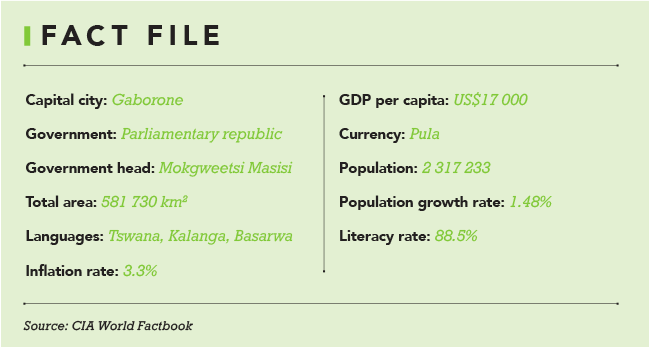

Botswana is frequently referenced as perhaps Africa’s greatest developmental success. It was one of the world’s poorest countries at independence in 1966, with most of its scant population engaged in subsistence cattle herding. At the time there were just 12 km of tarred road in the country. Today it is a middle-income country with a GDP per capita higher than that of neighbouring South Africa, a thriving wildlife tourism industry, and impressive public health and education services. More than 9 500 km of its public roads are now tarred.

Throughout its independence Botswana has had elected civilian governments that have emphasised national consensus (based on the consultative tradition of kgotla) as the basis of development. That consensus, revolving around developing the country’s massive diamond riches in partnership with global company De Beers, was painstakingly constructed by the country’s legendary first president, Seretse Khama. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which has ruled continuously since independence, claims consensus is its core philosophy.

Revenues from diamond wealth have been used to finance education, infrastructure and public health. However, Botswana remains a developing country with a small population (about 2.3 million) and a heavy dependence on a single commodity that is subject to global market fluctuations.

Current concerns are driven primarily by the faltering international diamond market in 2020. Diamonds account for 60% of Botswana’s total exports and about one-third of government revenue. But demand for diamonds slumped in 2019 and has declined even further in 2020 on the back of fears related to COVID-19, especially in China, the world’s second-biggest retail market for the sparkling stones behind the US. In 2019, diamond company De Beers – which has partnered with the Botswana government in developing the resource for more than 50 years – suffered its worst year since 2009, and its diamond sales from the second sales cycle in 2020 were valued at US$355 million, down from US$496 million a year ago.

The last time the diamond market turned significantly downwards was in 2015, with the main driver then being the resources meltdown and consequent tepid demand from China and the Middle East. This had an immediate impact on Botswana’s economy, with rough diamond exports hitting a five-year low and the country’s growth rate dropping from 4.9% to 2.6% . That same year, the government posted a rare budget deficit rather than the anticipated surplus.

Botswana’s fiscus has been well managed for decades. Its few deficits (2008/9, 2015/16) have been controlled by putting aside surpluses in good years. Public servants are well paid and have a tradition of being restrained in their demands for salary increments. The nation is ranked the second-least corrupt country in sub-Saharan Africa (after Seychelles) by Transparency International.

Concerns about the future, however, run deeper than momentary fluctuations in commodity markets. Botswana has an unemployment rate of 18.9%, affecting especially young people, one-third of whom are out of work. However, the deepest disquiet is about an aspect of development the government has long recognised – the need to diversify the economy and prepare for a future life beyond diamonds.

Economic diversification has been on Botswana’s economic policy agenda since the 1990s. While there has been some success, with developments in top-end wildlife tourism, other minerals (notably coal), financial services and along the beef-farming value chain, these have been somewhat marginal next to the weighty role of diamonds. What Botswana has not succeeded in doing is transitioning to export manufacturing. The AfDB, in its latest Botswana Economic Outlook, argues that this ‘requires fostering private firms that can integrate competitively into global value chains by addressing constraints that hinder private-sector engagement in trade and investment’.

There are in fact those who argue that Botswana has become more rather than less dependent on its diamond industry. It has developed along the diamond value chain, with De Beers shifting its sales events from Antwerp to Gaborone, the setting up of an independent diamond marketer (Okavango Diamond Company) and government support for a diamond hub in Gaborone dedicated to cutting, polishing and jewellery manufacturing. In the wake of these moves, Avi Krawitz of diamond-market commentator Rapaport noted in 2015 that ‘Botswana’s dependence on diamonds has arguably increased’.

The need to set a new direction may be straining the limits of Botswana’s democratic structures, which are dominated by a single-party dominant system, the BDP having been virtually unchallenged from independence to 2014. But in 2010 the ruling party split and the spin-off rival, now called the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), has proven a viable opposition. It won 17 of the 57 seats in Botswana’s parliament in the first general election it contested in 2014.

In the most recent 2019 elections, the BDP regained some lost ground, winning back two seats. But it took just 53% of the vote. One political heavyweight who supports the UDC is former president Ian Khama, son of the founding president, who stepped down in 2018 after a 10-year term as president. The opposition has contested the 2019 outcome, claiming extensive vote-rigging.

It can be difficult for outsiders to understand the political divide in Botswana, although personalities and clan loyalties are undoubtedly factors. It is not as simple as a split between urban and rural voters. While the opposition had previously dominated urban centres, observers were startled by the extent to which the BDP was able to win back the urban professional constituency in 2019. The most widely reported political issues in 2019 were the ruling BDP’s decisions to lift a ban on elephant hunting and to decriminalise homosexuality, but it is unclear what sort of traction these issues had among the electorate generally. There was considerable adverse international comment about the elephant-hunting decision, led by the usual outspoken Hollywood glitterati, but it is likely that it was popular domestically. Trophy hunting for elephants was banned under the presidency of Ian Khama in 2014, and the lifting of restrictions reportedly incensed the former president. Botswana is home to almost one-third of Africa’s elephants with numbers having risen from 80 000 in the 1990s to 130 000 today. The 27 000 elephants outside the country’s game reserves are frequently reported as coming into conflict with rural communities.

The immediate issue is the need to renegotiate the country’s 10-year diamond-sales agreement with De Beers, which will expire in January 2021. But although citizens of Botswana may want more from the country’s diamond wealth, there may not be much scope for expansion of their share. Botswana already has 50% of Debswana, its joint venture with De Beers, 15% ownership of De Beers itself and the right (via Okavango) to sell 15% of Debswana’s production. The current diamond-price slump will probably reduce options.

Botswana’s minister of mineral resources said in February that ‘what more really we need is to see jobs coming through; we want to see more young people participating in these jobs’.