Since her graduation with a PhD in mathematics from Scotland’s University of Glasgow in 2019, she’s been known as Ghana’s Maths Queen. Now Angela Tabiri can add another title to her CV – the World’s Most Interesting Mathematician. She was bestowed the superlative at the ‘just-for-fun’ Big Internet Math-Off in July 2024.

As well as being the academic manager of the Girls in Mathematical Sciences programme at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Ghana, Tabiri founded and runs an NGO, Femafricmaths, which promotes female African mathematicians and mentors high school girls considering a career in the science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) fields.

A group of African educationists write in a recent World Bank blog that the continent already has a weak pipeline of students in STEM fields, with fewer than a quarter of higher education students pursuing STEM fields. Of those, less than 30% are women. ‘This issue is partially due to the lack of students’ awareness of the career opportunities in STEM,’ they write.

Quite clearly, Africa needs role models like Tabiri. And Alisha Raghoonanan. She is a project engineer and manager with Enel Green Power, and helps co-ordinate projects such as the recent construction of the Oyster Bay wind farm in the Eastern Cape province. She is also a mentor in her company’s Back to School programme to encourage school girls to consider a career in STEM.

‘My dream is to meet one of [my mentees] 10 years from now and for her to tell me, “I’m an engineer and I want to show you something I built”,’ she says.

And it’s not only a numbers game – or a case of Jill keeping up with Jack.

Wanjira Kamwere, business development manager at Microsoft’s MySkills4Afrika programme, says that it’s important to have diversity represented in STEM, and not just for the sake of numbers. ‘When women are pushed out of careers in STEM by systems of bias, this influences the products and services that STEM organisations create. Artificial intelligence or machine learning bias is a recognised concern for organisations developing products and services using this technology.’

According to Michele Ruiters, who runs the Leading Women programme at the University of Pretoria’s Gordon Institute of Business, companies also lose out at management levels by not appointing women. ‘By not sufficiently representing all voices and genders in top management, organisations are missing out on talent, contributions and skills that could add to the growth of businesses.’

Of course, the ones most disadvantaged are the women and girls themselves. According to the UN, adolescent girls and young women in low- and middle-income countries miss out on US$15 billion in economic opportunities owing to gaps in internet access and digital skills, relative to their male peers.

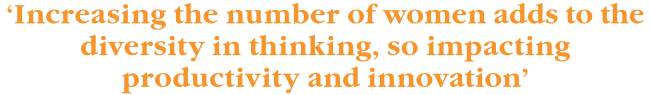

Ahead of International Women’s Day in March this year, which was themed DigitALL: Innovation and Technology for Gender Equality, the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) released new data on gender representation in STEM. While Africa has the highest proportion globally of women STEM graduates – 47% – those figures do not necessarily translate into careers in STEM. In Africa, 32% of R&D scientists are female; 20% of those employed in science and engineering are women; 29% of AI workers on the continent are women; and only 24% of women in Africa use the internet compared to 35% of men.

UNECA – which has trained more than 25 000 girls in AI, coding and gaming through its Connected Girls initiative since 2020 – ascribes the gender gap in STEM jobs to gender stereotyping; online and offline harassment; discriminatory practices; low digital connectivity and access; and the lack of role models.

One company that is not short of role models is Cape Town-based Lesedi Nuclear Services, which provides engineering, procurement and construction services to the mining, oil and gas and energy sectors.

In addition to holding the position of senior executive (outage services), Nicky van der Poel is MD of the Lesedi Skills Academy, whose goal it is to equip artisans – both women and men – with the required skills and knowledge to further their careers in the engineering field.

‘Nothing is impossible, I’m possible,’ says Van der Poel. Her advice to women leaders is – ‘as you ascend as a leader, uplift and empower the women within your organisation, fostering growth and development’.

Van der Poel and her colleague Phumeza Sidonti, Lesedi’s senior health and safety manager, are just two of a number of women occupying senior roles at the company.

Ursula Fear, senior talent programme manager at Salesforce, believes addressing the gender gap in STEM fields starts long before a woman enters the workforce. ‘We need to work together – as education institutes, as business, as caregivers – to help cultivate an interest in ICT among young girls by exposing them to all the possibilities ICT holds,’ she says.

As to that, South Africa’s National Institute for Theoretical and Computational Sciences is working in tandem with five universities – Cape Town (UCT), KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Witwatersrand (Wits), Johannesburg (UJ) and Stellenbosch (SU) – to offer guidance and mentorship to deserving Grade 12 female learners with a scientific bent.

The year-long STEM MentHER programme – conceived by Cerene Rathilal from UKZN and Lungile Sithole, director of UJ’s Soweto Science Centre – pairs up the learners with female academics and postgraduate students, who then become role models.

Speaking at the induction of the 2024 cohort of Grade 12 learners at UCT in March, professor and leading paediatric cardiologist Liesl Zühlke encouraged the participants to become agents for change. ‘We need to realise that women scientists have a vital role to play in scientific leadership and contributing to Africa’s development and transformation,’ she said.

‘How we build these ladders that get you where you need to go is going to make sure that we have better science for our community and better outcomes for women and [their] communities, and then create this cadre of women scientific leaders – and that will be better for everybody.’

Karin-Therese Howell, associate professor in the department of mathematics at SU, concurs, saying initiatives such as the STEM MentHER programme and African Women in Mathematics, as well as job shadowing and school visits, all aid in changing the landscape. ‘They send a message about diversity and inclusion. This is key to instilling confidence in aspirant women mathematicians. In any environment, increasing the number of women adds to the diversity in thinking, so impacting productivity and innovation.’

Salesforce’s Fear for one is looking forward to ‘the day that we no longer need to talk about girls or women in ICT as a specific focus area. In the meantime we need to keep nurturing potential, interrogating how to make ICT more appealing to girls and women, and actively debunk any remaining stigmas, myths and stereotypes around ICT being a male field’, she says.

One young women who is doing just that is Kiara Nirghin. The young South African is becoming something of a rock star in the global STEM arena.

At the tender age of 16, Nirghin won the grand prize at the Google Science Fair in 2016. Her project, Thirsty Crops No More, used orange peels and avocado skins to create an absorbent polymer that acts as a water retainer in soil.

The youngster from Meyersdal, Gauteng, was named as one of TIME Magazine’s most influential teenagers and one of the UN Young Champions of the Earth. Now the 24-year-old Stanford graduate is making the case for promoting women’s participation to the field of AI.

Writing in Fast Company, Nirghin argues that ‘the AI landscape is ripe for a paradigm shift, one where women are not just participants but pioneers’. Again it’s not a case of promoting women for the sake of reaching parity in numbers.

Nirghin cites a survey by Nesta, the UK innovation agency for social good, which shows ‘women are more likely than men to consider societal, ethical and political implications in their work on AI’.

According to Nirghin, the Nesta finding isn’t that surprising ‘considering women live in a world where they’re belittled on the basis of their gender, products in the market have been designed for men, and women with children are often expected to balance work with their role as primary caregivers. Ethical considerations – like gender equality – should be at the forefront of AI development, and we must prioritise transparency and accountability to develop AI systems that respect individual rights and promote fairness. As we stand at the cusp of this technological renaissance, it’s crucial that we harness the momentum of accelerationism to propel women to the forefront of AI innovation’.

While there’s a long way to go to improve women’s participation in STEM fields, with role models such as Nirghin, Tagiri and hundreds of other women in Africa who are following their passion despite overwhelming obstacles, there is always hope.