African nations are among the most uninsured and underinsured in the world, but the industry has evolved significantly as growth opportunities in these markets have outstripped those in developed nations.

The continent provides a lucrative market for insurers as traditional insurance penetration remains low due to product complexity, high premiums and a lack of accessibility. This also involves hurdles in reaching consumers to educate them about the value of insurance, which products are relevant to them, and, should this succeed, collecting premiums and claim submissions.

Before COVID-19, McKinsey predicted the African insurance market would grow at around 7% per year between 2020 and 2025, nearly twice as fast as North America and three times faster than Europe.

At about 14%, South Africa has the highest insurance-penetration rate on the continent, according to a 2019 paper by Deloitte. Namibia and Mauritius have insurance-penetration rates ranging between 6% and 7%, with the majority of less-developed markets hovering around 1% or below.

One of the strategies being explored by companies is microinsurance products, which are shaking up traditional financial markets. Microinsurance is mostly aimed at lower-income people, and is independent of the class of risk, according to another Deloitte paper titled Microinsurance in Africa.

To understand what exactly is meant by microinsurance, the authors say one should look at three perspectives in this market: the focus on the target group; the product; and the processes.

Micro refers to a specific target market, the low-income population in this instance. As for the product perspective, micro is defined by the characteristics of the products – smaller coverage and proportionally smaller benefits. With process, micro relates to the way of designing, introducing and administering the schemes, say the authors.

Microinsurance is often distributed in co-operation with rural banks, savings and credit co-operatives, and NGOs. Insured crops and livestock can be used as collateral for loans to buy better equipment or otherwise improve the farmer’s yields, ultimately raising the standard of living, according to the Insurance Information Institute.

Microinsurance offers consumers financial protection against specific risks at small premiums, says Marius Botha, group CEO of microinsurer aYo Holdings. ‘The impact is transformative, as it shields people with lower incomes from the economic shocks that would otherwise keep them locked into an endless cycle of poverty,’ he says.

‘It is changing long-standing perceptions of insurance on the continent as complex and expensive.’ It’s a matter of time before micro- insurance starts competing in the same space as traditional insurance, ‘which has battled to deliver relevant, affordable products to lower-income and rural communities’, he adds.

Some countries in Africa offer more potential for microinsurers due to certain factors, including the adoption of technology related to microfinance or money-transfer products, and are more likely to be open to adopting similar technologies for purchasing insurance products. The prevalence of other service providers with high consumer reach, such as mobile-network operators also offers microinsurers the chance to form mutually beneficial partnerships.

‘Where microfinance products are already offered successfully in a market, credit-life products have been easily facilitated and, in many cases, have led to higher penetration of these products,’ according to Alex Kühnast, associate director and life insurance actuarial specialist at KPMG. He adds that lockdown measures have, in some economies, accele- rated the adoption of digital technologies by both insurance providers and consumers.

For Kühnast, the ability to reach people through mobile phones enables microinsurers to deliver products using free unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) capabilities.

Botha agrees. ‘There is no doubt that it’s the heavy lifting of mobile-network operators like MTN that is giving microinsurers the foundations and channels with which to reach not only mobile phone users but also their wider communities,’ he says.

‘Whether it’s the use of USSD or a zero-rated app – for those fortunate enough to afford a smartphone – zero-cost engagement channels make it a whole lot easier to deliver attractive insurance engagements. As the cost of smartphones decreases, we will be able to provide richer experiences to our customers.’

Microinsurers have seen relative success in Ghana, Zambia, and Uganda, and are also looking at the West African countries. These forays are mostly driven by the prevalence of mobile-network operators and the areas where they have a high customer and sub- scriber base, says Kühnast.

Countries such as Kenya, through the Insurance Regulatory Authority, are encouraging the public to buy microinsurance products. Some Kenyan insurance and non-insurance institutions have introduced micro-insurance products focused on primary risks such as livestock and crop, health, funeral and life insurance.

