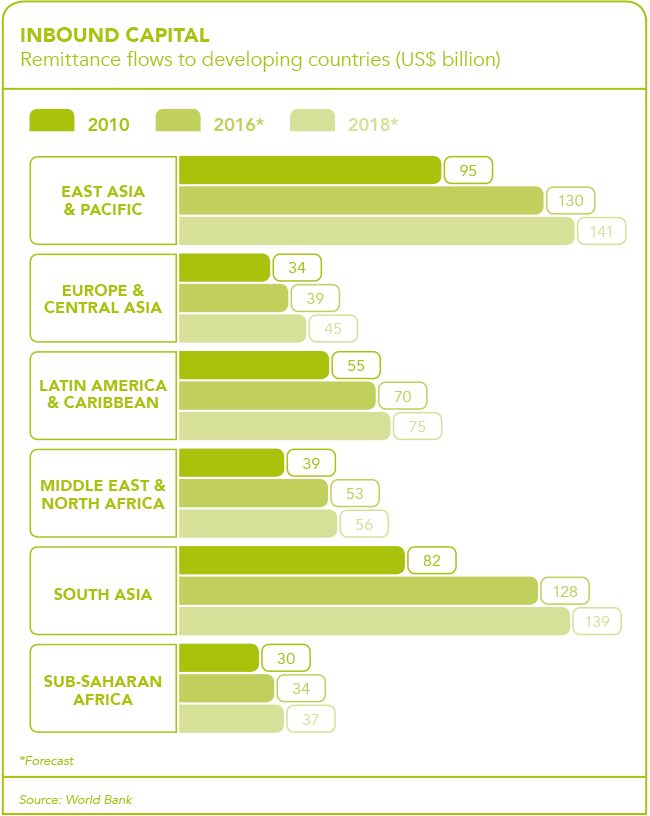

Gold, platinum, oil, agricultural produce… in dollar terms, one of the continent’s most lucrative – and overlooked – exports is Africans. Every year, sub-Saharan African migrants living in the diaspora send home more than US$30 billion in remittances. Those cash transfers help the folks back home pay for housing, healthcare and education, but they also have a positive knock-on effect on the broader economy.

Speaking to the BBC in 2013, Hong Kong-based academic Adams Bodomo said that the value of what those Africans living outside the continent actually send home to their families is more than what traditional Western aid donors bring into the continent through official development assistance (ODA). Bodomo claimed that in 2010 (the most recent year for which he said he could make meaningful comparisons), the African diaspora remitted US$51.8 billion to the continent (official figures put it closer to US$30 billion). According to World Bank figures, ODA to Africa that year was US$43 billion.

Bodomo claimed that the real figure for those remittances was and is, in fact, far more than that. ‘In the case of Africa, about 75% of remittances are sent informally,’ he said. ‘We can’t track that. For example, cash is sent through a friend who is visiting on holiday. If we add all that in, the diaspora remittances would be bigger by a factor of three or four times.’ Suddenly that US$50 billion-odd becomes as much as US$200 billion – and pretty soon we’re talking really big money.

Bodomo added that ‘family aid’ is also more effective than ‘official aid’ as ‘it’s better informed. An African family member abroad knows what is needed, whether it’s for school fees, to build a structure or grow a business. Compare that to traditional foreign aid and all the cumbersome structures it is distributed through – only a small amount of traditional aid ends up with the people who need it’.

Bodomo’s point was that ‘ODA donors should learn from these diaspora guys by targeting support to those who need it most – families and small businesses’.

His broader point, however, is one that’s also worth exploring. In 2014, more than 25% of Liberia’s total GDP was generated through remittance payments. That number was the highest in Africa, but it proves a point: the African diaspora plays a massive role in propping up and growing the continental economy.

In fact, the AU Commission has limited its definition of African diaspora to include ‘peoples of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality, who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union’.

Because of their personal or familial nature, remittances – as the African Development Bank recently put it – are ‘mostly used to increase household consumption, and are not structured as development projects.

‘Still, an analysis of recent developments reveals that their impact improves living conditions for receiving families. In addition, migrants develop strong skills abroad that help them create new forms of engagement in their countries of origin’.

