In October 2019, a Kenyan property developer became the continent’s latest – and East Africa’s first – issuer of a green bond. Acorn Holdings intends to use the proceeds of the KES4.3 billion (just over US$40 million) bond to finance climate-resilient accommodation for about 5 000 university students.

The student housing will be built according to international green building certifications that targets a minimum 20% reduction in water and energy consumption as well as in embodied energy in building materials. Through the green bond, Acorn wants to minimise the operational cost and carbon footprint of the buildings, while taking a leadership role in the region’s fledgling green-building market.

The company’s CEO, Edward Kirathe, likened raising corporate bonds in Kenya to ‘walking through a hurricane’. He is quoted by Bloomberg as saying that ‘the market sentiment for corporate bonds has been very bearish so the fact that we have been able, in the first round, to raise 4.3 billion shillings has exceeded our expectations’.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, green bonds typically prove more desirable than conventional bonds, because of their added transparency and measurable, positive environmental impact. They are an innovative way of unlocking capital to climate-proof emerging countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, which are considered particularly vulnerable to climate change.

As a relatively new financial tool that has been around only since 2008, green bonds raise capital exclusively for projects that address climate change and green issues – promising a ‘win-win-win’ situation for issuers, investors and the planet.

‘Demand for green bonds generally outstrips supply, and investors acquiring green bonds often hold them to maturity,’ states the Nairobi Securities Exchange in its Kenya Green Bond Market Issuer’s Guide.

‘As a result, green bonds are generally “sticky” in the secondary market as investors are not inclined to sell their green bonds. Requirements for enhanced transparency and disclosure associated with a green bond issuance will appeal to investors. Green credentials also enhance issuer reputation overall and can be part of a wider sustainability strategy.’

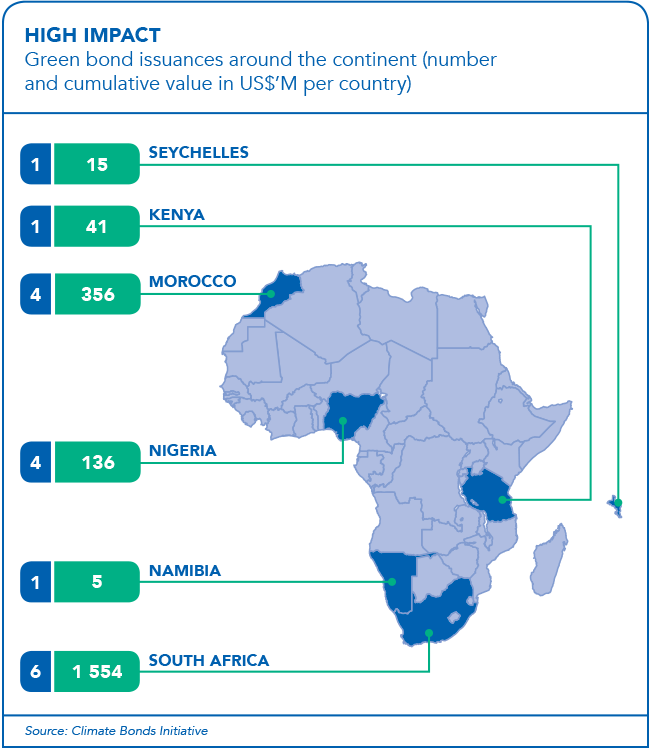

In Africa, 17 green bonds have been issued by six nations, led by South Africa, followed in chronological order by Morocco, Nigeria, Seychelles, Namibia and Kenya, according to the international Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). ‘A healthy one-third’ of these have gained Climate Bonds Certification, says the CBI, which runs the Climate Bonds Standard and Certification labelling scheme in support of the Paris Agreement.

‘Of the green bonds issued [in Africa] to date, energy has the largest use of proceeds allocation (US$988 million; 47%), followed by buildings (US$822 million; 42%) and water (US$116 million; 5%),’ CBI reported in October 2019.

By September, the cumulative global green bonds issuance was US$705.3 billion, with Europe as the trailblazer (accounting for US$277.1 billion of the total) and Africa playing catch-up (US$2.6 billion). The global target is US$1 trillion by the early 2020s.

In 2019, the global green bond and loans market reached a record US$231.2.6 billion, according to the CBI.

