at ensuring that the data in the HIE is of high quality and robust enough to allow for all current use cases and future use cases that will be required.’

It’s clear that most African nations understand the essential role of robust data management strategies in preparing for future pandemics – experts assure us, they are on their way – which means the race is on to plug the technological and systemic gaps in African nations’ emergency health response protocols.