The 2022 academic year is going to look like no other, both for university students and for faculty staff across the continent. Radically evolving education systems have seen an emergency shift to online learning, break-neck technical upskilling on all fronts and, latterly, an attempt to distil the chaos of the past two-plus years into lessons and applications that create a sustainable future. Throughout it all, traditional higher-education institutions have had to contend with perennial issues – a lack of funding and inclusivity – becoming even more urgent.

While thousands of column inches have extolled the virtues of online learning, describing the forced conversion of many traditionally in-person teaching institutions to virtual as ‘long overdue’, the idea that it represents a silver bullet to make education more accessible and affordable for students and universities across sub-Saharan Africa ignores the complexity of this shift.

‘The case is often made that online learning is more affordable. However, designing online learning and teaching activities, if done correctly and thoroughly, can be even more expensive than designing physical learning and teaching,’ says Deresh Ramjugernath, a professor and deputy vice-chancellor of learning and teaching at Stellenbosch University (SU). ‘Not only is IT infrastructure and technology installation required, support is also needed for lecturers to teach – and learners to learn – effectively online. Although greater efficiencies can certainly be achieved through the use of learning technologies, such as wider reach and economies of scale, it is not necessarily cheaper to deliver quality online-learning experiences to students.’

Nevertheless, traditional tertiary institutions will be facing increased competition from exclusively online education platforms. One such platform, Unicaf, recently announced its intention to expand higher-quality remote education to 20 African countries. ‘Distance education can eliminate current barriers to higher education in Africa, imposed by space and time, and can dramatically expand access to lifelong learning,’ says Unicaf founder and CEO Nicos Nicolaou. ‘Using flexible delivery models, students will no longer have to visit a physical location at specific times and days. A modern higher-education institution, such as Unicaf University, no longer has to be at any specific physical location but, through the use of technology, can exist anywhere, anytime for students who wish to access study materials and complete a particular academic programme fully online.’

While some existing tertiary institutions do offer 100% online qualifications – such as the University of Johannesburg, where bachelor’s degrees in human resources management and commerce in accountancy, as well as a selection of diplomas, can be completed online – the majority of ‘contact universities’ are opting for blended models. This is in part due to tech-affordability issues, but also the costs of reskilling staff. Educators may have rallied admirably in their adaptation to online learning throughout the pandemic, but this is not a sustainable approach, since emergency remote teaching bears little resemblance to qualified remote teaching, which is a skill that requires dedicated training on the use of technology and its successful applications in a pedagogical setting. Another consideration is that online learning simply isn’t appropriate for all fields – ones that require a high degree of practical application, for example, such as laboratory work – and lacks individual attention and feedback in the moment.

That said, many traditional universities are expanding their range of content to include purely online courses.

‘Online learning has become a critical component [in] the delivery of niche and specialist programmes to different student cohorts, especially adult learners who want to expand their knowledge and skills,’ says Tiana van der Merwe, deputy director of the Centre for Teaching and Learning at the University of the Free State (UFS). ‘Despite technology opening up the classroom doors, one of the most important lessons we have learnt is the focus on the human element, and people’s context and experiences in the learning process. This is forcing universities to relook and renew the curriculum and ensure engaging and interactive online learning experiences that are relevant to learners and their environments.

‘Various institutions have opted for a model where the majority of the curriculum is provided online, with a few contact sessions to allow for some of the interaction and collaborative learning experiences. Technology has thus become an enabler during this time, but poses a new challenge of relevance and value to learners. The UFS is embarking on a blended learning future that will be embedded in the new Blended Learning and Teaching Strategy that is in development and will be finalised by the end of 2022. Online programmes will be part of this strategy, especially in niche post-graduate and short learning programmes.’

Last year, the University of Cape Town (UCT) launched its Online High School in partnership with the Valenture Institute, catering to students from Grades 8 to 12. For ZAR2 095 per month, students can attend the country’s ‘most affordable’ private school from the comfort of their living rooms, or one of a series of blended learning model schools for pupils who need the safety of the physical space as well as access to reliable hardware and internet connections. In addition, UCT offers free online programmes though global open-course provider Coursera.

The University of Witwatersrand’s (Wits) exclusively online content is currently limited to its popular short courses, as well as post-graduate diplomas from the Wits Business School and School of Governance. For the rest, the university has adopted a blended approach, which ‘allows schools and faculties the flexibility to use the best pedagogies, tools, platforms and modes of delivery for the particular course that they are teaching,’ says Zeblon Vilakazi, professor and Wits vice-chancellor and principal. ‘With the support of professional learning design and ICT, teams can now choose the best way in which to engage with students. For example, it is better to do scientific experiments in person in a laboratory, but this could be complemented with an online lecture or webinar at which an international expert speaks on the subject.’

