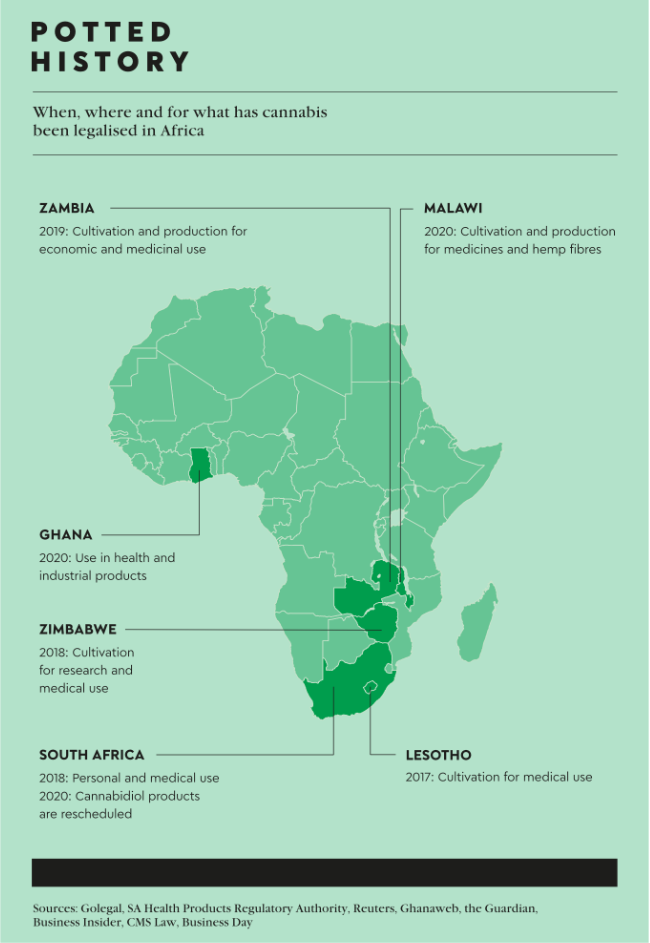

Tiny Lesotho is miles ahead of its much larger African peers when it comes to commercialising cannabis – the wonder plant that can be used for anything from health food supplements and medication to cosmetics, animal feed, textiles, green building materials, biofuel and, yes, also to get ‘high’. It was the mountain kingdom that moved quickly and became the first African nation to license the cultivation of medicinal cannabis in 2017 (followed in 2018 by Zimbabwe).

For years known only as a narcotic, canna bis is breaking into mainstream markets, such as big pharma, where medications based on cannabinoids have undergone full clinical trials and are officially licensed. It’s also disrupting the wellness and even pet-care industries. However, most African nations still need to legalise cannabis (aka dagga, weed, dope, pot or marijuana) to cash in on an industry with great economic promise, not only in the cultivation of cannabis but also in adding value by processing and manufacturing cannabis products for domestic and export markets.

Africa’s abundant land, low-cost work force and sunny climate lend themselves to growing high-potency cannabis, according to specialist consultancy Prohibition Partners. Its African Cannabis report estimates that the continent’s legal cannabis industry could be worth more than US$7.1 billion by 2023, with South Africa and Nigeria potentially developing the largest markets. In South Africa alone, the cannabis industry is currently valued at ZAR28 million and could create 25 000 new jobs, according to government figures.

The young company MG Health operates its cultivation and modern processing facilities at 2 000m above sea level. It says its operations are designed in line with the EU’s Good Manufacturing Practice, ‘including filtration, pressurisation, dehumidification, temperature control and process flow controls, while natural prevention techniques are used for the control of mould, mildew and mites’. The stringent protocols also require full trace ability (almost like the Kimberley Process against conflict diamonds) from seed to the final product, such as the exported cannabis flower, oil and extracts that are categorised as active pharmaceutical ingredients.

While every single part of the cannabis sativa plant could theoretically be commercialised in Africa, the flowers and leaves are the most lucrative as they’re used for both medicine extraction and ‘responsible adult use’. For the pharma value chain, specific strains of high-potency cannabis are cultivated under controlled indoor conditions, often in greenhouses, and with continuous quality assessments. In contrast, the agricultural cannabis grown primarily for industrial purposes is called hemp and planted outdoors in fields. South Africa’s regulators mandate fencing around any cannabis field, which insiders say goes against global industry practice, because it’s costly for growers and not necessary (hemp doesn’t typically get stolen as it doesn’t get you high). Hemp is grown for fibre and for CBD (cannabidiol), which is extracted as a food supplement and to ease chronic pain, anxiety and insomnia. But it only contains minuscule amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which has the intoxicating effect for recreational purposes and to medicate patients suffering from Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, severe nausea caused by cancer treatment and many other conditions.

