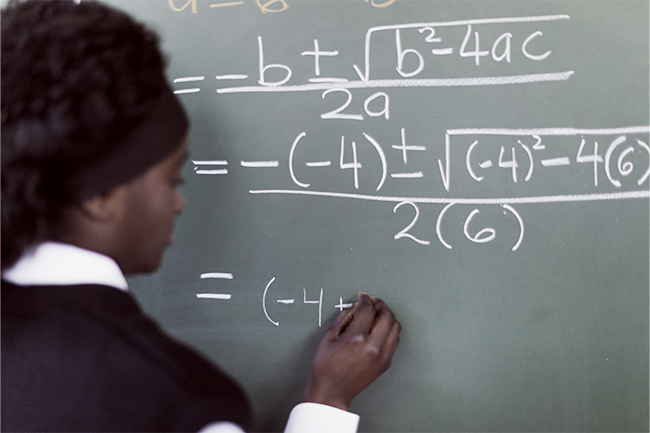

Pre-pandemic, 129 million girls were out of school globally, a figure that has likely risen sharply thanks to widespread school closures in 2020. What makes this figure even more galling, however, is that the social and economic benefits for broader society of educating girls is so well documented.

The most obvious is that educated women are more productive. They generate a higher income and put this income back into their communities and the economy. Every additional year of primary school increases a girl’s eventual wages by 10% to 20%. According to a study by the World Bank, failing to educate girls can cost countries trillions of dollars. More specifically, ‘limited educational opportunities for girls and barriers to completing 12 years of education cost countries between US$15 trillion and US$30 trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings’.

Educated women raise healthier children in every way. They are less likely to become a child bride or marry very young, they have fewer children, they are less vulnerable to domestic violence, and they are more likely to prioritise education for their children. All of this means greater independence, safety, access to resources and a significant contribution to the economy that extends beyond a single generation.

According to Unesco data, if all females in developing countries completed primary education, child mortality would drop by a sixth, saving nearly 1 million lives annually.

‘Educating a girl educates a nation,’ says Unesco director-general Irina Bokova, in a report released in October 2021. ‘It unleashes a ripple effect that changes the world unmistakably for the better. We have recently set ourselves a new ambitious agenda to achieve a sustainable future. Success in this endeavour is simply not possible without educated, empowered girls, young women and mothers.’ The good news is that, globally, girls’ enrolment in education has improved dramatically over the past 25 years, according to 2020 Unesco figures, with 180 million more girls enrolled in primary and secondary education.

In Africa, however, there is less room for optimism. Even though literacy levels have been steadily improving for the past five decades, a report by ONE, a global campaign to end extreme poverty, says that nine of the top 10 most difficult nations for girls to be educated are in sub-Saharan Africa. Seventy-three percent of girls in South Sudan do not attend primary school. In Burkina Faso, just 1% of girls complete secondary school. And in Niger, only 17% of young women (aged 15 to 24) are literate.

With the onset of the pandemic, millions more children are at risk – Unesco estimates 24 million learners, from pre-primary to university level, might not returning to school following the education disruption unleashed by COVID-19. Almost half of them are found in South and West Asia (5.9 million) and sub-Saharan Africa (5.3 million).

‘Education needs investment now more than ever,’ says Angeline Murimirwa, executive director at the Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED), a pan-African organisation making a significant impact. ‘Countries need to invest in safe school infrastructure, wash facilities and digital access, in teacher training and context-sensitive learning materials, and in the social support networks, as well as the financial support to keep the most vulnerable students safe and learning, and provide them with pathways to fulfilling livelihoods post-school.’