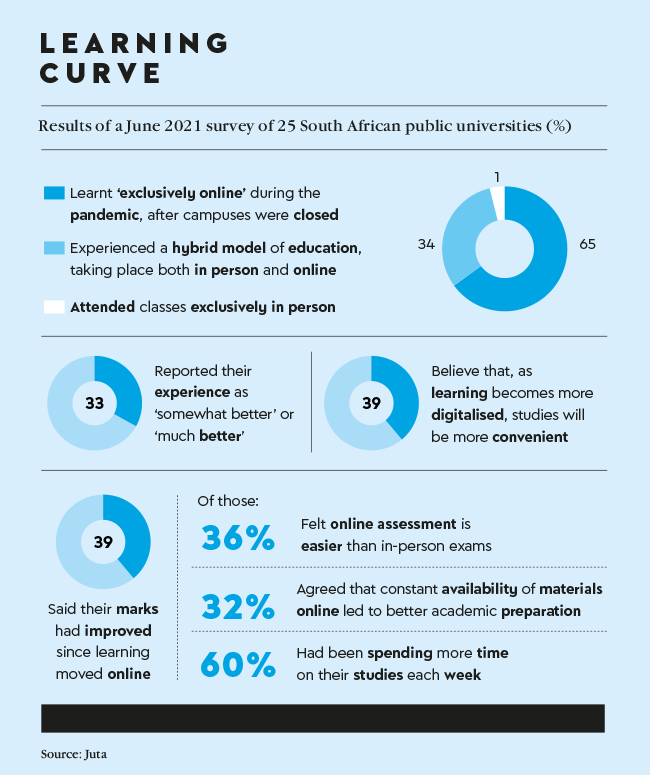

Apart from affordability of the technology and upskilling of staff, inclusivity remains one of the biggest challenges for online learning. Access to devices, data, electricity and suitable (not to mention, safe) spaces to study are major challenges for underprivileged students. A Department of Higher Education and Training survey of 48 981 students from 24 higher-education institutions in South Africa found that 96% of those who responded had learning devices in 2020, 89% of whom had smartphones. But half of all respondents found a smartphone difficult to use for learning.

Another survey of 13 119 students revealed that about 30% didn’t have a suitable study space, and 6% had no access to electricity. ‘The imbalance unfortunately stretches further than only access to technology,’ says Ramjugernath. ‘In South Africa the cost of data remains a huge stumbling block, augmented by not only the cost – and availability – of electricity, but also safely storing electronic equipment.’ Taking this into account, SU designed ‘data light’ learning material, such as short podcasts or voice-over PowerPoint presentations, rather than opting for data-intensive live-streaming lectures.

‘What is clear is that all students should have access to computers. At SU we have a mixture of students procuring their own laptops, a loan laptop scheme and computers that are supplied centrally within faculty contexts within computer-user areas.

‘Universities will need to grapple with the challenge of how to make sure that everyone does, in fact, have access to computers in the most cost-effective and efficient way.’

Wits invested significantly in three key areas to ensure that the digital divide was not exacerbated among its student community, particularly during the pandemic.

‘We took our academic programmes into the cloud and invested in a new learning-management system; we negotiated with mobile service providers to provide zero-rated learning sites for our students to access at no data cost,’ says Vilakazi. ‘We bought and couriered laptops to students who did not have or could not afford smart devices, and we allocated 40 GB of data to each student to enable them to access teaching and learning resources. In cases where students did not have access to electricity or networks, they were brought back to live in Wits residences so that they could access these amenities.’

With data and physical access to technology providing the foundation for online learning, advances in AI are set to provide the means to supplement a lack of access to essential facilities, such as laboratories.

The University of the Western Cape (UWC) joined up with Learning Science UK online pre-labs, which provides access to an interactive virtual lab, giving students essential foundational preparation before they enter the real-world laboratory, cutting down on the inevitable waste of reagents and breakages of equipment and glassware at the same time.

A combined total of almost 34 000 learning activities on the platform were accessed by UWC science students from 1 February to 31 May 2020, described by Learning Science MD Bill Heslop as the single-largest engagement across their interactive programmes by any university in the world in the first three months of a university-Learning Science partnership.

‘Immersive learning technologies such as augmented and virtual reality are some of the technologies that played a key role in learning during the pandemic and will potentially play a key role in years to come in helping students to visualise learning content without being physically present in lessons,’ says Mmaki Jantjies, education technology expert and adjunct associate professor at UWC. ‘Through 3D technology, immersive technology can simulate real classroom environments, allowing educators to simulate things such as chemical experiments to help students visualise learning remotely. As hardware – such as mobile phones and head-mounted gear – to support access to this technology becomes more affordable to everyone, it is proving to be one of the key enablers in supporting immersive remote and online learning.’

For now, a vision of the future for most African universities entails a hybrid-learning approach, where aspects of teaching most suited to the online medium – such as prep work and recorded lectures – can be completed before in-person classes, which are better suited to group or practical exercises.

However, until governments take steps to reduce the high cost of data, the potential for online learning to reach those who need it most is likely to remain stuck in the digital divide.