A few rays of light are breaking onto South Africa’s gloomy energy landscape. The coal-fired economy, with its rolling electricity blackouts – which are costing business up to ZAR900 million a day, according to the South African Reserve Bank – is experiencing a highly welcome ‘green’ boost. ‘Relentless load shedding from state-owned power utility Eskom is accelerating the clean-energy transition, as more businesses and homes urgently try to instal distributed generation solutions like rooftop solar PV with back-up batteries,’ says Chris Ahlfeldt, director of Blue Horizon Energy Consulting, and who also co-convenes a course on impact investing in Africa at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business.

South Africa is an outlier in Africa because it’s a high carbon emitter (the 13th largest in the world) and at the same time has positioned itself as the continent’s leader in the transition to renewable energy. The country has been hailed for the consultative way it planned its energy transition – from a coal-fired economy to net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Billed as the Just Energy Transition (JET), the ‘just’ refers to social justice, where the objective is to not leave behind any workers, communities and others severely affected by the phasing out of coal and other fossil fuels. To achieve net zero by 2050, South Africa will need about R6 trillion of infrastructure investments, according to the National Business Initiative (NBI).

‘There is a case for saying that the only way to release growth in this country is to break Eskom’s grip, and the way you do that is powering the massive roll-out of renewables,’ says renowned economic historian Adam Tooze, a Columbia University professor who recently gave a lecture series at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg that included the question, ‘who will pay for the climate crisis in a world of inequality?’.

He explains that at a macro level, a properly constructed JET has no trade-offs. ‘It’s a win-win,’ says Tooze, as quoted in Daily Maverick. ‘The trade-offs start at the micro level; they start with the coal mining regions, they start with the entrenched interests in coal, in the labour lobby that sees its interests tied up in heavy industrial manufacturing. They start with the auto sector and, even more acutely, gas-station attendants and that entire sector with people who have modest education. All those directly in the front line of the fossil fuel industry consist of less than a million jobs.’

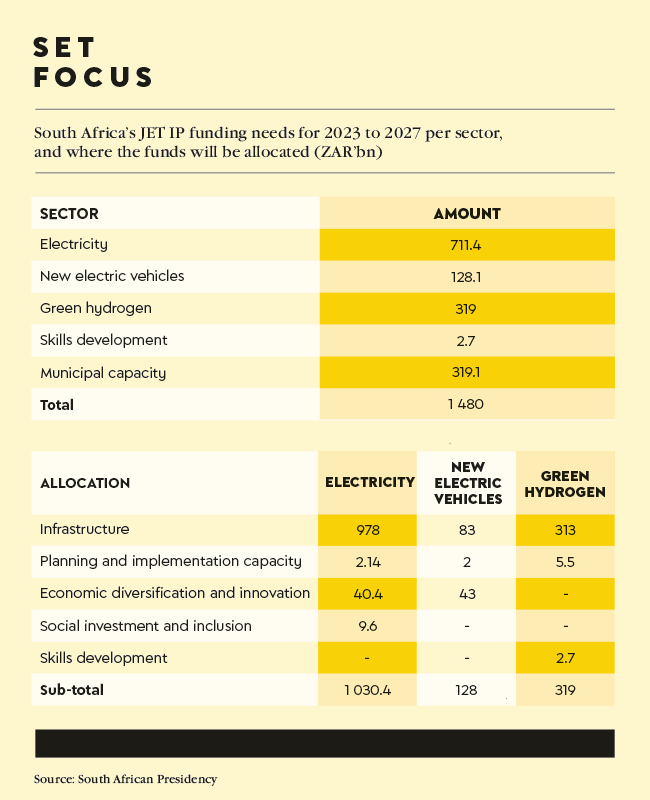

That’s why the JET goes beyond replacing the polluting, expensive coal-power plants with cleaner, less costly renewable energy. The focus is also on pathways towards new livelihoods for those who will lose their jobs when the fossil fuel-based industries wind down. South Africa’s JET Investment plan (JET-IP), which went public before the COP27 climate conference in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt, in November 2022, therefore also makes provisions for social investment and inclusion.

The ZAR1.5 trillion investment plan has three priority sectors (electricity infrastructure, green hydrogen and electric vehicles) and has allocated some of the funding to community impact; to enabling NGOs, civil society and academia; and to skills development. All the earmarked projects will have a strong localisation angle to further drive inclusive industrial growth.

South Africa was the first country to receive international funding through a JET partnership when the EU, Germany, France, the UK and the US pledged US$8.5 billion in the form of concessional loans, grants and investment and risk-sharing instruments at COP26 in Glasgow.

