‘School-in–a-box’… ‘pay-as-you-learn’… ‘pop-up’ schools for refugees… When private-sector companies take on the troubled school system, they come up with unconventional models for Africa’s poorest. And their often innovative, low-cost approach is bringing good schooling to children who would otherwise not be able to access it.

Some of these schools charge less than US$100 a year, targeting families who have to survive on US$2 or less a day. The Centre for Economic Development (CED), a leading South African think tank, estimates that low-cost schools (defined as those with fees below ZAR12 000 a year) are educating a quarter of a million children in disadvantaged South African communities. Its study, Low-fee Private Schools: International Experience and South African Realities, further states that in 2010, 1 million such ‘budget’ private schools were operating in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda and other developing nations such as China and Pakistan. Between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of learners in low-income countries attending private primary schools doubled from 11% to 22% – and in some regions this number is even higher.

A study conducted by the University of Birmingham quotes a Nigerian census, which revealed that private schools in Lagos State catered for 57% of all school enrolments. Most of these schools were small, not ‘approved’ and run by a sole proprietor.

Jonathan Clark, director of the University of Cape Town’s schools development unit, explains why low-cost private schools are gaining momentum. ‘They provide choice,’ he says. ‘Given the poor quality of many state schools, the presence of “low-fee” schools offers people an alternative and, generally speaking, they appear to perform better than their state counterparts.

‘In South Africa, these schools will continue to expand but I don’t believe the driver per se is a move towards increasing privatisation of schooling. Rather it’s in response to the state’s inability to provide access to quality education. Remember, our in-school rates here are very, very high – up to 98.5% in the compulsory band of schooling.

‘To sum up our situation: we have equality of access without equality of opportunity. Elsewhere it’s about access to education in the first instance; so the growth potential for low-fee private schools on the rest of the continent is enormous.’

As far back as 16 years ago, the British Oxfam Education Report noted that the private sector was becoming an increasingly important provider of education across much of the developing world. It stressed, however, that ‘the notion that private schools are servicing the needs of a small minority of wealthy parents is misplaced’.

Take for instance Bridge International Academies, which started its first ‘school-in-a-box’ in the Mukuru slum of Nairobi, Kenya, in 2009, and now teaches around 120 000 children. Since its inception, Bridge has opened more than 410 nursery and primary schools in some of the poorest places in Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria, and is about to expand into India.

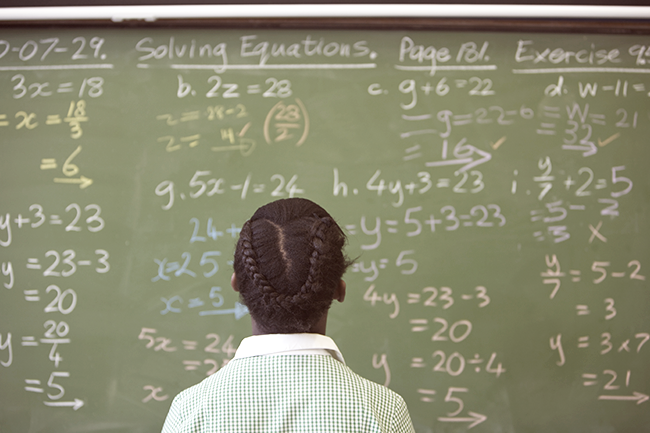

The for-profit model is data-driven, technology-enabled and rolled out on a massive scale. Bridge’s trademark bright green schools are simply built and their operations are standardised and hugely efficient.

There’s no paper admin as parents pay school fees via mobile phone, and the academy manager (corporate speak for ‘school principal’) is the only employee involved in school management, using a smartphone to synchronise admissions, school-fee payments and instructional monitoring with head office.

The teachers are mostly young women, recruited from the local community. They follow scripted lessons on their tablets, which are also used to record attendance and assessment scores, track lesson pacing and pupil comprehension.

‘There’s plenty of scope for larger school brands to consolidate smaller operators and to woo learners away from mediocre public schooling’

Bridge says it works with governments and civil society organisations to create, among others, ‘pop-up’ schools for refugees and other vulnerable populations. It envisages educating 10 million children across a dozen nations by 2025.