While medical cannabis licence holders can cultivate plants with a high THC concentration, the permits for hemp products stipulate a THC limit. In the EU and US, this must not exceed 0.3% of the dry weight. ‘In South Africa the hemp side of the industry is constrained to 0.2%, which is incredibly low,’ says Leslie Zetler, CEO of Felbridge, a South African cultivator and supplier of cannabis and hemp-starting materials. In June 2021, the Western Cape-based company exported the country’s first commercial shipment of dry cannabis flower to Switzerland. Felbridge previously also exported in-vitro cannabis tissue to Europe and supplies South African licensed cultivators with seed, rooted clones and tissue culture.

‘It’s very difficult, nearly impossible, to grow cannabis plants with only 0.2% THC,’ says Zetler, referring to the fact that Africa’s naturally high UV light raises the THC concentration in cannabis. ‘To put this into perspective, the THC limit in countries such as Switzerland [and Malawi] is 1%, which opens up the cannabis sector for commercial opportunities such as fibre, biofuels, animal feed, and even as a protein source,’ says Zetler, explaining how a Swiss company has used genetic breeding to develop cannabis varieties that are higher in protein than soya, which enables farmers to feed more people per acre than through conventional crops.

South Africa’s regulatory framework has been criticised for stifling the fledgling cannabis industry by being overly bureaucratic and insisting on onerous and costly reporting requirements. The emphasis on traceability means that permits are tied to a specific location and individual, and are non-transferable. Any cannabis-plant material leaving the licensed premises must be documented and accounted for, according to the country’s draft Cannabis Master Plan.

The continent’s first-mover, Lesotho, can teach South Africa and other African countries a lesson with its legislative frame work, says Liëtte van Schalkwyk, associate at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s dispute resolution practice. ‘Lesotho created an enabling environment with the purpose to attract investors while also promoting the local labour market. South African authorities want to create the perfect, controlled environment for the cannabis sector, but we need to get things moving and require basic regulations to kick-start the “green gold” industry.

‘South Africa should promulgate “one size-fits-all” legislation with a strict set of regulations that can be amended from time to time, not only to fit the needs of the industry but also to grow with the industry. The legislation doesn’t have to be perfect at this stage, the authorities just need to put pen to paper,’ says Van Schalkwyk.

Regulatory certainty would assist businesses such as JSE-listed Labat Africa, which repositioned itself in 2019 to become a fully integrated cannabis healthcare company. The business model is based on a value chain from cannabis seed to the sale of active pharmaceutical ingredients, as well as the supply and distribution of finished dose form for the complementary medicines industry. Labat has been acquiring cannabis companies, including Ace Genetics (a Western Cape-based cannabis genetics company) as well as majority stakes in Leaf Botanicals (a cannabis cultivation company in the Northern Cape) and Knuckle Genetics (a seed and genetics business that produces high-potency cannabis flower, oil and concentrate for export). Labat also has an exclusive distribution agreement for premium grade ‘CBD smokable’ with US-based company Ace and Axle.

In December, Labat announced it had secured a ZAR300 million cash investment from a US firm. ‘We expect that the funding will enable the business to successfully navigate tough South African trading conditions and secure a prime spot for the business in the growing cannabis sector,’ says Herschel Maasdorp, Labat Healthcare Group executive.

‘The funding enables the company, while it continues to maintain focus on strict cost controls, to tailor the timing and size of each capital call to support its ongoing research through clinical trials, its growth, customer engagements, operating costs and planned manufacturing, as well as the export of medicinal cannabis into the European market, while safeguarding shareholder value.’ While Labat made a secondary listing on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange at the end of 2021, another South African cannabis company – Cilo Cybin – is planning to list on the JSE in early 2022, with a possible dual listing in Luxembourg or another European stock exchange. ‘Our aim is to raise ZAR500 million by way of an initial public offering [IPO],’ says CEO Gabriel Theron in an investor update. ‘The intent of the IPO is to establish Cilo Cybin as a global player to deliver a holistic and individualised solution that enables our customers insights into their wellness, performance, and longevity.’

The company’s first non-scheduled CBD product range was recently launched online, focusing on ‘sleep, relax, energy, pain’. Cilo Cybin is the first company in South Africa with licences to cultivate, process and pack medical cannabis, and is now considering expanding into ‘magic’ mushrooms.

‘Globally, psychedelics are making significant inroads as an industry, which I believe will be bigger than cannabis,’ says Theron. ‘[We have] applied for a research permit to explore the uses of the magic mushroom chemical, psilocybin, used for anti-depressants, post-traumatic stress and anxiety.’

But that’s a different story. Above any thing else, African nations need to establish enabling legislative frameworks – like that of Lesotho – to get the legal cannabis sector up and running and make the most of the continent’s climatic advantage and other favourable aspects.