Farming is all about watching… Watching the soil, making sure it’s well hydrated; watching the crops, checking for weeds and parasites; and watching the sky, repeating the age-old adage: ‘Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning. Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight.’ But what if there were something up in the sky, doing that watching for us?

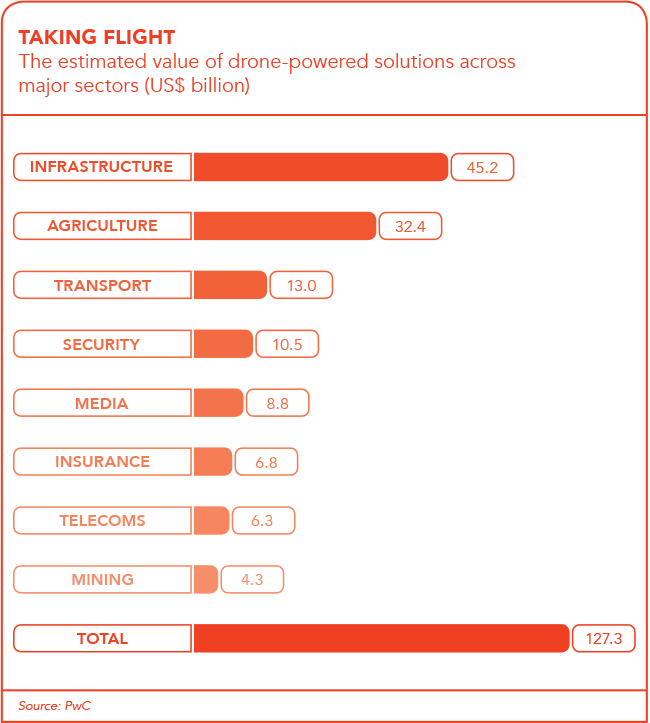

In May, PwC released a report titled Clarity From Above, which looks at exactly that: the commercial application of drones – the global farmer’s latest, high-tech eye in the sky. The report outlines how, traditionally, the main obstacle in farming has been ‘the large area of farmed land and low efficiency in crop monitoring’ – a problem exacerbated by increasingly unpredictable weather conditions that increase farming risk and field maintenance costs.

‘Until recently, the most advanced form of monitoring used satellite imagery,’ the report explains. ‘The main limitation was that images had to be ordered in advance, could be taken only once a day and were not very precise. In addition, the services were extremely expensive and gave no guarantee of quality, which could easily drop on a cloudy day.’

Unmanned aircraft systems – or drones – offer an efficient and affordable solution. As the PwC report states: ‘Today, drone technology offers a large variety of crop monitoring possibilities at a lower cost.

‘Furthermore, drones can be integrated at every stage of the crop lifecycle, from soil analysis and seed planting to choosing the right moment for harvesting.’

The unmanned aspect is key here. While light or radio-controlled aircraft need to be piloted, drones have autonomous flight capability. The software plots the flight path and controls the on-board camera, with autopilot taking the drone all the way from take-off to landing. And, crucially, a drone can survey the farm any time – or all the time.

Chris Anderson, former editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, now runs a drone company in the US called DIY Drones. Writing in MIT’s Technology Review in 2014, Anderson highlighted the advantage of the low-altitude view offered by unmanned aircraft. ‘[It] gives a perspective that farmers have rarely had before,’ he wrote.

‘Compared with satellite imagery, it’s much cheaper and offers higher resolution. Because it’s taken under the clouds, it’s unobstructed and available anytime. It’s also much cheaper than crop imaging with a manned aircraft, which can run [at] US$1 000 an hour. Farmers can buy the drones outright for less than US$1 000 each.’

Andre Laubscher, sales executive at South African drone manufacturers SteadiDrone, concurs. ‘We find that drones provide an excellent platform to mount multi-spectral and various other sensors on to enable farmers to have an aerial perspective of their land and crops,’ he says. ‘These sensors capture images in different light spectrums and provide precision agriculturalists the information they need to do an in-depth analysis of the ground and crops that were scanned.

‘The health of the farm can then be determined from this data, and decisions can be made based on this information to improve future harvests and ground preparations for these harvests.

‘The use of drones makes it easier for farmers to have accurate and up-to-date imagery at their disposal, rather than depending on outdated and irrelevant information regarding their farms.’

