It sounds like the plot to one of those TV shows you’d stream on your phone… This past June, a group of Irish and American hackers calling themselves the Community were caught stealing more than US$2.4 million in cryptocurrency, in an international scam that involved switching (or porting) mobile phone numbers from one SIM card to another. By trickery and skulduggery, they got password reset links via text message for a variety of accounts tied to the hijacked phone numbers, and the victims who were having their digital pockets picked didn’t even know it was happening.

The concept behind SIM-swap fraud is frighteningly simple. A cybercriminal will contact your mobile carrier and convince them – using either bribery or trickery – to switch your phone number over to their SIM card. Most carriers usually only ask for basic information, such as your phone number, name and birthday; and it’s not hard for criminals to access those details from your email signature or social media profile. Since a phone number can work on only one SIM card at a time, while all of this is happening your phone will register ‘No Service’, so you’ll think the network is down. You’ll still be able to access WiFi, so your emails and WhatsApp messages will come through as normal. Meanwhile, the hacker will receive your incoming calls and text messages, letting them access – and clean out – your bank account.

It’s a fairly easy and lucrative scam, and it’s happening more and more. South African bank Absa recently had to refund one of its clients ZAR3.1 million that was stolen from his account as a result of SIM swapping. Over in the US, meanwhile, cryptocurrency-investor law firm Silver Miller filed claims against mobile carriers AT&T and T-Mobile last year on behalf of clients who’d been robbed of US$400 000 and US$250 000 through SIM-swap fraud.

A report by the South African Banking Risk Information Centre (SABRIC) found that mobile banking cybercrime in the country almost doubled in 2018. ‘Cybercriminals employ increasingly sophisticated methods to use the victim’s number to do a SIM swap, download banking apps and illegally conduct transactions,’ SABRIC CEO Kaylani Pillay said at the launch of the report. ‘If reception on your cellphone is lost, immediately check what the problem could be, as you could have been a victim of an illegal SIM swap on your number. Also, regularly verify whether the details received from cellphone notifications are correct and according to the recent activity on your account. Should any detail appear suspicious, immediately contact your bank and report all log-on notifications that are unknown to you.’

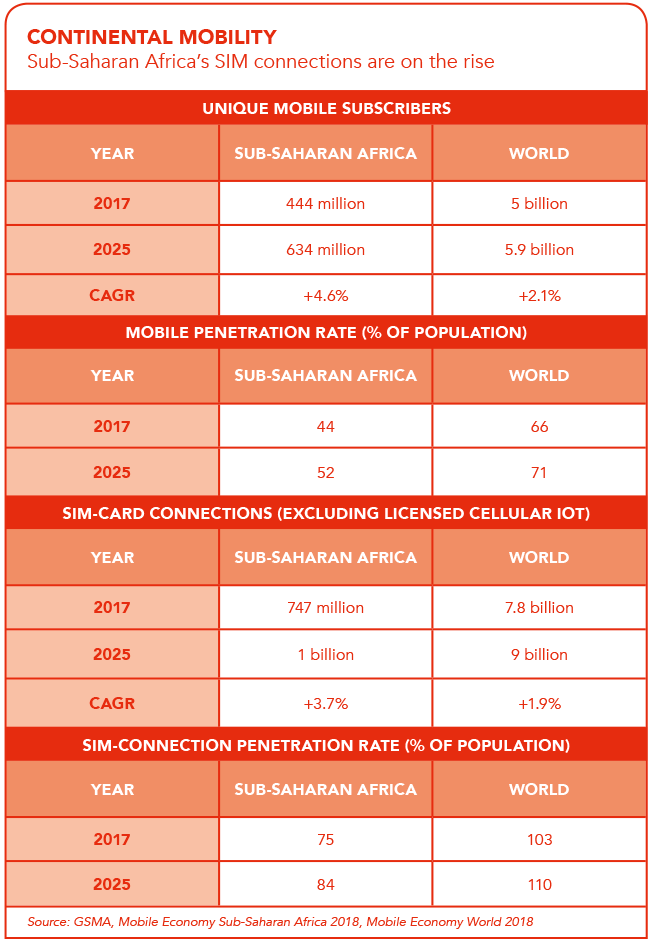

That’s easier said than done – especially in a region such as sub-Saharan Africa, where mobile payments are so common. In Kenya for example, central bank data shows that mobile money transactions accounted for KES3.98 trillion in 2018, at an average of KES10.92 billion in mobile cash transactions per day. The equivalent of nearly half of the country’s GDP moved through mobile phone transactions, making it a huge target for fraudsters. Given that most banks rely on one-time passwords (OTPs) or SMS confirmations, while mobile payments offer convenience and connectivity, they’re also opening the continent up to a wave of SIM-swap fraud attacks.