Africa’s first sovereign green bond, issued by Nigeria in December 2017, is among these certified issuances. The Nigerian government issued NGN10.7 billion to fund renewable-energy and afforestation projects. In another first, Nigeria’s Access Bank issued the continent’s first CBI-certified corporate green bond in April 2019. The five-year bond, which raised NGN15 billion, will be used to finance climate-smart projects in agriculture, transport and manufacturing.

There are many other firsts relating to green bonds, simply because the African market segment is so young. In March 2018, Growthpoint Properties became the first corporate to list a green bond on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s (JSE) dedicated Green Bond segment. The funds will be used to refinance top-rated green office buildings, and industrial and retail properties with 4-star Green Star ratings or higher from the Green Building Council of South Africa.

Further funding will go towards ‘greening’ Growthpoint’s buildings through measures such as renewable-energy installations.

In April 2019, Nedbank became the first South African bank to issue a green bond, aiming to raise funds for solar and wind renewable-energy projects.

A few months earlier, Bank Windhoek emerged as Southern Africa’s first commercial bank to issue a green bond (in December 2018). The Namibian lender was named 2019 Green Bond Pioneer in the category ‘New countries taking green bonds global’.

The CBI, which bestowed the award, said the recipients were at the forefront of the global climate finance challenge, and thanked them for being ‘pioneers’ who demonstrate to the world ‘that green finance is the tool to get us there’. According to Bank Windhoek’s sales and sustainability analyst Ruan Bestbier, their green bond ‘focuses on the man in the street. We aimed to create opportunities for eligible projects scattered all around Namibia; not just big-ticket items but also small residential renewable-energy installations. The major challenge was finding bankable projects, because a green bond is not a grant facility and the loans need to be repaid’.

The first wave of projects primarily consisted of solar PV installations. But depending on market conditions, Bestbier would like to diversify any future green bonds, possibly venturing into water treatment – a particularly pressing issue in the drought-stricken region. In addition to renewable energy and sustainable water management, the list of eligible projects includes energy efficiency, resource efficiency, green buildings, sustainable waste management, sustainable land use, clean transportation and climate change.

Bank Windhoek is due to release its first green bond impact report in early 2020, according to Bestbier, who adds that they hope to issue a second green bond in the near future.

Across the border in South Africa, the City of Cape Town (ZAR1 billion), Growthpoint (ZAR1.1 billion) and Nedbank (ZAR1.62 billion) are among the green bonds that were listed after the JSE launched its Green Bond segment in October 2017. As early as 2014, however, the City of Johannesburg pioneered its municipal, self-labelled green bond on the JSE to finance green projects such as solar geysers and biogas-to-energy. The auction for the ZAR1.46 billion bond, due to mature in 2024, was 150% oversubscribed.

Mpho Parks Tau, executive mayor at the time, said: ‘This marks a historic occasion, as [Johannesburg] is the first city in the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group to issue the green bond.’

The City of Cape Town (CoCT) followed with its own municipal, CBI-certified green bond during the devastating drought in mid-2017. Issuers and investors consider it an ‘overwhelming success’, according to the London Stock Exchange Group.

In its recommendations on developing the green bond market in Africa, the group states that ’the bond was transparent, outlining projects in electric buses, energy-efficient buildings, water management alternatives, sewerage-effluent treatment and the rehabilitation and protection of coastal structures, and the City referenced the significant marketing and reputational opportunity that existed for first movers in the market’.

The CoCT bond was more than four times oversubscribed and the book building took only two hours to raise ZAR4.9 billion in total bids.

The demand for green finance is not likely to slow down. Quite the opposite, according to Aunnie Patton Power, lecturer on innovative finance and impact investing at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business and founder of advisory firm Intelligent Impact.

‘Green bonds are part of the larger sustainable finance movement, which includes SDG [Sustainable Development Goals] bonds, and now also sustainability bonds, of which we haven’t had any issued yet in South Africa,’ she says. In her opinion, the ‘tide is turning’ in favour of sustainable investing, as inequality and climate change are set to affect every single person and every single company in the world. Big business has taken notice.

‘In 2020 we will be hosting the Global Steering Group Summit for Impact Investing in Johannesburg, which will involve about 1 200 people, including major international leaders representing trillions of dollars of capital,’ according to Patton Power.

These developments demonstrate the growing demand from a diverse investor base for locally issued green bonds. Africa needs to urgently capitalise on this, to adapt and mitigate looming droughts and other potential effects of climate change.