The problem is by no means limited to the alleviation of poverty and provision of education infrastructure, resources and skills (although these are, obviously, crucial) – there are multiple gender-specific barriers keeping girls away from school that must also be addressed. Sub-Saharan Africa has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in the world, and this has increased significantly since the onset of the pandemic. Disrupted economic activity means reduced household income – and when a choice has to be made whether to educate a son or a daughter, it is usually a son. In addition, child marriage is common. Some of the countries with the highest rates of child marriage include Niger (76%), the Central African Republic (68%), Chad (67%), Mali (54%) and Mozambique (53%). When girls are married, they are widely expected to stay home and take on the culturally expected roles of a wife – cleaning and bearing children. Not going to school.

Finally, monthly menstruation is an additional, gender-specific barrier for girls (aka ‘period poverty’), many of whom are compelled to stay home during their menses as they have no access to sanitary products, and subsequently may fall behind in their education.

Educating girls is a matter of justice, yes – and also an imperative for economic prosperity. Governments are mandated to address both, yet there is much the private sector can do to invest in this prosperity.

CAMFED – active in Ghana, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe – is arguably the most impactful independent organisation actively tackling the multiple factors that keep girls out of school. Since its inception in 1993, it has supported more than 4.8 million children to go to school, cultivated a network of some 178 000 alumni (via the CAMFED Association) who serve as mentors for young girls, and is active in 6 787 schools across 161 districts. The success of CAMFED lies in its pay-it-forward model, where every school graduate who joins the CAMFED Association shares her expertise and financially supports at least three more girls to go to school.

‘Private-sector backing is vital to support learning and ensure that educated girls can become independent women who play an equal part in decision-making and a country’s economy, and can rally their communities to support the most vulnerable children to thrive,’ says Murimirwa. ‘It can provide technical skills, jobs and opportunities for young women graduates.’

CAMFED has received valuable support from a number of private companies. ‘We developed the My Better World Curriculum [life skills imparted to vulnerable girl learners through associated role models] in partnership with education company Pearson, for example. And we’ve been partnering with teachers in Zambia and education company TES to develop context-appropriate methods for child-centred learning.’

It has also partnered with US multinational engine tech corporation Cummins in Ghana and Zambia to support girls’ transition from graduation to secure livelihoods. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, CAMFED receives support from Australian beauty retailer Mecca in assisting young women through school and into independence and leadership, training graduates as learner guides (life skills mentors to more vulnerable children).

Menstrual-hygiene brand Always, owned by Procter & Gamble, established the Always Keep Girls in School programme circa 2008, providing vulnerable girls with essential puberty education and donations of pads, and launched its latest intervention in October 2021. Since its inception, the programme has reached more than 200 000 girls and donated some 13 million sanitary pads in South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria.

By August 2020, Estée Lauder Companies Charitable Foundation (ELCCF) had released nearly US$9.5 million in grants since the onset of the pandemic, a portion of which went to the Global Fund for Children, which supports 10 grassroots organisations serving more than 17 000 children and youth in South Africa, Kenya, Mexico and the UK. ‘As well as reinforcing their communities’ response to the pandemic by providing trusted health advice, wellness support and PPE, the organisations are providing distance-learning resources in the form of a web series and delivering psychological support to young women and their families via an SMS system,’ according to the company.

Moleboheng Moshe-Bereng, senior marketing officer at the University of the Free State’s School of Financial Planning Law in South Africa, believes private-sector investment in girls’ financial literacy is also paramount. ‘It is of the utmost importance, as funding from the private sector can go a long way towards helping government and higher education institutions to have a wider and deeper reach, and help those who need it the most,’ she says.

‘In South Africa, specifically, there are quite a few corporates that have been offering financial literacy initiatives and outreach programmes, including Absa, Standard Bank, First National Bank, Nedbank, Old Mutual, Hollard, to name just a few.’

There are many more examples of private investment in girls’ education – and yet, still too few to offset the undermining effects of the pandemic, let alone realise the latest G7 goal of ‘at least 12 years of gender-transformative education for all’.

As the saying goes, it takes a village to raise a child. In the case of Africa’s girls, it takes a global village of key players, from activists to grassroots NGOs, to communities to governments, and – perhaps most essentially – to the private sector.