Ten thousand marks and 260 guns – that was the price a German trader paid a local chief for a toehold of coastal Namibian territory in 1883.

Within a year and, in fact, at the behest of the trader Adolf Lüderitz, Germany’s Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had annexed the entire territory subsequently known as German South West Africa. Namibia had become another statistic in the so-called ‘scramble for Africa’ – the late 1800s campaign between Britain, France and Germany to divide up the continent.

Another indication of the arbitrary ‘barter’ nature of the colonial powers is seen in the long eastern finger of Namibian territory known as the Caprivi Strip. In 1890, this became part of German South West Africa, giving Berlin access to the Zambezi river and hence its colonies such as Tanganyika – now Tanzania – in East Africa. As part of the exchange, the British also ‘returned’ the island of Heligoland in the North Sea to Germany, and gained control of Zanzibar instead.

Although sparsely populated and semi-arid, the territory had the promises of mineral wealth (realised in a massive diamond rush that began in 1908). It served Berlin well as a bulwark, checking Britain’s imperial influence to the south and east, even though the British had taken control of the area’s only deep-water port, Walvis Bay, in 1797, later incorporating it into the Cape Colony.

German South West Africa was ruled with an iron rod (there were several uprisings by the indigenous people that were ruthlessly suppressed) until the First World War when South African troops invaded and – after a short campaign – conquered it. It was then mandated to South Africa by the League of Nations, the forerunner to the UN. It was the beginning of a long and fraught relationship – many would describe it as another colonisation – that Namibia would have with its more powerful southern neighbour until independence, brokered by the UN, in 1990, following over two decades of guerilla war and international pressure.

Even today, 25 years after independence, the two countries share a very close economic relationship, with the Namibian dollar pegged on a one-to-one parity with the South African currency and official government interest rates moving virtually in tandem. The rand is also freely accepted as legal tender in Namibia.

However, despite the geographical ties and the historical co-operation between the two liberation movements – the African National Congress and the South West African People’s Organisation, better known simply as Swapo – against the white minority South African government during the apartheid struggle, from a policy point of view Namibia and South Africa have moved in separate economic and political directions during the last two decades.

Although Swapo has won every general election with massive majorities, it has ‘toned down the liberation rhetoric’ as some observers have put it, and mostly embraced a neo-liberal and business-friendly economic framework.

This has paid off well. The World Bank and the African Development Bank have singled out the country for its progress. ‘Namibia has enjoyed considerable successes since it gained independence from South Africa in 1990, resulting from sound economic management, good governance, basic civic freedoms and respect for human rights,’ said the World Bank.

It summed up in a report: ‘Namibia has made significant progress in addressing many development challenges. Access to basic education, primary healthcare services and safe water is high and growing. Sound public policies are helping to lay the foundation for gender equality. Since independence, Namibia has been a leader in the area of natural resource conservation, with 43% of total land under conservation in 2012, up from 15% in 1990, and the country’s entire 1 570 km coastline enjoying protected status. Namibia maintains social safety net programmes for the elderly, disabled, orphans, vulnerable children and war veterans, as well as national programmes that provide maternity leave, sick leave and medical benefits to workers.’

With a per capita income of US$5.840 (in 2013) the country is placed in the World Bank’s ‘upper-middle income grouping’.

Other observers have also been complimentary. Writing in the Star newspaper at the end of 2014, Ashor Sarupen, the Gauteng spokesperson on finance for the DA, the opposition political party, praised the Namibian government’s pragmatism and ‘economic realism’.

‘Swapo, in government, has aggressively courted foreign investment, and provides legal guarantees against nationalisation,’ he wrote. ‘Exchange controls in Namibia do not prohibit the freedom of foreign firms to remit capital and profits. A free-trade zone in the form of the Walvis Bay export processing zone was set up in 1996 and has been extremely successful in attracting investment and promoting manufacturing. On the land question, despite some noises in 2000 after land grabs in Zimbabwe that placed pressure on Swapo, the government has taken a realist approach to land reform, looking to invest rather in affordable urban housing going forward [to the amount of N$45 billion over 18 years], rather than making noises about radical land redistribution.’

