The COVID crisis has highlighted the urgency of global climate action and decarbonisation, increasing pressure on petrochemical firms to reinvent themselves. The pandemic-induced oil-price crash has further intensified the pressure on these companies to cut costs and increase efficiency, according to EY, which has released several workforce-related studies for this industry sector.

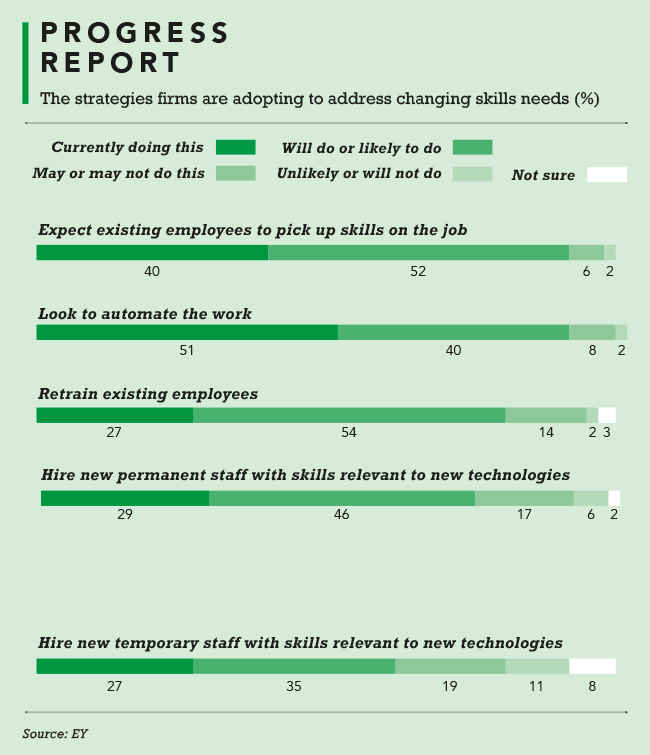

Its 2020 survey on digital transformation in the industry found that oil and gas companies need to invest in upskilling and reskilling their existing employees and, in addition, train a new generation of professionals, because ‘the present skill imbalance may be exacerbated by current market conditions as oil and gas budgets are slashed, workers are furloughed or laid off, and technology investments are viewed as optional’. Yet investments in both workforce and technology are far from optional; they are essential to surviving current market conditions, says EY. It cautions that oil and gas companies will face increasingly tight competition for talent – particularly as its research has shown that millennial and Gen Z professionals favour careers in tech and other industries over petrochemicals.

‘In my view, our country needs the oil and gas engineering skills, as innovative modified processes in the future can accommodate oil and gas as feedstock, and discharge low pollutants in the environment,’ says Diakanua Nkazi, associate professor at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering. ‘In support of the energy transition, the school has a bio-oil/oil and gas group, which generates innovative ideas to address the low carbon economy,’ he says, adding that the nature of these innovations can’t be revealed to the public at this stage.

Wits is the only tertiary institution in South Africa offering dedicated masters and postgrad diploma programmes in oil and gas engineering. ‘We are trying to strengthen the relationship with oil and gas companies for local internships of students and to promote the skills development programme,’ says Nkazi. In 2019 the university created the Oil and Gas Community under the SA Research Chairs Initiative, which launched a research chair for oil and gas engineering.

The department’s sophisticated lab features a distillation column and other specialised equipment, such as a lab-scale drilling fluid filtration unit and a GC-MS [gas chromatography-mass spectrometry] for gas and fluid characterisations. The university has an MoU with Total (the France-headquartered oil and gas major that changed its name to TotalEnergies in mid-2021, repositioning itself as a broad energy company). The multinational sends some of its experts as ‘Total associate professors’ to universities, such as Wits, to connect the petrochemical industry and academia, by lecturing in their technical fields of expertise.

Wits also offers short courses in oil and gas engineering as well as an introduction to offshore platforms and pipelines. ‘These short courses offer learning experiences for people wanting to enhance their skills to go further, as well as companies that want to give their employees the edge,’ says Nkazi, who adds that they also enable a conversion from other engineering and science-based degrees for specialities of petroleum engineering in order to produce engineers that are fully prepared to work effectively in challenging multidisciplinary environments of the energy industry and academia.