There’s a term Laubscher drops into the conversation – ‘precision agriculturalists’ – that lies at the heart of what makes drones so valuable to farmers. These unmanned flying machines provide a previously unimaginable level of data, giving farmers accurate, real-time readings on soil hydration, pest control, crop health and so on.

‘The implications can’t be stressed enough,’ wrote Anderson. ‘We expect 9.6 billion people to call Earth home by 2050. All of them need to be fed. Farming is an input-output problem. If we can reduce the inputs – water and pesticides – and maintain the same output, we will be overcoming a central challenge.’

Data is central to that solution. ‘One challenge that a farmer would face is determining a way to maximise the yield on a crop,’ according to Laubscher.

‘For them to do that, the farmer would need information at their disposal telling them where the most fertile soil is; where the best hydration is; what the temperature variances are in their field… And they would then be able to make informed strategic decisions to get the maximum yield out of a crop.

‘By using a drone with a sensor attached, the farmer would firstly be able to gather the data much faster and at a reduced cost, and they would then be able to make those educated decisions based on acquired data.

‘With effective crop management, the farmer would have reduced overheads and less wastage. And with increased yields, their profits would increase exponentially.’

Without saying it directly, Laubscher highlights one of the biggest attractions of agricultural drones, namely their sky-high return on investment (ROI). The American Farm Bureau Federation estimates that farmers in the US could see a ROI on agricultural drones of US$12 per acre of corn, and US$2.60 and US$2.30 per acre of soya beans and wheat.

One of the reasons for this is that – depending on the sensors and cameras attached to the machine – one drone can have several applications around a farm. ‘Apart from precision agriculture, there’s growing interest in using drones as crop-spraying aircraft instead of a full-scale fixed-wing craft and pilot,’ says Laubscher.

‘Although there are limitations to the weight loads drones can carry, they do bring the benefit of more targeted and precise spraying and pest control. Infestations in parts of a crop can be controlled more precisely, quicker and easier, meaning reduced pesticide exposure to the crop and also reduced pesticide costs.

‘In addition to this, drones could be used as a geomapping tool if the farmer wants their farm mapped, and the drone could also be used in farm safety and security. It can do fence line patrols and also be deployed when there are incidents that threaten the farm’s safety and security.’

While drones have – for better or worse – become synonymous with military strikes, spectacular aerial videos and hobbyists, several analysts are now seeing their application in the agricultural sector. The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) estimates that farms will eventually account for an 80% share of the commercial drone market.

Meanwhile, the 2015 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research report found that the agricultural robot market in the US alone is expected to grow from US$817 million in 2013 to US$16.3 billion by 2020. The report foresees robots and drones replacing people as the main workhorses on US farms.

‘People in the US and EU no longer want to work on farms due to factors such as low farm incomes, its lack of reliability and seasonal nature, and its demanding and risky nature,’ the report states. ‘Today, less than 1% of the US population claims farming as an occupation – with the average number of US farmworkers having declined from 3.4 million last century to 1 million today.’

This, however, won’t necessarily be a zero-sum game. A 2013 AUVSI report found that in the first three years of integration, agricultural robots would create in excess of 70 000 jobs, with an economic impact of more than US$13.6 billion. What’s more, according to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch report, the drone market has the potential to create an extra 100 000 jobs in the US, in turn generating US$82 billion in economic activity between 2015 and 2025.

In Africa, drone sales haven’t yet taken up, Laubscher admits. ‘Most of our sales are outside the African continent,’ he says. ‘Queries for drones in precision agriculture from South Africa are still minimal, and queries for drones further in Africa stem more from companies within South Africa that are looking to expand into the continent, rather than from farmers in Africa itself.’

The AUVSI report, however, along with the other data we’ve seen, may soon change that. The cost-saving promise will come as good news to African farmers, while the promise of job creation will surely encourage the continent’s many farm workers. After all, Africa remains, in many ways, an agricultural continent.

According to the World Bank, the agricultural sector contributes 32% to Africa’s GDP, providing employment to 65% of the continent’s labour force. In fact, as a recent KPMG report states: ‘In many countries in Africa, up to 85% of the workforce is employed in the agricultural sector.

‘Furthermore, an estimated 38% of Africa’s working youth is presently employed in the agricultural sector.’ They’ll all be watching the skies.

By Mark van Dijk

Image: Gallo/Getty Images