Across sub-Saharan Africa, from rural KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to the cocoa plantations in Divo, Côte d’Ivoire, millions of people light fires at night to stay warm and to cook their dinners. It’s impossible to know the exact figures but by some estimates, an over-whelming majority of the continent’s population relies on wood, crop and animal residues (biomass energy, in other words) to meet their household needs. And while it may seem outdated to urban folk who cook their supper using electricity or gas, that biomass power may very well be the future of Africa’s growing energy requirements.

South Africa’s Department of Science and Technology certainly thinks so. It recently established a research consortium with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), the Tshwane University of Technology, Wits University and a local bio-enterprise to explore new value chains for waste biomass. From their base at the new ZAR37.5 million Biorefinery Industry Development Facility at the CSIR’s Durban campus, they will investigate opportunities for the beneficiation of waste by-products from South Africa’s forestry, timber, pulp and paper industries, hoping to divert the waste from landfills and put it to innovative use.

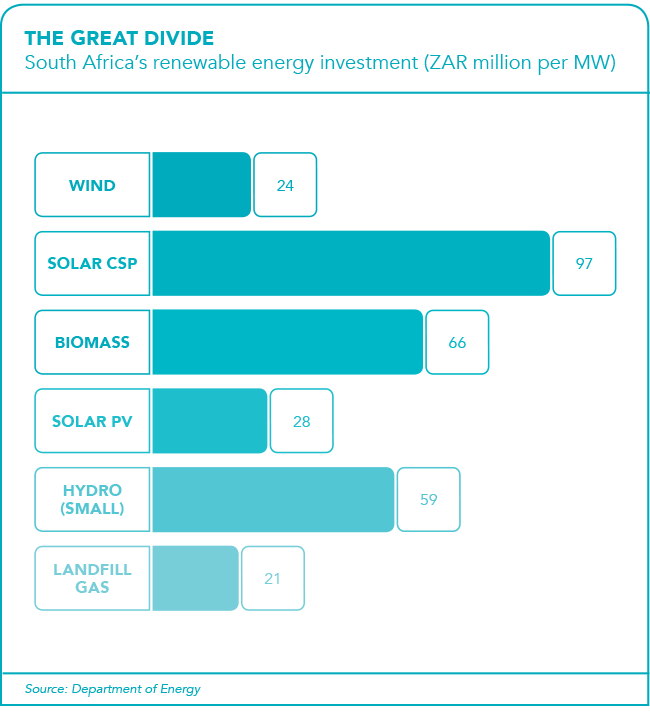

This is especially important in a country such as South Africa, where a significant portion of energy used is still provided by coal. Earlier this year, National Treasury announced that the country’s energy-efficiency savings tax incentive would be extended for three more years, and amended from ZAR0.45 to ZAR0.95 per kWh or kWh equivalent of energy saved. Tax breaks aside, African businesses are realising that the continent will not fully develop if hundreds of millions of its people (and enterprises) continue to live without reliable, sustainable electricity.

During a Res4Africa business-to-government high-level workshop in Ethiopia, the executive secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, Vera Songwe, said that energy was at the heart of development, and that access to electricity would lift productivity within and across sectors. ‘Right now the continent is moving towards the game-changing African Continental Free Trade Agreement [AfCFTA] where collectively we can wield the strength of the African continent better than we can individually, by trading more with each other,’ she said. ‘But the AfCFTA requires production, which requires energy.’

It should be fairly easy for parts of Africa to generate electrical power from locally sourced biomass. At least, that was the impression of Michael Kotter, CEO of Germany’s International Biogas and Bioenergy Centre of Competence. During a visit to Nigeria in mid-2017, he told a workshop in Abuja organised by the country’s National Biotechnology Development Agency that Nigeria has enough biomass capacity to provide its electricity. ‘I can see a lot of biomass being grown here, so my perception of Nigeria is that it is an ideal place to produce biogas and pursue the technology,’ he said. ‘I think Nigeria has very big potential. We in Germany have a growth period of half a year or six months. After that it is winter, and during this period nothing grows because it is very cold. But in Nigeria all year round you have plant growth and animal growing, and waste is produced and biomass is produced. So here you have actually better chances for this technology.’

