In many areas, including the uptake of mechanisation, access to digital technologies and the availability and use of improved seed, Africa’s farmers lag far behind the rest of the world.

In fact, according to the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), which is active in 13 countries in East, Southern and West Africa, the agricultural sector of sub-Saharan Africa is the least mechanised in the world, and farmers here have on average a tenth of the mechanised tools of their peers in other developing regions.

The AATF runs a number of projects aimed at addressing challenges hindering efficiency gains in key African staples such as maize, rice, cassava, cowpeas, bananas and potatoes. In a report on mechanisation and digital agriculture, the AATF states that the lack of mechanisation ‘has undermined the competitiveness of African farmers, reducing their productivity and exacerbating a vicious cycle where they are unable to invest in modern machinery and in digital technology that they need’.

To illustrate the gains that can be achieved from improving the way in which crops are produced by Africa’s predominantly small-holder farming sector, the AATF refers to its Cassava Mechanisation and Agroprocessing Project (CAMAP), which aims to increase the operational efficiency and improve market linkages for smallholder farmers in Nigeria, Uganda and Zambia.

Farmers in sub-Saharan Africa achieve yields of roughly eight tons per hectare on average, which is about a third of that produced by their Asian and Latin American counterparts. By making use of mechanisation, the farmers who participated in the CAMAP cassava initiative achieved average yield increases of more than 25 tons.

In 2000 the tractors in use in sub-Saharan Africa were concentrated in a small number of countries, with 70% being in South Africa and Nigeria, according to a report on sustainable agricultural mechanisation in Africa, published last year by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the AU Commission.

If South Africa is excluded, primary land preparation in Africa relies entirely on manual labour on an estimated 80% of the cultivated land. Compare this with Asia where, at that time, land preparation was performed by tractors on more than 60% of the cultivated land. However, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that farm-level mechanisation is increasing slowly but surely across Africa.

Divan van der Westhuizen, manager of the farm and inputs division at the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy, University of Pretoria, writes in a summary report following the 6th African Conference of Agricultural Economists in Abuja, Nigeria in September 2019, that after decades of persistently low use of agricultural mechanisation, the proportion of African farmers using tractors has increased since roughly 2005. He notes there is mounting evidence that, contrary to popular opinion, tractor usage is no longer mainly confined to large-scale commercial farms.

Van der Westhuizen writes, however, that given the existing structure of land size distribution, ‘increased tractor use was not as a result of tractor ownership’ but rather ‘the development of tractor rental markets’.

Cost has always been one of the main impeding factors barring small-scale farmers from accessing mechanisation. However, as Van der Westhuizen points out, the development of larger-scale farming business in African countries, might in fact hold some benefit for smallholder farmers.

Larger farmers who own tractors, he writes, could use any downtime to rent out tractor services to smallholder farmers in nearby communities if the rental costs per hectare are competitive with manual or animal traction-based land preparation. In a 2019 Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) report, the authors note that one of the most significant developments in African agriculture over the past decade has been the emergence of improved seed supply for smallholder farmers.

The Access to Seeds Index 2019 report reveals that global companies were reaching just 47 million of the world’s 500 million smallholder farmers. That was less than 10% of smallholder farmers who have access, via these companies, to the improved seeds that offer resistance to certain diseases as well as some of the impacts of climate change, such as prolonged droughts and heatwaves.

Published by the World Benchmarking Alliance, the report evaluated the activities of the 13 leading global seed companies and found that most investment was directed at a small number of countries, mostly in South and Southeast Asia. A lack of access to improved seed stock and other new farming technologies is also the reason why crop yields across Africa are only 56% of the international average, according to the FAO. However, the answer to better access to improved seed might not lie solely with the large multinational companies.

In the AGRA report researchers state that SME seed companies have proven effective in establishing a supply-chain for agricultural inputs that can benefit small- and medium-scale farmers in Africa. AGRA estimates that sub-Saharan Africa’s annual seed requirement is more than 2 million tons, but that it’s unlikely that even 500 000 tons are being produced and sold each year.

Some African countries, the AGRA report states, still do not have a single private seed company operating within their borders. Furthermore, most of the research and development work that has been done focused on only a few crops with the result that improved varieties adapted to African conditions have still not been developed for several of the continent’s critical food crops.

A new class of local, private SME-sized seed companies are, however, uniquely suited to change that. AGRA has been directly involved in providing start-up funding and other support to several smaller seed companies in a number of African countries. The report explains that ‘most of the emerging local seed companies were small but had the advantage of being able to operate profitably on very small volumes of seed sold’. It also counted in their favour that the owners of the companies had a good understanding of the needs of their customers.

‘Small- and medium-sized seed companies operate in close proximity to smallholder farmers, and hence are able to anticipate emerging crop production trends and respond by supplying the seed of the trending crops,’ the report states. But while more farmers may have access to improved seed, this does not automatically guarantee better outcomes if farmers aren’t trained. This is why AGRA also runs an initiative called the Village-Based Advisors (VBAs) model.

According to AGRA, VBAs are trained in partnership with seed and fertiliser companies on how to increase farmers’ knowledge of the proper use of agricultural inputs – such as the appropriate crop varieties, correct spacing of seeds, placement of fertiliser, and other good agricultural practices.

UPL, the fifth-largest agrochemical post-patent company in the world, recently signed an agreement with AGRA to work with the organisation to strengthen ‘last-mile service delivery’ to smallholder farmers. This, says UPL, will be achieved by helping farmers to access extension support through a further roll-out of the VBAs model. Jai Shroff, UPL Global CEO, says that his company will use its network of country outlets to distribute hybrids, crop-protection solutions and other technologies to be tried and tested by small-holder farmers in order to increase their productivity and incomes.

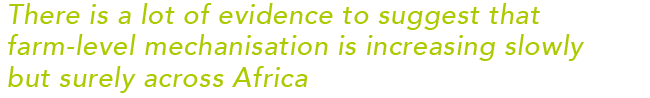

To a certain extent, gaining access to improved seed and mechanisation already represents what was only the initial phases of the technology revolution in agriculture. The next phase is the digital revolution. As AGRA’s report indicates, to be able to increase agricultural productivity in a sustainable way it is necessary for farmers to ‘move towards precision agriculture; to manage risks more effectively; and to share information fast’. Access to digital technology can result in higher crop yields and improved profitability thanks to fast and quality access to market and weather reports, for example. But to access the benefits that digital technologies offer farmers, they have to be connected to the internet.

According to AGRA, sub-Saharan Africa continues to have limited access to broadband networks that provide internet and data, with internet penetration of less than 10%. Bridging this connectivity gap will require major public and private investment, and AGRA also suggests poor, rural households should be provided with subsidies to ensure that they can access digital services at no higher cost than people living in urban areas.

With a fast-growing and rapidly urbanising population, countries on the continent need to make swifter progress in enabling farmers to access modern farming technologies.