Green hydrogen may just be the fabled silver bullet in the fight against climate change. Made entirely from renewable energy, it could replace fossil fuels and feedstock (such as coal, oil, diesel, jet fuel and others that have been linked to global warming), and decarbonise multiple economic sectors.

South Africa has all the ingredients needed to produce and deliver this game-changer (chemical name: H) to the world – plenty of sun and wind to generate clean energy, and large reserves of platinum metals needed for the electrolysis process that creates green hydrogen (by splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, separating the H2O into H and O molecules). And it has the know-how and technology (notably Sasol’s proprietary Fischer-Tropsch gas-to-liquids process) as well as existing natural gas pipelines for transport, to develop an export-led green-hydrogen economy.

‘Moving in this direction presents a golden opportunity for South Africa to transition from being a key contributor to global warming to becoming a key contributor to global emissions reductions,’ says Rod Crompton, visiting professor at Wits Business School’s African Energy Leadership Centre. However, he advises moving quickly so as to not miss out. ‘Namibia and Australia have recently signed big contracts to supply green H2 to Europe. Someone is eating our lunch.’

His colleague David Walwyn, professor of technology management at the University of Pretoria, explains further. ‘At this point the stakes are high. Other solar-rich countries such as Australia, Namibia and Morocco have already approved major investments in green hydrogen. In simple terms, there is indeed a window of green opportunity. The recently published Hydrogen Roadmap provides a clear pathway in terms of how this opportunity could be realised. Compared to five years ago, there is certainly a great deal of activity on hydrogen in the country.’

South Africa’s Hydrogen Society Roadmap (HSRM), officially launched in February 2022, was developed by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and Hydrogen South Africa (HySA), with input from more than 100 other industry stakeholders as an action plan on how to get a successful, operative green-hydrogen sector off the ground.

The map leads to five ambitious goals, namely the decarbonisation of transport sectors (heavy-duty vehicles, shipping, aviation and rail); the decarbonisation of energy-intensive industry (steel, chemicals, mining, refineries and cement); the creation of an H2 export market (Germany/EU, South Korea, Japan and others); establishing a manufacturing sector for H2 products and excellence; and greening and enhancing the power sector and buildings (including better power-grid stability).

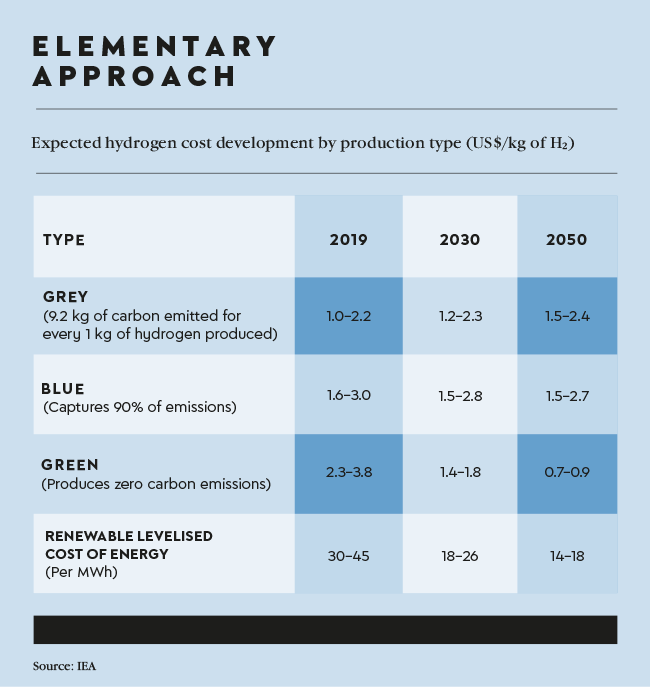

‘One of South Africa’s key advantages is that it already has an existing hydrogen market, albeit currently using only “grey” hydrogen,’ says Crompton. The colour of hydrogen refers to how it’s produced, as the gas itself is invisible. Grey hydrogen is generated from fossil fuels (gas or coal) in a process called steam methane reforming that emits harmful carbon. Blue hydrogen is made in the same way, but with lower emissions because the carbon is captured (and frequently utilised in industrial processes). Green hydrogen is the only type produced with zero emissions, using renewable energy and water electrolysis, and is therefore the most promising for decarbonisation. The transition from grey to blue to green hydrogen will be largely driven by market forces and also depend on the regulatory environment, according to the Hydrogen Roadmap.

South Africa currently produces 2 million tons (Mt) of the global hydrogen demand (all grey and mostly made from natural gas by Sasol). This volume is set to grow, as the country is projected to use 1.4 Mt of green hydrogen domestically for its own electricity generation and energy storage by 2050.

According to the DSI, the country has invested ZAR15 million to ZAR20 million a year in platinum-linked green-hydrogen development since 2009/10, which is hoped to pay off by creating 20 000 jobs annually by 2030, contributing at least US$5 billion to the GDP by 2050.

‘The Hydrogen Roadmap is an important statement of intent by the DSI,’ says Walwyn. ‘There are several drivers of the hydrogen economy, both local and international, and the roadmap is an honest attempt to realise some of the opportunities that could be presented by an emergent hydrogen economy.

