An investor wields power. By choosing where they put their money, they have the chance to influence the trajectory of the planet and people in a small way – while protecting the financial value of their assets. Just like South Africa’s big banks, which have stated they will no longer finance any new thermal coal-fired projects, investment or divestment choices could contribute to nudging companies into behaving in a way that aligns with investors’ values.

With the climate crisis in mind, still reeling from the impact of the pandemic and worrying about the rising cost of fuel and food – not to mention poverty, inequality and unemployment – Africa’s investors are becoming more serious than ever about sustainable investments. They’re following the global trend, which is seeing ESG (environment, social and governance) investments becoming progressively mainstream, now accounting for more than US$39 trillion in the five major global markets (US, Europe, Australasia, Canada and Japan), according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. This is a 34% increase over two years.

2020 marked ‘a pivotal year for ESG investing’, according to Moody’s, which noted a record 140% rise of inflows into ESG products for that year. And while the global market slump didn’t spare ESG funds, they have performed less badly than conventional funds. ‘The rapid growth in ESG funds coincided with a bull market that ended in 2022, making this lull a test for portfolio managers and investors alike,’ Bloomberg reported in June 2022. ‘ESG equity funds have done better this year, on average, than their non-ESG counterparts. All are negative, in line with the broad market sell-off, but ESG funds are down less than the others, despite typically tech-heavy, energy-light portfolios.’

Many high-yielding sectors that are common in traditional portfolios, such as fossil fuels and tobacco, are typically excluded from ESG portfolios. Instead, these tend to include early-stage businesses in renewable energy and tech, which will still take time to yield returns. This highlights once more that sustainability requires long-term, future-focused commitment.

Morningstar, a global investment research and financial services firm, explains that the rise in sustainable funds is partly owing to the launch of new funds, and partly to existing funds adding ESG factors to their prospectuses.

‘There has been a growing demand from investors to invest in funds, companies and causes that will act in the best interest of the environment, humankind and companies that do the same,’ says Victoria Reuvers, MD of Morningstar SA. ‘As much as the industry is doing its best to evolve to be able to offer credible products to satisfy end-investor demand, the industry is still in its infancy in South Africa. Most of all, we need to take a step back to define exactly what ESG means and looks like in a South African context. For example, should we be buying into funds targeting climate-positive investments only, or should we be targeting asset managers that think holistically about how they incorporate the ESG into their investment process?’

There is no simple answer to this. For one, the ESG rating methodologies are not yet standardised and scores can vary significantly between data providers. ‘One of the biggest confusions in South Africa is how ESG is defined in the retail space,’ says Reuvers. On top of this, there are different degrees of ESG, depending on the investor’s thematic priorities, choice of investment product, desired sustainability impact and expected financial return.

The ‘E’ of ESG typically covers themes such as climate risks, natural-resource scarcity, pollution and waste, and environmental opportunities. The ‘S’ includes labour issues including executive pay and the gender pay gap, as well as product liability, human rights, risks such as cybersecurity, and stakeholder opposition. The ‘G’ refers to ethics, corporate governance and behaviour – board quality, diversity and effectiveness, for instance.

Then there are the different shades or menus of ESG investing. For example, the EU classifies ESG funds as ‘light green’ or ‘dark green‘, depending on the strength of their commitment to sustainability. When it comes to investment products, the menu also ranges from low to high ESG focus – or differently put, from mildly flavoured (for products such as ESG exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, that prioritise financial return while screening investee companies’ ESG performance) to extra-spicy (for impact investing that prioritises societal and environmental outcomes over investment return).

ESG ETFs are a good gateway product for investors wanting to start their responsible investment journey. To provide some background… An ETF is a listed fund that tracks the performance of a basket of assets such as shares, bonds, property and commodities. It offers exposure to a wide variety of assets in local and global markets, all through a single investment. In 2020, ESG ETFs experienced dramatic growth in the US and Europe, and are slowly starting to enter the African investment landscape. South Africa’s first two ESG ETFs were listed on the JSE by Satrix in 2020, and in 2021 Sygnia listed a new ESG ETF that tracks the S&P Global 1200 ESG index. Such indices generally screen out companies involved in nuclear weapons, civilian firearms, tobacco and thermal coal, or are implicated in severe ESG-related misbehaviour.