Sarupen described Swapo as ‘an outlier’, saying it was ‘a liberation movement steeped in the radical left that has transitioned into a governing political party tempered by economic realism. Its economic policies have been geared towards GDP growth and the voters have handsomely rewarded them with over 80% of the vote’.

While the South African economy has been stuttering, Namibia has racked up growth rates of around 4% a year and is expected to see expansion of nearly 5% in 2015. Yet apart from the impressive growth, the latter faces some steep challenges. Although it is classified as a middle-income country, it has extreme inequalities in standards of living and income distribution. According to the World Factbook, in 2011 its Gini coefficient was one of the highest in the world.

Unemployment remains high. In 2013, the rate was about 30%, and the country ranked 127 out of 187 nations surveyed in the UN’s 2014 Human Development report. As the World Bank points out, the country is on track to meet the Millennium Development Goals on education, environment and gender, but health goals are being hampered by the HIV/Aids epidemic.

According to an African Economic Outlook report: ‘Key risks to medium-term growth include weak global demand for mineral exports that would result in lower export earnings, adverse weather-related shocks that would further weaken growth in agriculture, delays in construction projects, and lower SACU [Southern African Customs Union] revenues due to the economic slowdown in South Africa.’

Namibia’s economy revolves heavily around mining, tourism, farming and fishing. Around 12% of GDP comes from mineral extraction industries, including diamonds, copper, lead, zinc and uranium. The mining sector employs only about 3% of the population while approximately 70% rely on agriculture as an income.

The backbone of mining has been diamonds: Namibia has provided massive amounts of the gems since the first stone was picked up near Lüderitz in the early 1900s. Between 1908 and 1914, for example, nearly 7 million carats were mined, and to date the industry – both land- and marine-based – has been responsible for around 90 million carats.

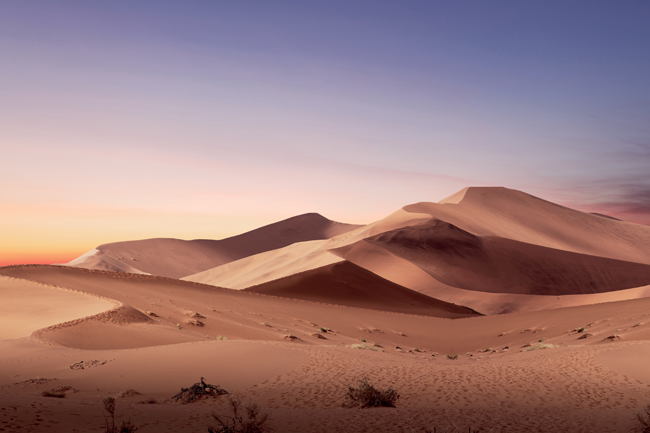

Tourism is also vitally important as a source of revenue. The harsh terrain and semi-arid climate has created a series of famed tourist attractions such as the Skeleton Coast, scene of many shipwrecks, and Sossusvlei, renowned for its red sand dunes. Wild game is also plentiful in the north of the country.

Its abundant minerals, rich oceans and spectacular scenery should be harnessed, according to the African Development Bank. ‘These natural resources offer the country a unique opportunity to expand its tourism, fish and agro-processing, and secondary industries through the further exploration of mineral beneficiation,’ it said in a report.

‘The government is aware of the need to implement the right measures, including policies to reduce the high cost of doing business, removing various bottlenecks in infrastructure, and investing in skills to exploit these opportunities for the country’s economic transformation.’

An indication, perhaps, of Namibia’s transformation was witnessed in November last year when it held the continent’s first fully electronic election. An eloquent testament to just how far the country has come as a modern nation.

By John Rossouw

Image: Gallo/GettyImages