Indonesia and Vietnam have since followed this model by partnering with wealthy nations, while Senegal is one of the African countries interested in forming such a partnership in the quest for decarbonisation.

Tooze calls the renewable-energy revolution ‘a giant gift to Africa’ because of the continent’s abundance in sun and wind resources, in addition to having plenty of the ‘green’ minerals the world needs for the energy transition. He advises South Africa – and other African nations – to use their leverage not only on other governments but also on the corporations that are making the decisions on the decarbonisation effort.

‘What you need to do is to position yourself as a favoured partner,’ says Tooze, seeing as this will determine how African countries fit into the global green agenda. According to him, it’s a system in which there’s big money and profits to be made, as the US and China fight their strategic battle over the renewable energy transition.

In South Africa, government gave the green movement new momentum by lifting the licensing threshold for self-generated power and restarting its public renewable energy procurement programme in 2021. Since then, the private sector has been rolling out large renewable power projects, typically in partnership with independent power producers. Solar and wind energy are now cheaper locally than coal-based energy and also have shorter lead times to build.

‘Financial institutions play a critical role in mobilising capital not only towards those in the green sectors but also towards those in higher-emitting sectors in support of a clear transition strategy so as to facilitate transitioning the economy on a greener path,’ says Sasha Cook, Standard Bank head of sustainable finance, in an opinion piece in the Financial Mail.

‘We also see significant opportunities in the decentralised energy or off-grid space. Many prominent industrial players and mining houses are working with third parties to build their own renewable energy power plants to ensure a secure and consistent energy supply.’

The mining industry alone accounts for 7.5 GW (with a ZAR150 billion-plus price tag) of the 9 GW of energy projects in solar, wind, gas and battery storage that South Africa’s private sector has in the pipeline, according to the Minerals Council South Africa. It expects 3 GW of the 9 GW of private sector power generation to be completed by end-2024.

Over the past decade, 86% of Standard Bank’s new energy lending has been to renewables. ‘One recent transaction where we facilitated the financing of the project is with titanium producer Tronox,’ says Cook. ‘The company partnered with South African independent power producer Sola Group to construct a 200 MW solar-power plant to ensure a reliable energy supply, which will also see them reduce their carbon emissions by 13%.’

Meanwhile Ahlfeldt says that a just transition must not forget about renewables finance for small business and low- to middle-income households. These typically can’t afford to instal distributed generation and energy-efficiency solutions that would allow them to benefit from the cost savings associated with clean energy, and potentially mitigate against load shedding.

‘It would be great to see some of the US$8.5 billion concessional finance from the international JET funding in South Africa deployed at the residential and small-business level to finance distributed solutions,’ he says.

‘Unfortunately, financing for these solutions isn’t widely available, easy to access from banks, or at affordable rates for everyone, so opportunity still exists for more inclusive financing solutions that would allow everyone to benefit from clean energy solutions.’ Ahlfeldt cites Massmart as a rare example of a retailer offering loans to customers to go solar. ‘This is helpful, but there is still a need to make the terms of these loans more attractive and affordable to low-income customers in particular,’ he says.

‘Lower interest rates and longer repayment time lines that align with the energy savings from going solar over the 20-plus-year lifetime of the equipment are a start in addressing these financing gaps. Likewise, affordable financing for complementary energy efficiency and water-efficiency solutions that save communities cash on monthly bills is also needed.’

At the municipal level, GreenCape’s alternative service delivery unit has a proven track record in providing renewable energy to low-income communities in the Cape Town area. ‘This programme facilitates community-led energy services in informal settlements while creating local jobs and enabling investment in services from a solar PV micro-utility to deploy like solar home systems, back-up batteries, and efficient TVs and lighting,’ says Ahlfeldt.

‘A community fund is also created from a portion of monthly payments, which can be used to fund shared community resources like community WiFi, community crèche, food gardens, bursary schemes and emergency funds. Opportunity exists for municipalities to learn from this experience and for more community solar programmes to be deployed across the country.

In South Africa, businesses are key agents in implementing decarbonisation, says the NBI, which has been instrumental in advising government and developing just transition and climate pathways for the nation. The organisation warns that South Africa must make the JET work for reasons beyond the obvious environmental imperative for the planet.

Otherwise, outgoing CEO Joanne Yawitch said in early 2023, the country would ‘risk losing up to 50% of its export value as our trading partners, mindful of their own climate change pledges, align trade and commerce to reflect their net zero commitments’. She explained that in 2024, the EU will impose significant tariffs on goods imported from territories that have a high-carbon economy and have effectively banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2035.

All this confirms that to compete in a low-carbon future – and sustainably secure its energy needs – South Africa is on the right path with its just transition to net zero.