By March 2019, UK organisation PyroGenesys was already working in rural Nigeria on a pilot project to produce low-cost, sustainable, off-grid electricity from agricultural waste residues. ‘The rural communities we aim to serve are not, typically, heavy users of electricity,’ says PyroGenesys CEO Simon Ighofose. ‘Their needs are relatively undeveloped, so it’s difficult for any electrification programme to justify the costs of extending the Nigerian national grid, especially in remote areas that are also poorly served by roads. [This] project will also focus on developing local smokeless cooking fuel production from waste agri-residues to replace wood-derived charcoal use, which is causing severe deforestation and human health issues.’

While that is a relatively small-scale project, in nearby Côte d’Ivoire plans are under way to produce biomass on a far larger scale. Côte d’Ivoire is a rare case in sub-Saharan Africa of a country that has a reliable power supply, with enough to export electricity to its neighbours. (It already exports to Ghana, Burkina Faso, Benin, Togo and Mali, and has plans to extend its grid to Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.) But with consumption demand continuing to rise, the Ivorian government is now trying to increase its installed capacity from just more than 2 200 MW to 4 000 MW within the next two years.

Cocoa pods play a significant role in that plan. As the world’s leading cocoa producer, Côte d’Ivoire has a vast supply of cocoa pods – thousands of tons of which are discarded and burned or left to rot after the beans are removed. In mid-2018, the US Trade and Development Agency gave grants for five power projects in the country, including smart-grids, a hydropower project and a 60 MW to 70 MW capacity biomass power generation plant. The plant – based in the cocoa region of Divo – will run on vegetable waste derived mainly from cocoa pods.

At the announcement of the grants, Ogou Yapi, MD of energy company Société des Energies Nouvelles said: ‘I want to move ahead quickly with the Divo cocoa biomass project, and this grant will help to do that. This is just the beginning. I see this as the first of many biomass projects here. This project will provide jobs, additional opportunities for cocoa farmers and the cocoa economy, and it contributes not only to energy security in Côte d’Ivoire, but it can also help us reach our goal of reducing our CO2 emissions by 28%, set at COP21 in Paris.’

There are examples like these across the continent – particularly among big businesses. In South Africa, listed consumer goods manufacturer Unilever recently unveiled a ZAR50 million biomass boiler – fuelled by wooden pallets and waste wood – at its Maydon Wharf factory in Durban. In Kenya, meanwhile, Tropical Power launched Africa’s first anaerobic digester, in the Naivasha region, drawing on 50 000 tons of vegetable and flower waste a year. But perhaps the most promising case study comes from Earth Centre in Johannesburg, where the University of South Africa, mining company Exxaro Resources and the South African National Energy Development Institute (SANEDI) recently unveiled an anaerobic biogas digester.

The 10 m3 machine uses – of all things – a feedstock of horse manure, diluted with grey water, to produce biogas fuel for heating, cooking and lighting applications. ‘It is the first time in the works of SANEDI and Unisa that this kind of substrate is used as a feedstock for biogas production,’ David Mahuma, GM of SANEDI’s Working for Energy programme, said at the launch. ‘This will open up a possibility for many stable owners to address the problem of “horse manure nuisance” that beset them.’

The technology behind the bio-digester is fairly simple. ‘It’s basically a bladder, with an inlet and outlet, and a gas outlet,’ according to Mahuma. ‘What you do is feed it on one side and gravity does the work of moving the stuff, and gas is produced on the other side. The only challenge is balancing the acidity in certain feedstocks such as food waste, but the beneficiaries are also trained to do tests on that because the mixture has to be as neutral as possible.’ SANEDI has already done similar work using feedstocks such as food waste, human waste, pig manure and cow dung. ‘Biogas is a proven renewable energy that changes the lives of poor communities living in rural areas,’ said Mahuma. ‘The installation of anaerobic digesters will be of great importance, not only in promoting the standard of living for people but by helping the environment by minimising the amount of organic waste. ‘Biogas usage is not limited to low-income communities, but also finds application in commercial and industrial applications.’

Still… Horse manure? It’s a strange new world when governments and businesses are looking at wood chips, agri-residues, cocoa pods and cow dung – and seeing them as a solution to the continent’s energy shortages. Yet it’s a world that inspires innovation, and one where waste products of any kind suddenly start looking less like a problem, and more like part of a desperately needed solution.