2020 has been a steep learning curve. Corporates have had to upskill themselves on how to manage mostly (or, in some cases, entirely) remote workforces. Healthcare services have had to rewrite their textbooks on how to cope with a global medical crisis. And across Africa and the world, families have had to figure out how to live in close quarters with each other during a series of tough lockdowns.

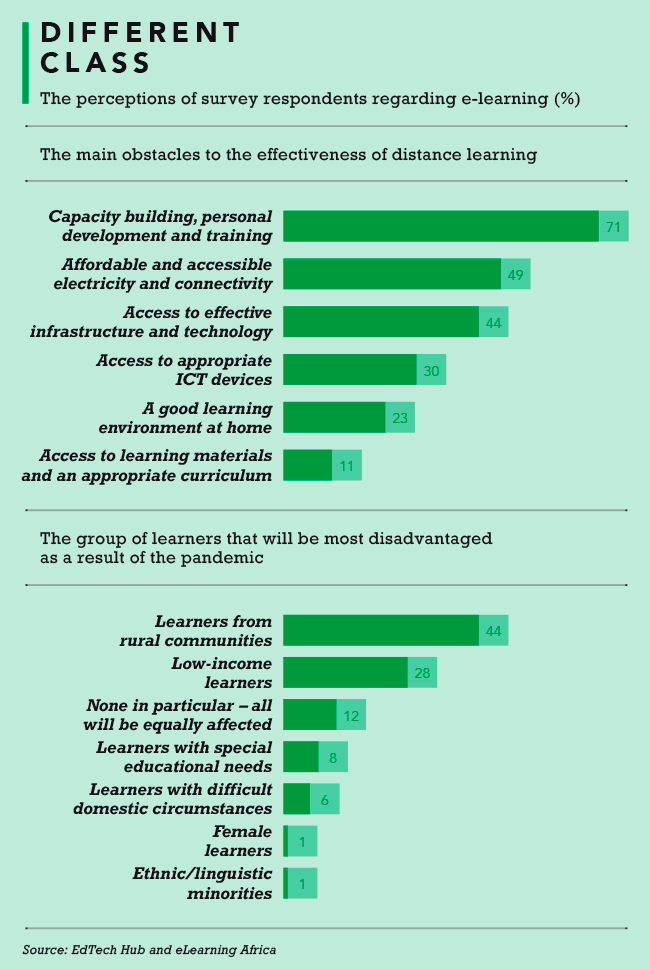

One group that has had to learn to adjust (arguably more than most) is the continent’s cohort of learners and educators. The COVID-19 crisis brought widespread school closures across Africa, with 97% of respondents to a major new EdTech Hub and eLearning Africa survey reporting closures in their countries, and 95% of those noting that all schools had been forced to close. (For what it’s worth, 92% saw the closures as being ‘essential’.) Suddenly, learners worldwide migrated to a distance-learning model.

For many this meant replacing their physical classrooms with Google Classroom. The free service used by teachers to send out assignments and communicate with their classes reported doubling its active users between March and April 2020, growing to more than 100 million. So while their parents were navigating the niceties of Zoom calls with clients and colleagues, schoolchildren from Cape Town to Casablanca were logging on to virtual classes and video sessions.

At least, some schoolchildren were, because while the theory of e-learning sounds wonderful, the hard realities of schooling in Africa are quite different; and the pandemic taught a tough lesson on the depth of inequality on the continent.

Mmaki Jantjies, associate professor in information systems at the University of the Western Cape, sums the situation up well in an opinion piece for the Conversation. ‘In theory, this [move to e-learning] could be an important step towards a fairer education system,’ she writes. ‘Digital platforms enable equitable access for learners to digital books, simulated science labs and related innovative learning resources. Electronic and mobile learning can thus be seen as an additional learning resource that can also help enhance access to learning tools. Access to e-learning is not a panacea to the challenges in South African education. But it does provide an opportunity to make access to learning resources for all children more equitable.’

However, as Jantjies highlights, the reality in South Africa, as in most developing countries, is very different. ‘Teachers have varying digital skills. Many families and teachers also cannot afford the data necessary to sustain some online learning activities,’ she says.