‘It’s important to recognise that a lot of skills are readily transferable between oil and gas, and broad engineering or technical disciplines,’ says Martin Solomon, an independent oil and gas expert currently contracted to PwC.

‘There’s a material overlap between these disciplines, so whether you are a mechanical engineer in oil and gas or a mechanical engineer in chemicals or a chemical engineer in any shape or form, the differences are not enormous. You can add on specific skills and train a mechanical or chemical engineer to become an oil and gas engineer.

‘Obviously there are some highly specialised skills that are unique to the oil and gas sector, which mostly relate to sub-surface skills – those required below ground level, such as geotechnical and geological skills,’ he says. ‘At some point in the future there will be a shift in the energy market and we will see oil and gas job losses kick in, but most of the technological capability of these professions can be transitioned into the new economy sectors.’

Another reason why petroleum engineers will be essential to the energy transition, according to Solomon, is the continued role that oil and gas will play in the energy mix for the foreseeable future.

Here the focus is on natural gas, which many consider to be the bridging fuel to renewables because it emits significantly less carbon than coal and oil. Others, however, warn that public funding of new gas projects will delay decarbonisation and may even lock the Global South into high-carbon pathways.

Adrian Strydom, executive director of the South African Oil and Gas Alliance (SAOGA), has been driving the local workforce readiness for a gas economy and regards recent discoveries as a ‘game-changer’ for Southern Africa. In addition to the massive liquefied natural gas reserves found in Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin, there has been the major offshore Brulpadda gas discovery near Mossel Bay, South Africa.

‘The initial uptake for employment will be slow, but as the region moves towards the development and production phases in the medium to long-term, we need to increase readiness,’ says Strydom. ‘South Africa’s upstream oil and gas industry is in its infancy, but thousands of our locally trained tradesmen, technicians, geoscientists and engineers are working across the globe. We need to determine more accurately what the gaps are between the current programmes and the competencies required to access future oil and gas industry employment opportunities. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel, as I do not expect the foundational, artisanal, technician and engineering skills to change dramatically.’

The South African Petroleum Industry Association (SAPIA) is working with the Chemical Industries Education and Training Authority to develop skills and update the talent pipeline for oil and gas and the broader chemicals industry. ‘The required skills will depend on what nature the oil and gas sector will become in the future. As an example, should exploration materialise, skills aligned to those activities would be required,’ says Avhapfani Tshifularo, SAPIA executive director. ‘The industry is currently running training for aspirant retailers; young individuals who have no experience in the oil and gas industry. The aim is to broaden the pool from which the members can draw potential retailers when opportunities become available,’ he says.

‘Furthermore, SAPIA has started to run masterclasses for members of the public. The aim is to expose people to the different business opportunities and support the industry’s transformation objectives.’

Meanwhile the business opportunities in another downstream sector – petroleum refining – seem to be dwindling. Tshifularo warns about the looming closure of South Africa’s refineries, which are in need of upgrades. Closing these refineries or converting them into import terminals would not only increase the country’s dependence on fuel imports, but also have a negative impact on skills.

‘Refineries employ highly skilled people to operate and maintain these facilities,’ he says. ‘Loss of refining capacity will mean the demand for these highly skilled jobs will fall, which will have ramifications up and down the skills development value chain – less requirement for lecturers to teach, less demand for new artisans and graduates to learn.’

While Africa’s commitments to a just energy transition will fundamentally reshape the continent’s petrochemical sector, PwC’s Solomon expects this only to happen towards 2050, with oil and gas likely to remain in the energy mix beyond this. His thinking is in line with the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), which said that even in the case of extreme decarbonisation and net zero emissions, the world would still require technologies that are very close to those of today.

‘Technologies associated with the energy transition such as carbon capture, utilisation, and storage and hydrogen power are nothing new to petroleum engineers,’ stated the SPE during its 2021 annual technical meeting in Dubai. Sub-surface skills and knowledge used to produce oil and gas will remain in demand, according to the society, with geothermal energy being just one example.

So the answer is yes, Africa is still set to benefit from oil and gas-related technical, artisanal and postgrad skills for the foreseeable future, and those who combine these skills with digital capabilities such as AI and data science will be especially sought after in the world’s quest for decarbonisation.