At independence in 1968, the tiny Indian Ocean island of Mauritius was one of the poorest countries in the world. It was wholly dependent on a single agricultural commodity, sugar, possessed no natural resources and was frequently buffeted by storms. Some of the world’s most prominent commentators considered its prospects to be dismal.

Nobel Prize-winning economist James Meade wrote, seven years before Mauritius achieved independence, that ‘it is going to be a great achievement if [Mauritius] can find productive employment for its population without a serious reduction in the existing standard of living. The outlook for peaceful development is weak’. Yet sceptics such as Meade could not have been more mistaken.

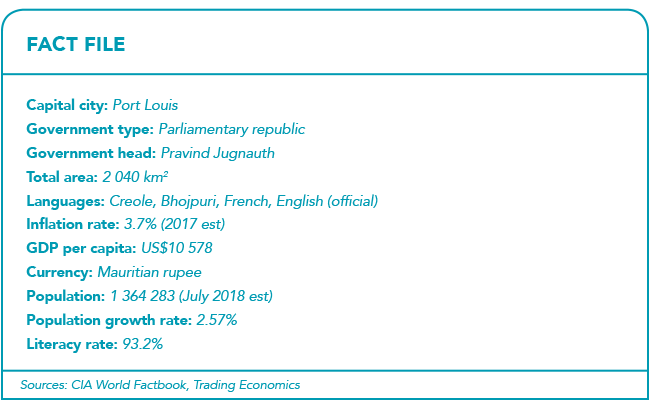

The island has achieved positive economic growth for the past 50-plus years. It is today an upper middle-income country with an average per capita income of at least US$10 000. Almost all Mauritians (87%) own their own homes and enjoy free education to university level, free healthcare, including heart surgery, and free transport to school. The island is a popular holiday destination with tourist arrivals numbering 1.4 million in 2018, about the same number as Mauritius’ population. Tourism accounts for nearly one-quarter of employment on the island.

Yet tourism and sugar are no longer all there is to Mauritius. The island has a thriving manufacturing sector, especially high-end textiles, and has become a financial centre with strong links to mainland Africa and Asia. Law firm Webber Wentzel describes it as ‘a preferred jurisdiction for fund managers looking to establish African-focused funds’. These days it is often referred to as ‘the Singapore of the Indian Ocean’.

There is, however, one significant difference to Singapore. In contrast with the South-East Asian powerhouse, Mauritius has been a multiparty democracy since independence. Most governments have been coalitions, a sign of the broad social consensus behind the island’s chosen openness to the global economy. But unlike many other countries that achieve a degree of stability through a crony capitalist division of the spoils of office, clean government is a feature of the Mauritian system. The then president had to resign in 2018 over mere allegations of financial impropriety.

This transformation was a product of deliberate policy. Mauritius has kept its economy open to the world and used its geographic position to develop as a trade hub and provider of services, sold both locally and, more importantly, offshore. Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth wrote in an article in the Financial Times last year that ‘we have grown because we have always been outward looking, with export-driven growth strategies and openings to foreign investors’.

These are not mere words. Mauritius is regarded by the World Bank’s Doing Business report as having the most business-friendly investment climate in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2019 it ranked 20th out of 190 countries in the Doing Business database, and was in the top 20 countries in the world in terms of three indicators (ease of paying taxes, obtaining construction permits and protecting minority investors). All taxes in Mauritius are pegged at a ‘harmonised rate’ of just 15% and there are no taxes on inheritance, dividends or capital gains. There are also no exchange controls, which means there is no additional cost when repatriating profits and dividends. Other international indices for the investment climate, democracy and governance also rate Mauritius the best in Africa.

Nico van Zyl, MD of Sovereign Trust (Mauritius), points out that it ‘has built a solid reputation as an international jurisdiction of substance’. He says that ‘with the support of its legislative framework and financial services infrastructure, the island offers an ideal platform for investments around the globe, with a focus on Africa and Asia’.

The government plans for Mauritius to become a high-income country by the mid-2020s. It will achieve this, says Jugnauth, ‘by further opening our country to foreign talents and investment, while encouraging innovation in all economic spheres’. The tertiary sector (tourism, finance, property, business outsourcing and services) is at the centre of this, accounting for nearly 70% of economic activity.

Van Zyl endorses Jugnauth’s vision. He says Mauritius is especially welcoming to investors attempting to escape the constraints of South Africa’s low-growth economy. ‘Many South Africans are looking at setting up headquarters or satellite offices in Mauritius, not just for its tax incentives and extensive tax treaty network, but also to gain access to the qualified yet affordable local workforce,’ he says. ‘Establishing a new business in Mauritius is extremely easy, with quick and efficient processes and no requirement for local partnership,’ says Van Zyl.

South African companies that have established a presence on the island include big names such as Investec, MTN, KPMG, Standard Bank and Aspen Pharmaceuticals. The development of a top-end global finance sector reflects Mauritius’ movement ‘up the value chain’. Investec describes Mauritius as ‘an international financial centre with attractive benefits for foreigners’. According to Gavin Butchart, financial director of Brenthurst Wealth, the financial services sector ‘originally centred on a few local banking institutions but has grown to now include 20 banks and many other service providers’.

Greater deployment of skills has happened across the economy. The sugar industry, for instance, once simply grew and crushed cane. But that has changed over the years. Established in 1926 as a dedicated sugar-cane processor and listed on the Stock Exchange of Mauritius in 2009, Omnicane could stand as a microcosm of the island’s development more generally. The new company resolved not to waste a single element of sugar production. Withdrawing to a single modernised ‘flexifactory’ complex at La Baraque, it sought diversification within what it calls the ‘cane complex’.

In 2019 Omnicane is not only still producing sugar (1.5 million tons of cane were crushed in 2018) but also 24 million litres of bioethanol per year. It is using the crushed cane remainders (called bagasse) to generate power, producing about 22% of the island’s electricity from this biomass source. But this is only one string in Omnicane’s bow. The company has leveraged its experience in the power industry, combined with Mauritius’ position as a base, to become involved in hydroelectric projects in East Africa. It also has a stake in a sugar cane complex in Kenya’s Kwale region and holds shares in Real Good Food.

Omnicane is also moving into property development. Its Mon Trésor project near the international airport is the island’s first certified ‘smart city’. The 480 ha complex combines residential precincts and leisure facilities with commercial and office areas, and – with the support of government – aims to consolidate the island’s hub role in international finance and business. It is intended to be the first in a series of work-live-play cities on the island.

Much of what the government does is aimed at supporting these sorts of movements up the value chain through infrastructure development. It is spending US$5 billion in the current five-year period on projects that include an ambitious transport construction programme to decongest the island’s roads. A 19-station light rail system, Metro Express, is under construction in the capital Port Louis and the first phase is scheduled to open in September. The harbour at Port Louis has been deepened and is now one of the deepest in the Indian Ocean and thus able to handle the largest container ships. Mauritius plans to develop as a trans-shipment hub where cargo between the continent and Asia is connected to feeder lines, particularly lines in Africa.

One of the booming sectors in Mauritius is property. Recent amendments to property legislation mean that foreigners can, for the first time, own commercial properties. According to Van Zyl, ‘South Africans are among the leading foreign purchasers of residential property in Mauritius, largely to take advantage of the various residency programmes that are available’. The legal amendments ‘have only added to the popularity of the country as an investment destination’.

The building blocks for Mauritius’ development into a high-income society are in place. Given the manner in which the small country has defied expert pessimism over the past 50 years, it would be foolish to bet against further success in this area.