‘COVID-19 has shown that technology is no longer a luxury but an important component of the education process. In presenting solutions, a wide range of factors must be considered. These range from access to computers, to teacher training, to the social and economic challenges faced by teachers, pupils and schools in their communities.’

The EdTech Hub and eLearning Africa survey report, titled the Effect of COVID-19 on Education in Africa and its Implications for the Use of Technology, paints a more detailed picture. ‘Access to affordable electricity is a basic requirement for the development of any learning that is not classroom based,’ it states. ‘Too many parts of Africa, particularly rural areas, do not have this access.’

The report quotes Jossam (all respondents were referred to by first names only), a teacher from Rwanda, as saying that ‘the poor communities will be completely left behind. With lack of electricity and limited capacity to buy ICT equipment, this move will only increase the gap between the poor and the rich’. Tafadzwa, a school principal from Zimbabwe, adds that ‘there are remote areas where there is no electricity, the roads are inaccessible, and some teachers have never used a computer, let alone had access to the internet’.

Tabor, a teacher from Ethiopia, puts it simply. ‘We cannot afford to use technology to reach most of the students. There is no sufficient infrastructure.’

Yet despite those very real concerns about the impacts on the most disadvantaged sections of the population, there’s a growing sense that the current crisis could be a catalyst for long-term change in education – even in Africa’s least-developed countries.

As Alem, a teacher from Eritrea, explains, ‘catastrophic damage is already being done on education systems, along with other social and economic sectors, as countries have not been prepared for such an unforeseen pandemic of unprecedented magnitude. This damage is even more significant in the least-developed countries of Africa, including Eritrea, as they lack the necessary technological infrastructure to fill the subsequent educational vacuum created as a result of the pandemic. However, it is also a wake-up call for countries like Eritrea to turn the challenges into opportunities by investing more, in collaboration with development partners, in transforming and diversifying their education systems by complementing with contemporary alternative educational provisions of educational TV and contextualised online learning platforms’.

A South African e-learning entrepreneur named Godfrey points out that as smartphones become more affordable and penetration rates increase, mobile phones could solve the technological problems. ‘Self-paced learning requires the continual engagement that gamified mobile experiences can provide,’ he says. ‘TV is passive and expensive. Radio lacks essential visuals. Tablets, laptops and PCs are expensive and impractical.

‘Smartphone penetration is growing at a massive rate. In South Africa smartphones have a 91.2% penetration. In Tanzania, more people have access to a smartphone (53%) than to a TV (41%). Data costs are dropping dramatically and learning content can be zero-rated. Smartphones are the learning platform of the 2020s.’

Ruksana Osman, dean of the faculty of humanities at South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand, sees education as the pipeline for employment, where today’s learners – whether they’re in a Google Classroom in Cape Town, learning on a smartphone in Nairobi or struggling to find a physical classroom in Eritrea – are tomorrow’s employees.

Speaking specifically about the South African environment, she says that ‘corporate South Africa has just not woken up to the fact that the environment that the young people they are employing are coming from has changed dramatically. I hear it so often from people who are 45, 55, 65, claiming that “in our days we worked much harder…”, and “we put in much longer hours…”. The point is, you don’t have to work harder and put in longer hours today; you have to work differently in the environment in which young people are currently finding themselves’.

And that environment, she says, has changed dramatically – with or without COVID-19. ‘Ten years ago, if I saw my kid on the phone I would say: “Get off your phone and study!” Today my kid is studying on the phone. That transition has not been made by universities or by corporates. Sometimes you’ll have university academics saying that students only learn when they come to class. We know that there are different formats of learning. Going to class is a very important format, but it must be mixed with other ways in which students can learn, because not everyone can come to class every day, all of the time. Some of the best learning happens face-to-face, but there has to be a hybrid, or mixed, approach.’

Africa’s schools have stumbled into that hybrid learning model in 2020 – some by accident, some by design, some simply because classrooms were closed and they had no other option. Some 85% of respondents to the e-learning survey said they expected that the COVID-19 crisis will lead to more widespread use of technology in education in the future. At the same time, though, they expressed concern that this will also lead to significant challenges for marginalised communities, and may increase inequality.

All agree, however, that e-learning, in one form or another, is here to stay.

By Mark van Dijk

Images: Gallo/Getty Images