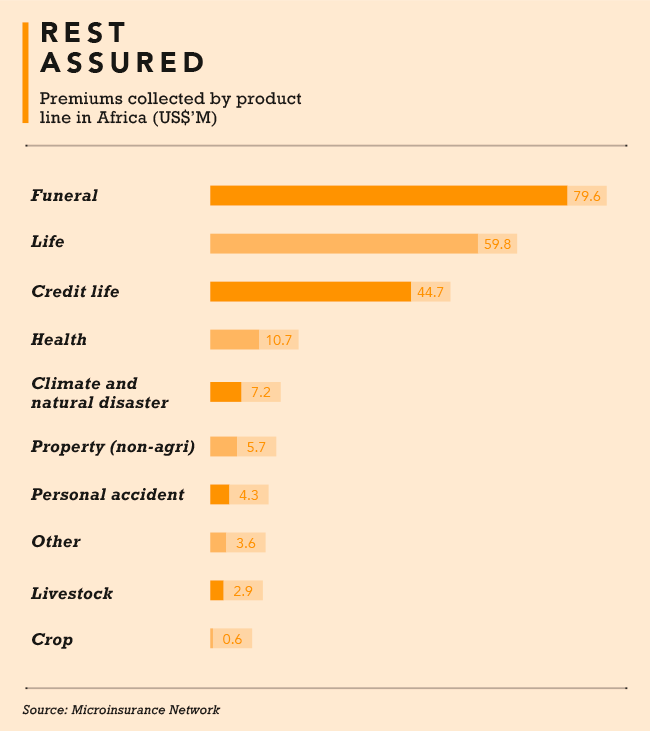

It’s interesting to note that the heavy uptake of funeral cover, a microinsurance product, in South Africa puts the country at the top for microinsurance penetration, but superficially so, according to Kühnast.

‘This high funeral-insurance penetration is not observed elsewhere on the continent, where both lower levels of access to funeral parlours and providers of funeral-insurance products, as well as different cultural beliefs and practices around burials and death, lead to lower uptake,’ he says.

Other institutions outside of insurance, such as banks, microfinance institutions, mobile money-transfer providers, and savings and credit co-operatives, have facilitated the deve- lopment of microinsurance through marketing and distribution, as well as serving as premium collection and claims payment points.

Kühnast says that Blue Marble Micro-insurance Group – backed by international brands including Aspen, Marsh McLennan, and other insurers such as Zurich, TransRe and ASSA – have been offering affordable insurance protection to farmers against extreme weather conditions in Zimbabwe and Mozambique, as well as East Africa for some time.

Countries with less restrictive, and more agile financial and insurance regulatory environments allow for faster and less costly innovation and thus have attracted more microinsurance providers, notes Kühnast. ‘Governments that provide incentives to both providers and consumers, to achieve a lesser burden on the state, can also facilitate more competitive and faster-growing microinsurance industries,’ he says.

Other notable players in the market include MicroEnsure, which uses mobile technology and data-driven approaches, in partnership with mobile-network operators and other providers, to provide microinsurance products. One example is its partnership with One Acre Fund, in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, to offer health and life insurance to smallholder farmers.

‘Many Africans see insurance as something that’s reserved for the middle class, or not to be trusted,’ says Botha, but microinsurance customers are seeing that it works, and they’re spreading the word.

AirtelTigo, in Ghana, for example, provided clients with access to life cover along with education on the product, with terms and conditions attached to it, of course. That, combined with claims being paid out in the community, led to increased awareness and uptake in cover.

There’s a definite need for microinsurance across these African markets, and companies have never shied away from opportunity and profit. In this instance, it may just be mutual to both supplier and client. ‘A lot of the industry’s growth is being driven by word of mouth. The more people see that micro- insurance is real, and the more they benefit, the more they talk about it in the community,’ says Botha. ‘This is helping break down a lot of the negative perceptions around insurance. Perhaps, once a critical mass of African consumers sees the value in micro- insurance, they will also see more value in “bigger value” insurance purchases in future.’

Insurance may be a tough sell to those locked in poverty, but these products can offer financial protection against devastating natural events, which are all too common on the continent.

By Sven Hugo

Images: Gallo/Reuters Images, Gallo/Getty Images