‘The rest of Africa should look to South Africa as an example of how renewable programmes can lower tariffs and costs throughout multiple stages,’ says Michael Meeser, chief investment officer at Revego Fund Managers. ‘As renewables become more of a focus for the continent, manufacturing needs to ramp up as countries will see the methodology to electrify their countries and bring power not only in cities, but rural areas.’

The South African Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP) programme was one of the leading initiatives in the world until it stalled around five years ago, seemingly under an agenda, during the tenure of former President Jacob Zuma. The REIPPP served as a global benchmark for how capital and services for renewable projects could be procured, according to many experts. Between its inception in 2011 and 2019 the REIPPP had attracted close to ZAR210 billion in private-sector investment, coming from South African entities such as Old Mutual, Red Cap, Phakwe and Pele Green Energy, among various others.

The Independent Power Producers office (the government agency for the procurement of renewable energy projects) announced a number of procurement rounds in 2021 following a longer than five-year hiatus, notes Vuyo Ntoi, co-managing director at African Infrastructure Investment Managers, Old Mutual Alternative Investments. ‘Things are moving in the right direction, and a significant amount of renewable power will be procured over the course of the next few years,’ he says. ‘The renewable-energy industry is also likely to consist of more embedded as well as commercial and industrial power players in the near future, growing the sector beyond power purchase agreements with government entities such as Eskom.’

Aside from South Africa, several financing agreements between the public and private sectors have resulted in numerous successful power utilities and ongoing projects across the continent. In December 2020, for example, the AfDB announced US$90 million in new donor commitments for the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa (SEFA). At the virtual launch, the bank also explained SEFA’s transformation into a so-called ‘special fund’.

Established in 2011 by the AfDB in partnership with the Danish government, the SEFA provides finance for renewable energy in Africa. The US, UK, Italy, Norway, Spain, Sweden and Germany are among the donors to the fund. ‘The new SEFA Special Fund is expected to expand, be more flexible, as well as more responsive to Africa’s fast-changing energy market, with a sharper focus on green mini-grids and green baseload, and offering a wider array of catalytic finance instruments,’ states the AfDB.

The bank committed US$530 million to finance the construction of a 343 km, 400 kV central-south transmission line to connect the north and south transmission grids in Angola, and allow for the distribution of clean energy between the two regions. Northern Angola has a surplus of more than 1 000 MW of mostly renewable power, whereas the south relies on expensive diesel generators, supported by government subsidies, the bank states.

The finance package, approved in December 2019 by the AfDB, comprises US$480 million in financing from the bank, along with US$50 million from the Africa Growing Together Fund and a US$2 billion facility sponsored by the People’s Bank of China and administered by the AfDB.

‘The funding covers the first phase of the Energy Sector Efficiency and Expansion programme [ESEEP] in Angola, which will assist the government to connect the country’s transmission grids and tackle limited operational capacity within the Angolan power distribution utility ENDE,’ the bank states. ‘Around 80% of residential customers in Angola aren’t metered, resulting in financial losses and reliance on government subsidies. As part of the ESEEP, 860 000 pre-paid meters will be installed and 400 000 new customers will be connected to the grid and effectively metered.’