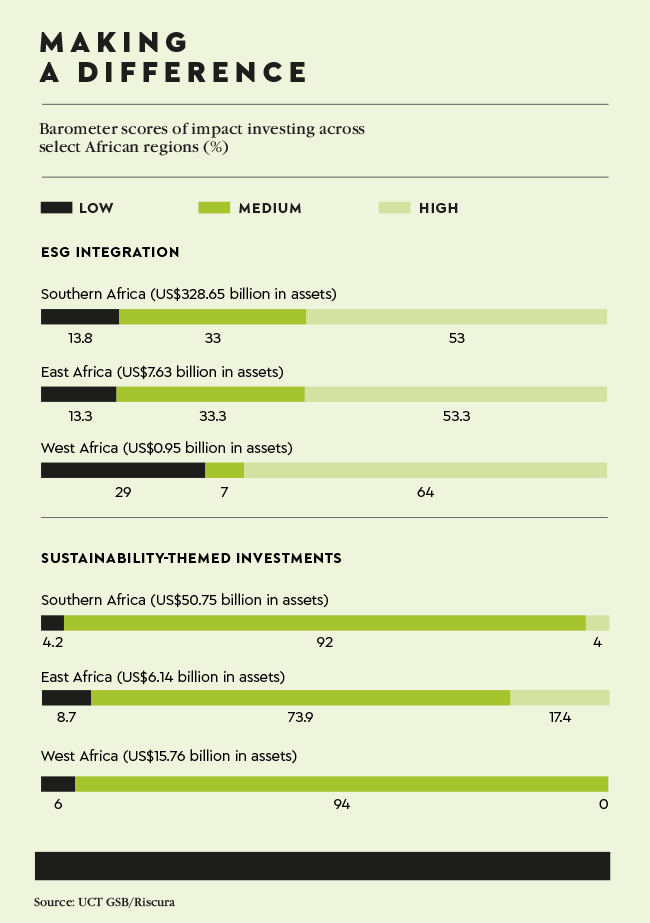

To improve the understanding of Africa’s ESG-investing landscape, the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB), together with investment firm RisCura, recently published the sixth African Investing for Impact Barometer. The research assesses 2 640 funds from 382 fund managers in sub-Saharan Africa based on their imple-mentation of the following five ‘investing for impact’ strategies, namely ESG integration (how ESG factors are integrated into investment analysis, valuation and decision-making); investor engagement (how active ownership influences company behaviour through proxy voting, board participation and/or engagement with companies on ESG matters); screening (how investments are included or excluded based on positive, negative, norms-based or best-in-sector ESG screening); sustainability-themed investment (how themes of environmental sustainability and sustainable development guide investment decisions); and impact investing (how investors intentionally aim at generating measurable positive environmental and/or social impact alongside a financial return).

In the sub-Saharan region, South Africa accounts for the highest amount of assets invested according to one or more investing for impact (IFI) strategies (an outsized US$600 billion), followed by Nigeria and Kenya. The barometer also found that the most widely used IFI strategy is ESG integration (US$336.1 billion in assets under management), with screening (US$231.3 billion) and investor engagement (US$145 billion) in second and third place respectively.

‘The growth of impact investing and sustainability-themed investment strategies is heavily dependent on decisions taken by market makers such as financial regulatory bodies and also political forces,’ according to Stephanie Giamporcaro, an associate professor at the GSB and in charge of the African Investing for Impact Barometer.

‘In Kenya, some interesting innovative products have recently been created. These are called diaspora funds and are accessible to the local and overseas retail market. In Southern Africa, there is growth, for example, in sustainable infrastructure funds that is linked to the renewed appetite for infrastructure investment.’

One of these is Summit Africa’s infrastructure fund, which focuses entirely on social infrastructure in healthcare, education and housing. The barometer says this bodes well for private-sector capital injections into other important themes such as water and sanitation. However, there is room to improve the supply of sustainability-themed investment products to attract more assets both for environmental and social issues, note the barometer authors. ‘The rising interest from stock exchanges in the three regions surveyed for consolidating the green bonds, but also progressively social and sustainability bond markets, could be supportive of this needed development for the continent.’

Another noteworthy collaborative innovation, by MSCI and Old Mutual Wealth, is the development of ESG scoring and classification of unit trusts offered to individuals. According to the barometer, ‘this potentially empowers retail investors with information to select unit trust portfolios that resonate with their desired IFI objectives’.

Most recently, COVID-19 inspired some impact investors to identify product-development opportunities. The authors highlight the agile response by Sanlam Investments, which seeded a series of impact funds aimed at supporting business to be resilient and recover from the pandemic disruptions while seeking financial returns.

Giamporcaro says there has been progress in IFI strategies since the barometer launched in 2013, in terms of hiring ESG professionals and disclosing more precisely how ESG is integrated into investment processes, and how investors engage on environmental and social issues, not only on the governance aspects. It will be exciting to see what’s next for Africa and how long it will be until ESG considerations become a standard measure for all investment decisions.