‘Of the various catalytic projects, the most appealing in my opinion are the two that build on South Africa’s resources and expertise, namely the Platinum Valley and the project on Sustainable Aviation Fuels [SAF]. Platinum is essential for both fuel cells and hydrogen production via hydrolysis, and aviation presents one of the most challenging sectors to decarbonise – there is little chance that long-haul flights can be made using either batteries or hydrogen. Liquid fuels, and particularly green fuels, are the only realistic option in the medium term. South Africa’s prior experience with Fisher-Tropsch will be invaluable in solving the aviation problem.’

A Sasol consortium is working on the SAF project, exploring the feasibility of production at its Secunda Synfuels plant in Mpumalanga. The consortium aims to bid under the German government’s H2Global initiative; a trading platform that could assist South Africa grow into a hub for affordable, green fuel for commercial airlines.

Meanwhile, the Platinum or Hydrogen Valley, the other catalytic project highlighted by Walwyn, is an industrial corridor project along the N1 and N3 that revolves around three hubs with high potential for the green-hydrogen value chain, including SME integration and job creation – Johannesburg, Durban/ Richards Bay and Mogalakwena/Limpopo. Hydrogen demand in these hubs could reach up to 185 kt by 2030, or 40% (low scenario) to 80% (high scenario) of the demand outlined in the Hydrogen Roadmap. The initiative has sparked nine pilot projects in the industrial (ammonia, chemicals), buildings (fuel-cell power) and mobility (mining trucks, buses) sectors. Anglo American is nearly ready to launch the world’s biggest green-hydrogen-powered haulage truck – a 210-ton converted diesel truck currently being piloted at the company’s Mogalakwena platinum mine in collaboration with Engie and other partners.

Mining trucks can guzzle 134 litres of diesel every hour, so the green-hydrogen version is expected to save about 3 000 litres of diesel a day, preventing 8 tons of carbon emissions from polluting the air. Anglo American intends to replace its global fleet of 400 diesel trucks with hydrogen trucks from about 2024.

At the opposite side of the country, north of Port Nolloth in the Northern Cape, a feasibility study is exploring the potential of launching an export hub for green hydrogen and ammonia. Pending the outcome, Sasol has signed an agreement with the Northern Cape government to become the anchor developer of the planned Boegoebaai Green Hydrogen SEZ. Described as one of the first green hydrogen lighthouse initiatives to be developed in South Africa, the project has the potential to scale to a US$10 billion investment, bringing unprecedented economic growth and stimulating jobs in the province. At full capacity, according to the Northern Cape Economic Development Trade and Investment Promotion Agency, ‘the Boegoebaai plant could drive the development of 1 GW of dedicated renewable-energy capacity and 5 GW of electrolyser capacity producing 400 ktpa of hydrogen. The project is envisioned to utilise a 60/40 solar/wind supply [and] could create up to 6 000 permanent and 50 000 temporary jobs’.

The Boegoebaai project will comprise six components, namely an electrolyser park; desalination plant; green ammonia production plant; storage facility; solar/ wind and battery park; and supplier park for key common components. There is already international interest in the proposed deepwater port, which will be a greenfield development with liquid bulk and multipurpose container terminals, supported by a railway line.

Another flagship catalytic project, the CoalCO2-X programme, aims to use green hydrogen and pollutants (such as CO2, SOx, NOx) contained in the flue gas from coal-fired boilers to make value-added products – such as sulphuric acid and fertilisers – to support the country’s transition to low-carbon. The DSI has injected ZAR50 million into this initiative and, together with PPC Cement, is involved in demonstrating the flue gas conversion technology at a cement plant.

‘The biggest obstacle in the path of green hydrogen is the high cost of the electrolysis of water,’ says Crompton. Using coal to generate grey hydrogen is still cheaper than creating green hydrogen from renewables. By 2030 the average cost of green hydrogen along the Platinum Valley corridor will be around US$4/kg, representing a green premium of US$2 to US$2.5/kg above grey hydrogen, according to the South Africa Hydrogen Valley Feasibility Study report. Yet a report by the National Business Initiative, Business Unity South Africa and the Boston Consulting Group estimates that South Africa could push this price down to US$1.60/kg by 2030 due to its excellent renewable-energy resources – which would be highly competitive on the export market.

There are, however, still some legal grey areas when it comes to regulating green hydrogen. ‘Among the suggestions are that the Gas Act, which covers the basics of how a hydrogen economy should be regulated, would need to be updated to some extent,’ said Jason van der Poel, partner at Webber Wentzel, in a recent webinar. ‘We do have a developed National Environmental Management Framework, which requires environmental authorisations for certain activities involved in the green-hydrogen value chain, such as the storage of green hydrogen and green ammonia, water treatment, and so on.’ In his view, the Integrated Resource Plan, which regulates electricity procurement until 2030, also needs to be updated, as it currently does not make any provision for power generation for purposes of green hydrogen.

All these developments indicate that the country might be on the cusp of commercialising its green-hydrogen potential, but there is still a lot of work to be done. It cannot let this window of green opportunity close.