The positive impact of those remittances is growing every year. The World Bank and other development partners recently revealed that the total money transfers by African migrants to their region or country of origin increased by 3.4% to US$35.2 billion in 2015. That total (which includes intra-continental transfers) meant that over the past four years, transfers by African migrants to their homes reached US$134.4 billion. And – as Bodomo said – that’s just the legal, or ‘official’, amount.

In April, data released by Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) showed diaspora remittances rising 8.6% to US$1.54 billion from the previous year’s figure of US$1.41 billion. This made remittances Kenya’s top foreign-currency earner. These inflows helped Kenya experience less currency volatility than its East African neighbours, and – as CBK governor Patrick Njoroge told Geeska Afrika – helped the country improve its reserves.

‘Traditional exports have weakened, but remittances remain strong,’ he said. ‘We have seen an increase in foreign currency reserves to the current US$7.5 billion. The oil import bill has also dropped, which has supported our efforts in stabilising the currency.’

Meanwhile, across the border, Uganda reported receiving US$1.1 billion, contributing to East Africa’s regional total of more than US$3.5 billion. Those numbers are high, but there’s a growing acceptance that they could – and should – be even higher. Go back to Bodomo’s 2013 interview with the BBC, and you’ll find a telling quote: ‘About 12% of diaspora money sent home through formal financial channels is swallowed up by bank fees,’ he said. ‘Governments should find ways to reduce this so more funds get to people who need them.’

At current levels, it costs more to send money to Africa than anywhere else in the world. The average cost of sending US$200 to Africa in Q2 2015 was 9.74%. While that was down year on year from almost 12% in 2014, it was still higher than the rest of the world. The global average in Q2 2015 was 7.68%. If you wanted to send that US$200 home to South Asia, your fees would be just 5.7%. But then came Q3 and Q4 2015, and two key meetings.

About 75% of remittances are sent informally. For example, cash is sent through a friend who is visiting on holiday

First, in July last year, was the Financing for Development conference, where delegates agreed to reduce the transaction costs of remittances to below 3% by 2030. In November, the EU/African leaders summit in Valletta, Malta, repeated that agreement that came as part of a package of aid pledges and reforms, all of which are aimed at reducing the increasing flow of migrants from Africa to the EU. The 3% commitment is huge, going much further than Bill Gates’ call in 2011 for G20 economies to cut remittance charges to 5%.

The World Bank has already estimated that if the transaction fees for remittances were to be reduced to 5%, migrants could save up to US$16 billion annually – putting money back in the pockets of the senders and the receivers.

So where do those transaction fees go? It’s a question worth asking, and it’s one that the World Bank answered in a report released this past March. According to that report, the most expensive way to transfer money is between bank accounts (11.12%), with credit/debit card services not much cheaper at 9.05%.

Mobile services cost just 6.9% – and while that’s still double the desired rate of 3%, it’s almost half the rate of a bank transfer, which explains why mobile services are so popular in Africa. In May, MTN Mobile Money became the fastest-growing method of receiving money transfers in Ghana via UK-based international money transfer firm WorldRemit, increasing by 13% per month on average. World-Remit processes about 400 000 transfers worldwide every month, with one-third of those received via Mobile Money.

In a statement, WorldRemit noted that the increased use of Mobile Money in remittances was also driving a new phenomenon called ‘micro remittances’, where people send smaller amounts more often.

‘Ghanaians are taking advantage of low-fee, instant mobile transfers to send money for specific purposes, right when it is needed. In the past, people often sent a single lump sum once a month. Today, with MTN Mobile Money, they can help with unexpected bills or family expenses whenever they arise,’ according to WorldRemit senior mobile analyst Alix Murphy.

‘Instant messaging also has a role to play in driving these type of micro-remittances,’ she says. ‘Ghanaians are constantly talking to their family and friends abroad and many of those discussions are about their personal finances.’

As remittance fees drop – and transfers become cheaper and easier through mobile options – illegal or under-the-radar transfers will emerge from the shadows. And as Africa’s households enjoy more income from relatives living abroad, the continent’s communities will surely grow and flourish.

Bodomo’s BBC interview in 2013 may be three years old now but his point remains as true as ever, and it bears repeating: ‘An African family member abroad knows what is needed, whether it’s for school fees, to build a structure or to grow a business.’