Fabio Assolini, senior security researcher at Kaspersky Lab, outlined the implications during the company’s recent Cyber Security Weekend in Cape Town, and in a follow-up report. ‘Despite financial inclusion services prospering, the flip side to this is that it opens up a world of opportunities to cybercriminals and fraudsters who are using the convenience a mobile phone offers to exploit and poke holes in two-factor authentication processes,’ said Assolini. ‘The population’s technological literacy is very low, especially those on lower incomes. Remarkably, many of the fraudsters are prisoners who somehow have access to mobile phones and a lot of spare time on their hands.’

He added that fraud using SIM swap is becoming common in Africa and the Middle East, affecting countries such as South Africa, Turkey and UAE. ‘Countries like Mozambique have experienced this first-hand,’ he writes. ‘The implemented solution, by banks and mobile operators in Mozambique, as a result, is something I believe we must learn from and encourage other regions to investigate and apply, among other aspects, to mobile payment methods of the future – as a way to ensure that mobile phones do not become an enemy in our pockets.’

Assolini said that the amounts lost in attacks vary by country, but that ‘on average fraudsters can steal US$2 500 to US$3 000 per victim, while the cost to perform the SIM swap starts with US$10 to US$40.’ While this is obviously a threat to individuals, are Africa’s businesses also experiencing the same types of cyberattacks? ‘Not yet,’ says Graham Croock, director of IT audit and risk at financial services company BDO South Africa. ‘SIM-swap fraud is identity theft, and the reason it’s growing is because the fraudsters are starting to target cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency hasn’t yet matured, which is why I say “not yet”.’

Croock warns that the bring-your-own-device (BYOD) phenomenon, where employees use their personal smartphones for business use (and vice versa), makes it even easier for fraudsters to access both personal and company bank accounts. ‘Then you’re really able to monetise it,’ he says. ‘And when you add in access to crypto, when the currency matures and becomes more widely used, it means that a SIM swap will make you able to walk into any shopping mall with someone else’s banking information. Then it becomes like having a blank cheque.’ The risk will increase as the cryptocurrency market develops, says Croock. ‘Blockchain is going to be the future,’ he says. ‘And this kind of crime is just going to grow.’

It’s not all bad news, though. The solution from Mozambique that Assolini mentioned is already being hailed as a model for other countries to follow. Smartphones are not widespread in Mozambique, where most people use feature phones and the majority of banks rely on OTPs and SMS. That’s fertile ground for SIM-swap fraud – and the problem got so bad that rumours started doing the rounds that banks and mobile carriers were colluding with cybercriminals in the scams.

To solve the problem (and salvage their reputations), Mozambique’s banks and mobile companies worked together to create a surprisingly simple solution. ‘All mobile operators in Mozambique made a platform available to the banks on a private API [application programming interface, or communication software] that flags if there was a SIM swap involving a specific mobile number associated with a bank account over a predefined period. The bank then decides what to do next,’ said Assolini. ‘Most banks block any transaction from a mobile number that has undergone a SIM card change within the last 48 hours, while others opt for 72 hours. This period of 48 to 72 hours is considered a safe period during which the subscriber will contact their operator if they have fallen victim to an unauthorised SIM card change.’ (If the mobile phone owner has legitimately changed their SIM card, there’s a process where the customer would go to the bank’s local branch office for in-person, face-to-face identity verification. It’s a small inconvenience when seen against the bigger picture.)

Assolini said that Mozambique saw an immediate decrease in SIM-swap fraud after its biggest bank adopted this solution. The country’s central bank is now considering making it mandatory. That will go some way to making bank account holders and mobile phone users feel safer, while staying a step ahead of the cybercriminals. After all, as Assolini told delegates at the Cyber Security Weekend: ‘Your phone is no longer just a phone. It is your wallet. This situation may be convenient for you and me, but it is also one that is extremely attractive to cybercriminals.’