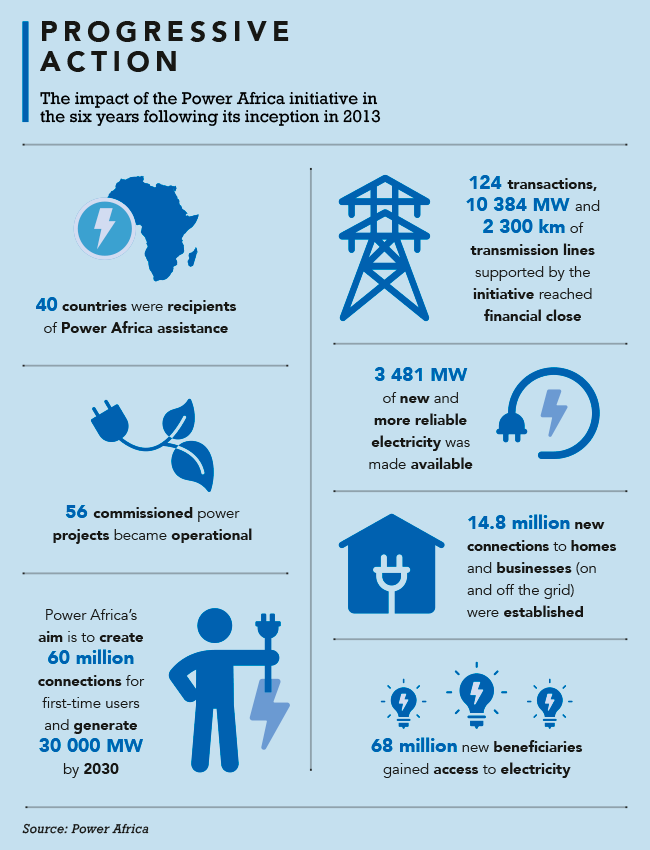

Other financing initiatives, including Power Africa, which was launched by former US President Barack Obama in 2013, have served as a channel for expertise and funding in Africa’s bid for energy. The initiative seeks to bring together technical and legal experts, the private sector and governments, to work in partnership in increasing access to power in sub-Saharan Africa.

According to Understanding Power Project Financing, handbooks published in partnership with the US Department of Commerce and the AfDB, power markets typically start off as fully funded, owned and controlled by government. This model places all kinds of constraints on government spending, which is why many governments have privatised revenue-generating power assets.

‘The government is able to benefit from financing structures encouraging private capital that help to free up its balance sheet for other priorities,’ the handbook notes. ‘As the market structure evolves, private participants gain comfort that there is greater transparency and a more efficient allocation of resources.’ The South African REIPPP, for example, was testament to transparency in the process.

Energy investment continues to favour countries and economies that have deep availability of capital from private institutions, liquid capital markets, and access to both domestic and foreign sources. Along with limited public finance, these are the key factors in a ‘supportive enabling environment’, notes the International Energy Agency (IEA).

According to data from the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), countries in Africa and the Middle East installed 894 MW of wind power in 2019 – and this is set to increase over the next five years. The GWEC estimates that a further 10.7 GW of wind energy will be installed in both regions by 2024.

In late 2019, West Africa’s first large-scale wind farm started generating power when the first turbines from the 158.7 MW Parc Eolien Taiba N’Diaye were connected to Senegal’s national grid. The developer, part-owned by global clean energy group Mainstream Renewable Power, spent 10 months building the wind farm. Parc Eolien Taiba N’Diaye will deliver 450 GWh annually to the Senegalese grid, increasing its capacity by 15%. The Senegal project is another win for wind power in Africa, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Large-scale development has so far mostly been confined to big North African markets, such as Morocco, and markets further down south.

In East Africa, the most significant development has been the Lake Turkana wind-power project in Kenya. The farm consists of 365 turbines with a capacity to dispense 310 MW of reliable energy to Kenya’s grid. Lake Turkana, for example, was funded by a consortium of global investors, including but not limited to the European Investment Bank, AfDB, Standard Bank of South Africa, Nedbank, Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO), Proparco (France), East African Development Bank and Triodos (Netherlands). The project’s debt-raising for the generation project was led by the AfDB, as the mandated lead arranger, with Nedbank and Standard Bank as co-arrangers.

The financing structure behind the Bujagali hydropower project in Uganda was a standout in Africa in 2008. It consisted of financing from several lenders, including US$360 million in loans and political risk guarantees from the World Bank Group. ‘By working with the private sector, civil society and the international donor community, and providing financing options that significantly reduce political risk, the World Bank Group hopes to catalyse private investment critical to lighting up Africa,’ then World Bank Africa region VP Obiageli Ezekwesili said at the time.

The project went through a noteworthy refinancing round in 2018, with a consortium of development finance institutions and commercial lenders putting more than US$400 million in loans into the project. Financiers included the IFC, a member of the World Bank Group, AfDB (joint mandated lead arrangers), FMO, Proparco, DEG (Germany) and the CDC (the UK), as well as South African commercial banks Absa and Nedbank.

The project is owned by Bujagali Energy, which has two main shareholders – Bujagali Holding Power Company and SN Power Invest Netherlands. They represent affiliates of Kenya’s Industrial Promotion Services and SN Power (Norway) respectively. The Ugandan government also holds shares in the company.

‘Energy generation and transmission are among the most pressing infrastructure needs in Africa, with important economic multiplier effects,’ according to Koffi Klousseh, Africa50’s project development director. ‘To successfully develop energy-sector projects requires collaboration among all stakeholders.’

As with many industries, the pandemic has temporarily put an end to the party. ‘This means lost jobs and economic opportunities today, as well as lost energy supply that we might well need tomorrow once the economy recovers,’ says Fatih Birol, executive director at the IEA. ‘The slowdown in spending on key clean-energy technologies also risks undermining the much-needed transition to more resilient and sustainable energy systems.’ However, as the recent investment into Angola’s energy infrastructure shows, the interest in renewable opportunities hasn’t so much dispersed with the pandemic, as it has simply been put on hold.