Microsoft’s Bill Gates and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg have invested in the chain, as have the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, the UK development finance institution CDC (formerly Commonwealth Development Corporation), Omidyar Network and Pearson, the largest education company globally. Pearson is involved in numerous other ‘edupreneurial’ ventures in Africa, including the low-cost Omega Schools for poor communities in Ghana. As stated on Omega’s website, its schools are often filled to capacity (500 students) ‘within 10 days of opening’.

Omega, whose tag line is ‘every child matters’, has introduced a cashless ‘pay-as-you-learn’ model. This sees families buying vouchers, sold in their communities, to pay for their children’s schooling on a day-by-day basis.

The school provider goes on to explain: ‘Apart from the fact that the daily fee fits well with poor parents’ daily cash flow, it’s the best way we ensure that we are accountable to our parents on a daily basis.’

The use of vouchers itself is nothing new, though in countries such as Chile, Sweden and the Netherlands, it’s the state that provides learners with vouchers to access secondary education. In contrast, Omega’s daily voucher addresses more basic needs: it buys a learner the tuition for primary school on any given day, as well as the required workbooks, assessments, school uniform and a hot lunch.

In South Africa, the low-cost private school sector is predominantly non-profit. The CED points out, however, that more for-profit institutions are opening for business, especially branded chains. And while they market themselves as ‘affordable’ and even ‘low-fee’ schools, according to the CED’s definition they are mid-fee rather than low-fee.

SPARK Schools is one example. Two South African MBA graduates came up with the idea for a network of primary schools dedicated to delivering accessible education with a high academic standard. After the success of SPARK Ferndale (launched in 2013), four new schools (Midrand, Centurion and Rynfield in Gauteng and Lynedoch in the Western Cape) opened in January 2016, taking the total to eight SPARK Schools. The current school fees are ZAR17 350 per year.

The innovative learning programme is ‘blended’, combining teacher-led instruction with computer-based instruction. This is modelled on an experimental Californian programme.

According to Michael Barber, chair of the Pearson Affordable Learning Fund (which backs SPARK): ‘The use of blended learning generates a lot of excitement in learners and the learning outcomes are demonstrably higher than the learning outcomes in the public system.

‘By combining whole group, small group and online learning opportunities, the cost of educating each student is kept low.

‘Expansion of the SPARK Schools model will ensure that, through innovation, their costs per student will be no more than the cost of educating a learner in a public school in Johannesburg.’

Meanwhile two independent school companies – Curro and ADvTECH – have been flying high on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

‘Private education does offer a rare economic sweet spot as parents are clearly prepared to make sacrifices to pay the tuition fees,’ writes columnist Marc Hasenfuss in the Financial Mail. ‘There is plenty of scope for larger school brands to consolidate smaller operators and to woo learners away from mediocre public schooling.’

Curro, which made an unsuccessful bid to take over ADvTECH in 2015, caters mainly for middle-income children aged from three months to matric. But its lower-fee Meridian brand is more affordable.

Meridian Cosmo City, for instance, charges annual fees of ZAR17 400 (Grade 00) to ZAR21 840 (Grade 12). In addition, the high schools require all learners to purchase an electronic device for e-learning. Curro aims to have 80 schools in its portfolio by 2020, totalling 80 000 learners.

Meanwhile ADvTECH, best known for its prestigious Crawford Colleges and Trinity-house private schools, has branched into the less expensive school segment. Last year it spent ZAR450 million on purchasing the Maravest group that includes, together with three premium and two mid-fee schools, the low-fee Doxa Deo School in Gauteng.

ADvTECH also has a 40% interest in Star Schools, which focuses on online teaching. The programme is a partnership with the Department of Education and public and private funders to boost learner performance with matric re-writes, Saturday schools and pre-exam sessions.

The success of these schools proves that there is a need in Africa for low-cost, high-quality private schools. However, critics argue that any kind of school fee is too much for the poorest of the poor and bemoan standardised teaching methods and untrained, low-paid teachers. But as long the over-burdened state education systems cannot cope, millions of learners – who would otherwise not receive an education – may benefit from chain schools and franchises.

For now, however, the innovative schemes of ‘school-in–a-box’ and ‘pay-as-you-learn’ appear to be serving their purpose of educating Africa’s youth.